Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Oct 07, 2020

US-China decoupling:Thinking about scenarios

The US-mainland China relationship that has underpinned globalization for decades has begun to unravel, with far-reaching consequences for business operations around the world. A dispute that centered around commercial issues of trade, investment, currency, market access, and intellectual property rights as recently as 2018 has rapidly expanded to into a broad political rivalry that encompasses geopolitical alliances, state security, and public health.

Through October our Economics & Country Risk group will be exploring two scenarios for the 'decoupling' of the world's two largest economies. A qualitative narrative rooted in country risk coverage over the last three years will be modelled in our Global Link Model (GLM) of 68 major economies and 57 industrial sectors. As with any scenario, we consider economic dependencies, pathways, and focus on which sectors are most affected to identify business impacts and indicators to monitor that give early warning of those impacts. We begin with an analysis of political drivers.

Political drivers

Trade to geopolitical rivalry

Decoupling is not new. Over the last decade China has been the more proactive 'decoupler'. The Belt & Road Initiative (first announced in 2013), the Make in China 2025 industrial policy (2015), and efforts to internationalize the renminbi (bilateral swap arrangements with Japan, South Korea, and some ASEAN countries were established in the early 2000s) can be seen as a clear-eyed mission to reduce China's dependence on the US.

But the speed and range of US actions over 2020 have made decoupling an urgent strategic issue. Just this year, the US government has, for example, blocked semi-conductor supplies to Huawei; called for divestment out of US-listed Chinese entities; sanctioned senior Chinese officials; sanctioned 24 Chinese state-owned enterprises; sent a senior official to Taiwan for the first time since 1979; and substantially increased force levels in the South China Sea. In a speech in late July, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo moved the US attitude to China from 'pro-engagement' to 'distrust and verify' - riffing on President Ronald Reagan's 'trust and verify' attitude towards the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

US resolution may alarm the Chinese government in at least two ways. First, it seems to have wide and deep bipartisan support. A Democratic administration in 2021 is likely to maintain the direction of policy even if it adopts a more consultative, multilateral approach. Second, US action has quickened the resolve of several other major economies - most clearly in China's Asia-Pacific neighborhood. On 5 June Australia announced changes to its foreign investment rules that will tighten scrutiny of foreign investments in assets categorized as 'sensitive national security business'. It followed Japan's implementation of similar new rules in May. Then in August Japan, Australia and India jointly announced a new supply chain initiative. All three items intend to reduce economic exposure to China - especially in strategically important sectors that bear on core national interests. There are examples from other regions too, for example the UK's decision to phase out Huawei from its 5G infrastructure by 2027.

Preparation for 'comprehensive escalation'

China, meanwhile, is not passive. Officially, the Chinese government frames its US policy as pro-dialogue and 'anti-decoupling', aiming to reassure a public whose confidence has been shaken. But the forthcoming Five-Year Plan is likely to emphasize a policy of 'dual circulation' that will seek to make China more economically independent. Former deputy minister of the CPC's International Liaison Department Zhou Li has said that China should prepare for a "comprehensive escalation of US-China rivalry", and that China must break away from the "US dollar hegemony" by decoupling the renminbi from the US dollar system. The People's Bank of China has accelerated its efforts to internationalize the renminbi by relaxing restrictions around cross-border trade, facilitating foreign investment, and increasingly currency convertibility. China's longer-term strategy will seek to reduce reliance on US technology too. This will include development of 'core competencies': President Xi Jinping has stressed the need to advance China's indigenous capabilities in integrated circuits, biomedicine, and artificial intelligence. Recent policies such as China Standards 2035 and New Infrastructure are in support of these development.

Qualitative to quantitative

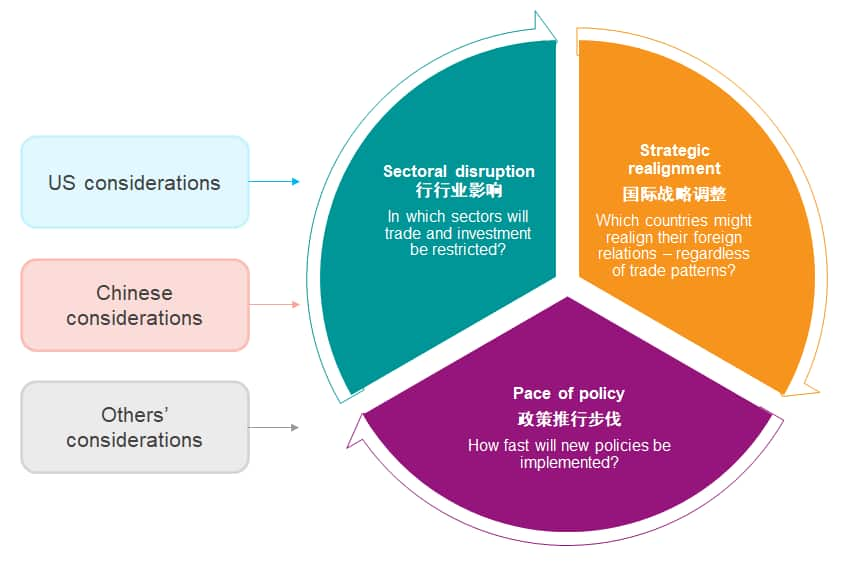

This overview of political drivers already yields three key - and quantifiable - variables that will shape our scenarios:

- Sectoral disruption

The US-China rivalry has explicitly moved beyond the narrow issue of trade to a broader strategic confrontation. That, and the actions of US allies like Japan, India, Australia and the UK, indicates the decoupling will be nuanced at the sectoral level. Policy is aimed at minimizing foreign control of critical sectors and supply chains. Sectors considered 'critical' may be recalibrated. But sectors will not be affected equally by decoupling policies. - Strategic realignment

As the world's two largest economies 'decouple', several other countries will have to balance their economic, strategic and security interests and reassess their geopolitical alignment. The points of balance can be recalibrated so that under more severe scenarios more governments opt to realign/ deepen their foreign alliances - despite their economic interests. - Pace of policy

The priorities and approach of the incoming US administration are likely to determine how fast sectoral and strategic policies are implemented. In a 'hard decoupling' scenario, the US would apply further tariffs on several Chinese goods and could cancel the Phase One Trade Agreement. The US would also consider using additional sanctions or regulatory barriers, such as enhanced reporting standards, to stop state-affiliated Chinese companies establishing dominant global market positions. In a softer, 'moderate decoupling' scenario, the US would maintain its current policy trajectory but disputes with Beijing would be addressed through existing multilateral institutions, and after consulting US allies instead of through a unilateral introduction of tariffs. In both cases, China would seek to retaliate proportionately to the US in terms of tariffs and regulatory barriers, rather than escalate, while continuing its longer-term strategy to develop 'core competencies'. The net effect would be that the implementation of decoupling policies would be slower under the second, softer scenario.

US-China decoupling

Taking into account the above and more, we will quantify two scenarios. Our starting point will be our ongoing, country-level analysis of complex geopolitical dynamics and baseline forecasts of economic and sectoral developments. We will quantify the macroeconomic impacts, including:

- How will global trade and investments be affected?

- What will be the effects, by sector, on production, employment, capital expenditure and profitability?

- How much would decoupling weigh on economic growth in Asia-Pacific, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa?

- What will be the purchasing power losses for US consumers?

- Could decoupling set the stage for a banking crisis?

- What are the ramifications for labor markets?

- Who will benefit from the trade and investment diversion - in Asia-Pacific and beyond?

- Will other countries be drawn into trade and/or currency wars?

- Which industries in which countries will gain or lose?

- How will decoupling impact China's technology advancements and long-term economic growth?

If you would like more information, or are interested in reading the report, it is available for purchase.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-china-decoupling-scenarios.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-china-decoupling-scenarios.html&text=US-China+decoupling%3aThinking+about+scenarios+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-china-decoupling-scenarios.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=US-China decoupling:Thinking about scenarios | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-china-decoupling-scenarios.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=US-China+decoupling%3aThinking+about+scenarios+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-china-decoupling-scenarios.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}