Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Aug 24, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic will hurt long-term economic growth

Crises not only plunge economies into recession in the near-to-medium term, but they can also inflict long-term damage. The oil shocks of the mid-1970s and early 1980s were a major cause of sluggish productivity growth for the following decade and a half. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09 was, in part, responsible for lower growth in total factor productivity, labor force, and business fixed investment (the determinants of potential GDP) in the 2010s. Recent estimates suggest that the actual level of potential real GDP by 2019 was 5-8% lower compared with projections that were made before the Global Financial Crisis. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may have similar impacts on the determinants of long-term economic growth.

Labor force

The labor market carnage fallout in the wake of the pandemic can only be described as massive. By some estimates, as much as one-third of job losses and one-fifth of the income losses may be permanent. Long-term labor market damage is likely to be concentrated by industry (e.g., travel and entertainment) and by demographic group (e.g., minorities and low-skilled workers). Sustained high unemployment will also lead to people dropping out of the labor force (as they did in the 2010s) and to a sustained loss in skills and productive capacity. Restrictions on immigration will further hurt labor force growth. On the plus side, the shift to work-from-home could increase labor force participation by parents with younger children.

Capital stock

The massive increase in uncertainty that has accompanied the pandemic will significantly reduce the appetite among businesses to take risks and to make investments in equipment, structures, and intellectual capital. Less investment, along with the tsunami of bankruptcies, will result in a lower capital stock than otherwise might have been. Rapidly rising corporate debt levels will also discourage capital investment. In addition, lower utilization rates of physical capital such as planes, sports facilities, and hotels will hurt the productivity of capital. On the plus side, the need to rely less on an infection-prone work force may induce companies to substitute capital for labor (e.g., by making more investments in robotics).

Total factor productivity

The overall efficiency of economies (total factor productivity) has also taken a beating since the onset of the COVID-19 virus. The decimation of global supply chains and the sharp deceleration of globalization has added to the woes of many manufacturing industries and worsened their productivity performance. While welcome in some ways, remote work has also become an obstacle for key business activities such as completing projects on time and training new workers. On the plus side, accelerated trends in digitization will improve productivity, at least in the long run.

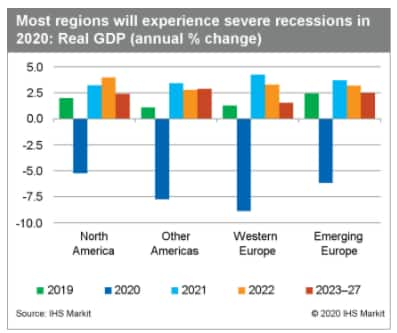

While it may be a little early to fully quantify the long-term economic impact of the pandemic, IHS Markit estimates that by 2030 the level of real GDP for key developed economies could be 2.0-5.0% lower compared with a no-pandemic scenario. In our August forecast, after a contraction of 5.1% in 2020, global real GDP is projected to expand at a 3.5% annual rate from 2020 to 2025. Growth settles to annual rates of 2.8% from 2025 to 2030 and 2.6% from 2030 to 2040.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-covid19-pandemic-will-hurt-longterm-economic-growth.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-covid19-pandemic-will-hurt-longterm-economic-growth.html&text=The+COVID-19+pandemic+will+hurt+long-term+economic+growth+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-covid19-pandemic-will-hurt-longterm-economic-growth.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=The COVID-19 pandemic will hurt long-term economic growth | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-covid19-pandemic-will-hurt-longterm-economic-growth.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=The+COVID-19+pandemic+will+hurt+long-term+economic+growth+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-covid19-pandemic-will-hurt-longterm-economic-growth.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}