SUMMARY

Should investment results be attributed to skill or luck? Genuine skill is likely to persist, while luck is random and fleeting. Thus, one measure of skill is the consistency of a fund’s performance relative to its peers or to its benchmark. The Persistence Scorecard shows that regardless of asset class or style focus, active management outperformance is typically short-lived, with few funds consistently outranking their peers or benchmarks.

Recent years illustrate this point quite well. Exhibit 1 shows that the top-quartile funds of 2019 often continued to lead the way in 2020. Had these funds developed a consistent winning strategy? Sadly, no. Even with the bull market extending into 2021, these funds quickly reverted to the mean, and only 2.2% of the 2019 domestic equity winners remained in the top quartile by 2021.

If we extend the time horizon to five years, the picture looks still more bleak. Even selecting for the category with the highest observed persistence, just 3.5% of large-cap funds stayed in the top quartile each year. Mid-cap and small-cap funds displayed poorer persistence across all horizons, with no small-cap fund remaining in the top quartile for five years.

Some statistically minded readers might note that these numbers are occasionally better than what would be expected if fund performance were randomly distributed. For example, the odds that a top-quartile fund in one year could remain in the top quartile for the next four consecutive years might be calculated as (25%)4 = 0.39%, and the 3.5% referenced previously is substantially better than that. While the persistence report does not prove that fund performance is completely random, from a practical or decision-making perspective, it reinforces the notion that choosing between active funds on the basis of previous outperformance is likely a misguided strategy. After all, there remains a 96.5% chance that a top-quartile fund will not stay in the top quartile consistently for the next four years.

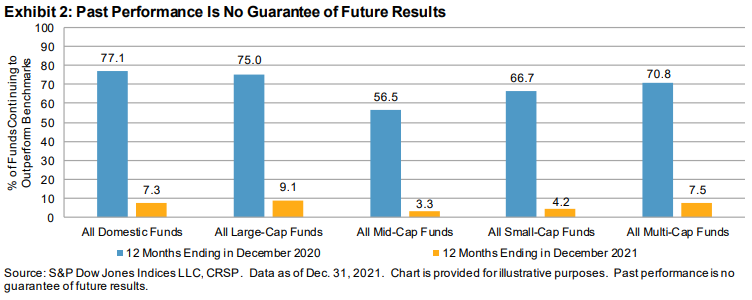

Another way of evaluating performance persistence is by comparing performance against fund benchmarks, rather than against peer groups. Any fund alpha quickly proved fleeting viewed under this lens as well. For example, out of 791 large-cap equity funds, 232 (29.33%) beat the S&P 500® in 2019. As might be expected from the previous statistics, there was significant follow-on for 2020, with 174 of those 232 (75.0%) continuing to put up positive alpha for the next year. Fast-forward to the end of 2021, and only 21 funds (9.1%) repeated their outperformance over the benchmark.

Unsurprisingly, the one pattern that did hold across equity funds was the tendency of the poorest-performing funds to close. Fourth-quartile funds were almost always the most likely to merge or liquidate over the subsequent three- and five-year windows, as 142 out of the 484 All Domestic Funds (29.3%) classed as bottom quartile from the December 2011–December 2016 period closed their doors within the next five years.

Fixed income funds showed results similar to equities, as strong one-year persistence soon reversed course. In 11 of the 13 categories considered, not a single top-quartile fund from 2017 maintained that status annually through 2021. Across all fixed income categories, a nearly identical 28.9% (63 out of 218 funds) of bottom-quartile funds from the December 2011-December 2016 period were consigned to the history books within five years.