Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

21 Feb, 2023

| World traders have turned away from the Moscow-based economy in favor of trade with other suppliers of metals and mines as experts expect permanent changes to how the world thinks about its supply chains. Source: Elena Liseykina/Moment via Getty Images |

One year after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, metals and mining trade flows have shifted as countries look to regionalize supply chains for crucial raw materials due to aversions to purchases that could support the Kremlin.

|

The start of the war in late February 2022 sent the price of many commodities skyrocketing, but buyers have adjusted after much of the world opted to bench Russian metal suppliers. However, Russian commodities are moving despite countries looking elsewhere for supplies, including by increasing domestic sourcing of crucial materials.

"The Russians found a way to sell, and the rest of the world found a way to buy," Rick Rule, veteran mining sector investor and former president and CEO of Sprott U.S. Holdings Inc., told S&P Global Commodity Insights. "As always, while markets are messy, they work. The immediate cure for high prices was, of course, high prices."

Market dislocation

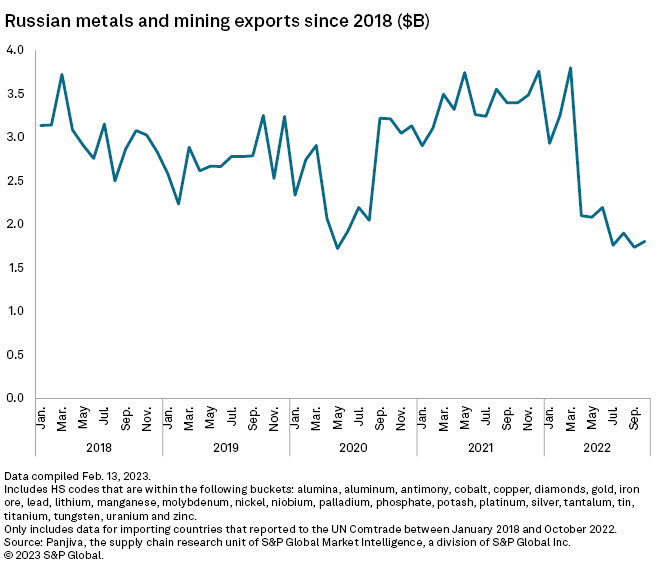

After the start of the invasion, the value of Russian exports of cobalt, copper, diamonds, iron ore, gold and other selected metals and mining products dropped 35.5% between February and April 2022, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. Since that steep decline, the cumulative value of those exported goods has held relatively steady. However, the total value of the same materials remained down 46.9% year over year in October 2022, based on the most recent available data.

"Despite political sanctions from the West, what you learn over time is that countries don't have friends: Their leaders and their elites have interests," Rule said. "The Russian material will find its way into the market."

The invasion has disrupted markets for mining products, natural gas and oil, but the changes have been less dramatic than many first suspected. For example, Europe adapted by importing liquefied natural gas from the U.S. and making other adjustments.

"I'm surprised by how well the global commodity markets have done over the past year when you think about the prominence of Russia for many different commodities," said Mark Ferguson, Commodity Insights' director of research for metals and mining.

Even as traders sought to avoid some Russian products, the world has been selective. While Russian oil has struggled to find markets, titanium, nickel and aluminum have all avoided U.S. sanctions, as Russia is a crucial supplier, and imposing tariffs would create problems for multiple markets.

"It shows that in times of war, the things that we thought were impossible, either from a bureaucratic, political, or economic perspective, are not impossible," Bazilian said. "People are resilient, and societies and economies are terribly innovative when they really have to be."

With many economies pivoting away from the Kremlin, Russia has increased its trade with other countries, such as Germany. However, Ferguson said Russia is selling those metals at lower prices. Of the metals products analyzed by Market Intelligence, China had a 47.6% market share of the value of Russian exports in the first three quarters of 2021, decreasing to 36.8% for the comparable 2022 period. Germany increased its market share for the same metals from 16.6% to 24.4% over the same period.

No end in sight

With no imminent end to the war, it could be a long time before world markets again embrace Russian supplies. Russia would likely need to end the conflict and assist in compensating Ukraine for damages before it can reassume its former trade roles, said Konstantin Sonin, a Russian expatriate and professor of economics and public policy at the University of Chicago.

Russia will have to recover as well. Hundreds of thousands of people are pouring out of the country, a reminder that many are not supportive of the war, Sonin said.

"There has been a massive drop in the quality of living," Sonin said. "What could be more evidence that the people are extremely unhappy?"

Regionalizing supplies

In response to the conflict, many world leaders shifted from the belief that keeping Russia strongly tied to the energy trade would prevent the country from undertaking aggressive military tactics, Bazilian said. Many also mistakenly viewed Russia as little more than "a gas station," Bazilian said, when the country is also a major world player in various other markets, including nickel and steel. Those products and similar ones fuel the energy transition, consumer goods and critical military supply chains around the globe.

Now, instead of globalizing world supply chains, a lot of countries and companies are more apt to think in terms of regionalizing supply.

"When you think about policy instruments such as the Inflation Reduction Act, it's definitely incentivizing various countries, particularly Western economies, to develop more secure supply chains for the materials they need and to effectively divorce themselves from various Russian commodities," Ferguson said. "The world has done pretty well to move off [Russian] gas and oil. It's a little bit harder to peg on things like nickel and the [platinum group metals], but I certainly think it has stimulated interest in companies looking elsewhere for their supply."

Prices have stabilized

Much of the high pricing currently seen in metals markets is the result of increased demand related to the energy transition, Ferguson said. If the war ended today, commodity prices would not adjust dramatically, said Keith Hartley, CEO of LevaData, an AI-based supply management platform for direct material sourcing.

"It takes time for these supply chains to sort of flex back to equilibrium in the supply-demand curve," Hartley said. "There's going to be an ongoing sort of skepticism about sourcing parts and ingredients from Russia. The executives for manufacturers that I spend time with have never been more serious about nearshoring than they are right now."

However, the disruption could also breed permanent changes beyond supply chain flows. For example, a manufacturer depending on Russian palladium for a particular motherboard might be able to innovate and use alternative materials sourced from elsewhere, Hartley said. Automakers have already started using more platinum in the face of high palladium prices. Hartley predicted the war would kick off an expansion of funding into material science research.

"If a manufacturer is not proactively looking at their commodities, their ingredients and their parts, they are behind," Hartley said. "The more resilient and the more agile companies can be with their supply chain, the better for us all."

Another looming supply issue may take some time to materialize. Strains on the Russian economy and the diversion of cash from extractive industries to the war effort are likely to result in Russian underinvestment in mining and oil businesses, similar to what occurred with the oil industry in Venezuela, Rule said. And that could have implications for the country's ability to maintain or increase the production of metals.

"That will lead, in the out years, to them having difficulty producing," Rule said. "People forget, particularly people interested in geopolitics and stuff, that these are really capital-intensive businesses."

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.

Panjiva is the supply chain research unit of S&P Global Market Intelligence, a division of S&P Global Inc.

Evaluate the impact of the Russia-Ukraine conflict on the metals market with our essential mining intelligence. Learn more >