Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Apr 27, 2018

Sweden maintains policy rate at April meeting

- The decision to maintain interest rates was the expected outcome of this meeting; yet immediately following the announcement the krona began a slide against the euro that took it to its lowest level since 2009 by the time trading closed on Thursday (26 April). We believe that this is because of the dovish move to shift the rate path, pushing the first hike into the future.

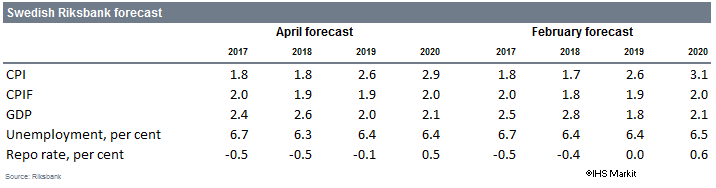

- According to the press release, rate rises will begin at the end of 2018, rather than the middle of the year as indicated after February's meeting.

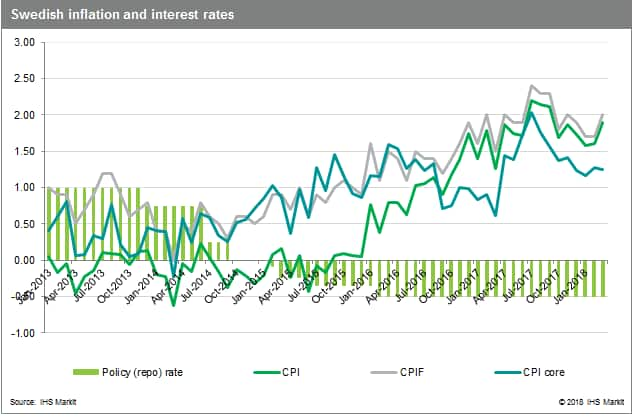

- This dovishness comes in spite of a firming of 2018 forecasts for both CPI and CPIF (inflation at fixed interest rates, the preferred Riksbank metric).

- We remain concerned that the central bank's single-minded focus on the 2% CPIF target is crowding out all over monetary policy concerns. Increasing the risk that emergent and already developed domestic pressures could become unruly.

As expected the Swedish central bank (Riksbank) committee voted to maintain the policy (repo) rate at -0.5% during its meeting on 25 April. Simultaneously the board adjusted the forward guidance pushing back the first rate rise to the end of 2018; a risky move given the warping effect that the low interest rate environment is having on the domestic economy.

It is clear from this release that the Riksbank remains firmly entrenched in its 'cautious' stance. Where this 'cautiousness' predominantly concerns inflation. It is also likely linked to the downgrade of the Riksbank's GDP estimate for 2018 to 2.6%, compared to 2.8% in the February monetary policy report. As strong economic fundamentals in the domestic economy, including robust GDP growth, and falling unemployment; have been a driving rational behind the hawks reasoning for a rate rise. This downgrade removes some rate rise pressure from the bank's calculations; allowing for an increased dovish stance.

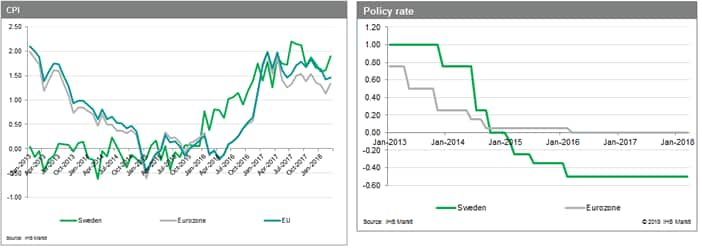

At the same time the bank underlined its continued inflation concerns noting: 'Inflation needs continued support from monetary policy . . . The risks of too low inflation merit particular attention, as at the prevailing interest rate levels this is more difficult to manage than inflation that is too high.' Concerns about the fragility of inflation are well founded; yet we think is overemphasizing the importance of the exact 2% target. Given how long it has taken for both the CPI and CPIF to recover, significant downside risks remain. There is considerable uncertainty surrounding inflation, and markets are very sensitive to inflation undershooting, as we saw earlier this month, when the March inflation numbers disappointed the market. However, given's March's 1.9% year on year (y/y) reading for the CPIF, and the six-month period in 2017 when interest rates ranged between 1.9-2.4%, it is also possible that markets are simply getting frustrated with the endless cycle of pushing back the first rate rise, when the CPIF is close enough to target. Many market commentators are also increasingly sceptical about any rate rising happening in 2018, unless the ECB moves ahead of schedule and raises rates at the end of 2018; instead of mid-2019 as in our forecast.

However, today's announcement shows that the Riksbank can still surprise markets with its dovishness, and the scale of the gap between the bank and the market. The already significantly undervalued krona fell to its lowest level against the euro since the height of the financial crisis in 2009, as investors shed the currency. Given the continued pressure on the currency, as well as domestic concerns about the tightening labor market, and the risk of a housing bubble; we continue to argue that significant risks remain that the central bank will be forced to raise rates sooner rather than later to address these structural imbalances. As a result of the risks associated with a housing bubble and undervalued currency, we maintain that ignoring these issues to focus only on the 2% target is a risky approach, particularly for the normally cautious Riksbank.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsweden-maintains-policy-rate-at-april-meeting.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsweden-maintains-policy-rate-at-april-meeting.html&text=Sweden+maintains+policy+rate+at+April+meeting+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsweden-maintains-policy-rate-at-april-meeting.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Sweden maintains policy rate at April meeting | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsweden-maintains-policy-rate-at-april-meeting.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Sweden+maintains+policy+rate+at+April+meeting+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsweden-maintains-policy-rate-at-april-meeting.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}