Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jun 13, 2018

Risk of hooliganism at the 2018 FIFA World Cup

The 2018 FIFA World Cup begins tomorrow in Russia - the first ever to be held in Eastern Europe and the first in Europe since 2006. Football/ Soccer is a sport of great passion - both on and off the field. Whilst the passion on the field is often displayed with some pretty heart-stopping plays, the passion off the field is often exhibited in what we commonly call Soccer Hooliganism.

Soccer hooliganism is nothing new. A quick search shows that public disorder and violence around soccer's forerunners goes back goes back centuries . But as an organized phenomenon it most obviously became common amongst British football fans from the 1960s onwards. Since then, it has been seen almost everywhere that professional soccer is played. While we normally look at political and terrorist violence - and have done so in relation to these very games - our team took a moment to look at the risk assessment for these games in terms of soccer hooliganism and what it can mean for spectators, local authorities, and the towns where the games are being held.

Key findings

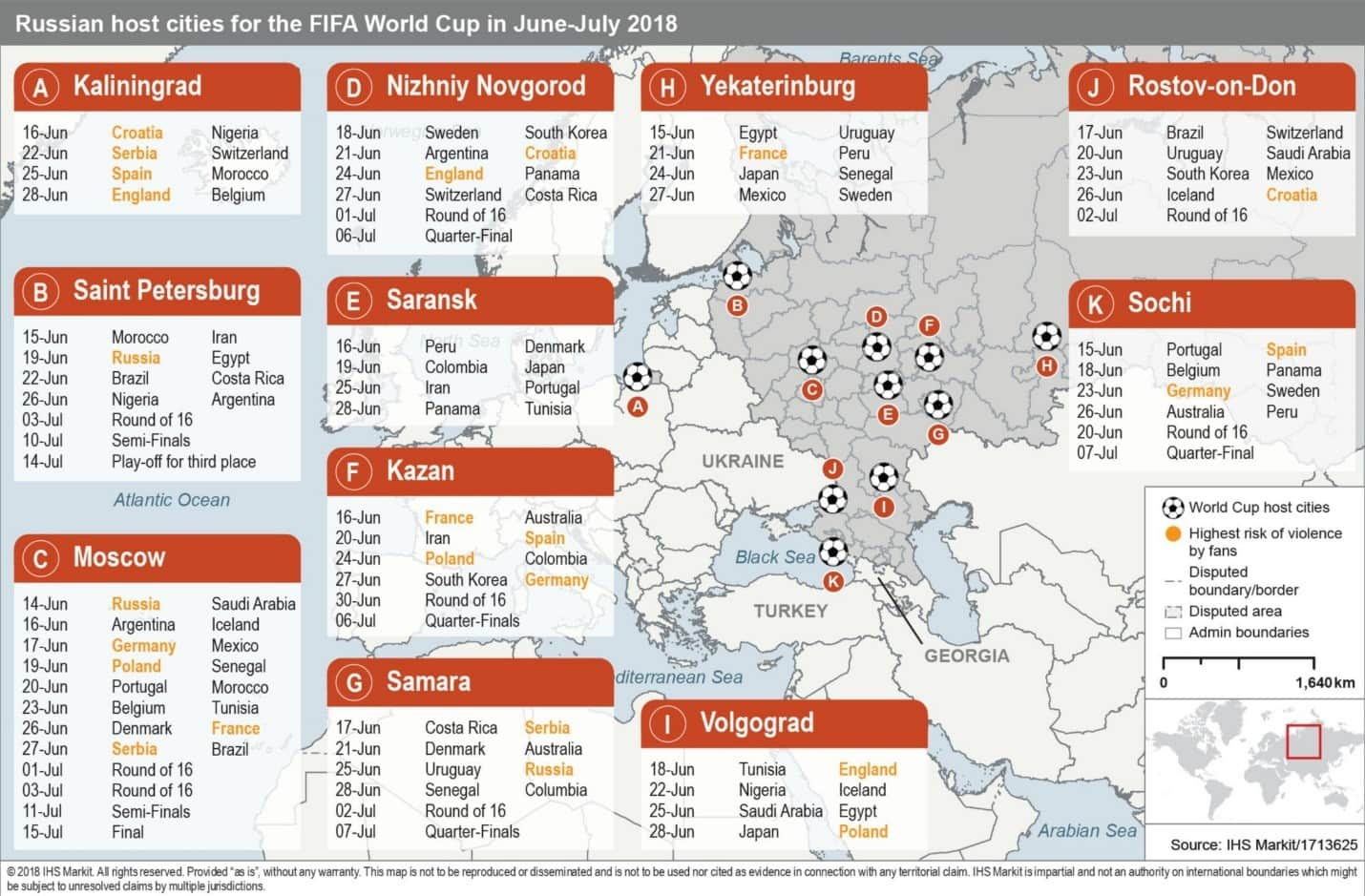

- Brawls by football fans are most likely if the teams of England and Russia (10 or 11 July), France and Russia (6 or 7 July), Germany and Poland (6 or 7 July), and Croatia and Serbia (10 or 11 July) are paired against each other in the knockout stages of the tournament.

- A heavy police presence is likely to be a partial deterrent for brawls, as well as mitigating their impact if they do occur. Despite this, the probable availability of alcohol at fan zones and stadia (local authorities have some flexibility in deciding) is likely to act as one driver of brawls, especially around high-stakes matches.

- Police will respond very forcefully to any fan violence, including with tear gas and rubber bullets, and they will most probably conduct indiscriminate mass detentions.

- Co-operation between foreign and local police officers is likely to be jeopardized by the current political animosity between Russia and many Western European countries. This poses a risk of foreign officers not being able to preemptively spot potential troublemakers, and of detainees being held for longer than usual, especially from England, Germany, Poland or Croatia, provided that these fans are the most likely to engage in fighting.

Drivers of potential fan violence include past

animosities and political influences

Political, historical or racial stereotypes or grievances

are likely to trigger brawls. Such grievances include the

occupation of Poland by Germany in the Second World War, as

indicated by nationalistic slogans chanted by German fans at Euro

2008 in Klagenfurt. Another driver is the current political

animosity between Russia and many Western European countries, and

the narrative of unfair victimization felt by many Russians (and

promoted by Russian authorities).

Games to keep an eye on

England and Russia could only play each other in the semi-final in St Petersburg on 10 July, or in Moscow on 11 July. Before that, the likelihood of confrontations between the respective fans is mitigated by the fact that the two teams are not in the same city simultaneously during the group stage.

Fans of both Germany and Poland are likely to be in Moscow over 17-19 June, but the highest risk of brawls between them would be if Germany and Poland play each other, which could be in the quarter-final in either Kazan on 6 July or in Samara on 7 July.

Serbia and Croatia could play each other in the semi-finals in St Petersburg on 10 July or in Moscow on 11 July. Both Croatia's and Serbia's fans will be in Kaliningrad in the group stage, but the time between the matches mitigates the risk of confrontation between them; Croatia's match with Nigeria is on 16 June, while Serbia's with Switzerland is on 22 June. France and Russia could play in the quarter-final in Nizhniy Novgorod on 6 July or on 7 July in Sochi.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2frisk-hooliganism-2018-fifa-world-cup.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2frisk-hooliganism-2018-fifa-world-cup.html&text=Risk+of+hooliganism+at+the+2018+FIFA+World+Cup+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2frisk-hooliganism-2018-fifa-world-cup.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Risk of hooliganism at the 2018 FIFA World Cup | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2frisk-hooliganism-2018-fifa-world-cup.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Risk+of+hooliganism+at+the+2018+FIFA+World+Cup+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2frisk-hooliganism-2018-fifa-world-cup.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}