Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jun 22, 2018

One step forward, two steps back for Polish pension reform

- Since the global financial crisis, Poland has stepped backward in preparations for an aging population, most recently with last year's reduction of the retirement age.

- Plans for a new employee pension program could represent a step forward, but the launch has been delayed amid intra-governmental conflicts.

- With all the changes in Poland's pension system in recent years, the government will have to work to restore public trust in the pension system and boost investor confidence.

In 1999, Poland was the second country in Central and Eastern Europe (after Hungary) to introduce a three-pillar pension system, shifting from the previous pay-as-you-go system. Since the global financial crisis, however, the system has been gradually dismantled, and the vast majority of Poles have switched back to the old system. Although the government has discussed a complete shutdown of the second pillar of personal accounts and a shift toward a new employee pension program, those moves have been delayed.

Retirement age reduction brings a range of

challenges

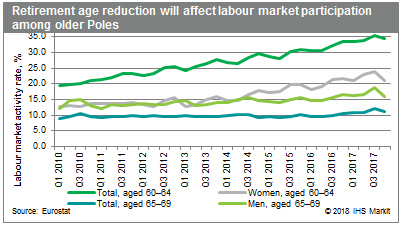

While the 2011-15 cabinet tried to reduce pressures to the

pension system by raising the retirement age, the 2015-19

government reversed those changes in October in an effort to appeal

to older voters. The retirement age is now back at 65 for men and

60 for women, versus 67 for both genders under the previous plan.

That step threatens to destabilize the pension system, raise fiscal

and poverty risks (especially among women), and further hinder

labor availability. A 2017 study published by the European

Commission projects that the retirement age reduction will diminish

Poland's per-capita GDP by 7% compared with the baseline scenario,

based primarily on the reduced labor supply. The study also

indicates that a substantial fiscal adjustment will be required to

finance the rising pension expenditures.

Initial data indicate that the vast majority of Poles who were eligible to retire thanks to the age reduction have chosen to do so. The ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party has also proposed several key social programs directed at the elderly population. Following up on the 2016 Family 500+ child support program (aimed at raising Poland's weak birth rate), the government plans to implement a 500+ program for pensioners, starting as early as end-2018. This would provide pensioners with an annual payment around Christmas time, ostensibly to enable seniors to make small investments, such as renovations or purchases of new appliances. The payments are intended to help compensate for the fact that many Poles who are taking advantage of the retirement age reduction will receive very small pensions, threatening to erode popular support for the PiS among the elderly population. In another measure, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki announced plans in April to launch an Accessibility Plus (Dostępność+) program to improve living conditions for seniors and the disabled by easing access to public transport and public buildings.

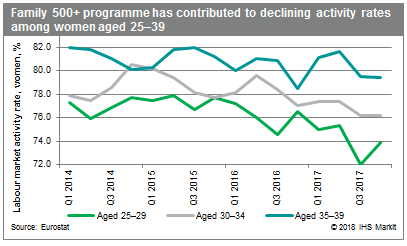

On the labor front, the total working age population in the 15-64 age category has been falling steadily since 2010, partly due to emigration. Many businesses in Poland are struggling to find workers, as unemployment rates drop to historic lows. Shortages are especially severe in the construction sector, which needs workers to contribute to key European Union-funded infrastructure projects through to 2020. Wage pressures have been high in many sectors. Under these circumstances, government policy should be geared towards encouraging increased labor force participation, but instead the cabinet has taken steps to limit the workforce among women of child-bearing age (through the 2016 Family 500+ program) and seniors (through the reduction in the retirement age).

Outlook

Poland's pension system is currently facing considerable

uncertainty. Although expert opinion on the proposed workplace

pension system has been positive, the plan may be watered down amid

criticism that it would impose too large a burden on companies,

especially those with large numbers of employees and low

profitability. The potential impact of the second-pillar

dismantling is also difficult to predict since it depends on the

shape of the final legislation. In Hungary, which dismantled its

own second-pillar program in 2010, the medium-term impact has been

softened an increase in the retirement age, although the outlook is

set to deteriorate from 2035 onward.

Regardless of the final details of the government's pension plan, the success of the program will depend largely on whether steps are taken to restore trust in the pension system and encourage employee participation. A recent poll by the money.pl site indicated that more progress is required in that regard: 70% of Poles were unaware of the government's plans for pension reform, while 42% would like to see equal pensions for all retirees.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fone-step-forward-two-steps-back-for-polish-pension-reform.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fone-step-forward-two-steps-back-for-polish-pension-reform.html&text=One+step+forward%2c+two+steps+back+for+Polish+pension+reform+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fone-step-forward-two-steps-back-for-polish-pension-reform.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=One step forward, two steps back for Polish pension reform | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fone-step-forward-two-steps-back-for-polish-pension-reform.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=One+step+forward%2c+two+steps+back+for+Polish+pension+reform+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fone-step-forward-two-steps-back-for-polish-pension-reform.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}