Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jun 13, 2018

Possibility of prolonged fractured governance in Spain raises growth risks

Despite likely pressure from key supporters in parliament for Pedro Sánchez's new government to shift economic policy direction towards a more formally distributive model, Sánchez is unlikely to alter Spain's current macroeconomic direction during 2018.

First, his new centre-left minority PSOE government has inherited an economy that is performing well on the broad growth measure, and would be unlikely to risk damaging the upturn when it is facing elections within the next year, and possibly before end 2018, for an attempt to appeal to the left which is not guaranteed success. Second, given Sánchez has assumed office as prime minister at the head of a PSOE government due to a vote of no-confidence, and not by being elected as the majority party, it is doubtful how much of a mandate he can legitimately claim to overturn former prime minister Mariano Rajoy's policies. Any wholesale attempt to substantively change Spain's overarching economic policy before an election is therefore likely to be highly contentious, and legislation to that effect would be unlikely to gain parliamentary approval. As such, the government has committed to adhere to the 2018 national budget, and its fiscal target with the general government budget deficit expected to narrow from 3.1% of GDP in 2017 to 2.2% of 2018.

Our baseline therefore remains that Sánchez is likely to maintain broadly neutral economic policy positions through 2018 with the objective of getting a stronger mandate for elections and to avoid being forced into elections earlier in 2018 by an inability to manage parliamentary business effectively.

We anticipate a moderate impact on Spain's growth performance in the remainder of 2018 from the recent bout of political upheaval. The economy has shown commendable resilience to the events in Catalonia, Spain's largest economic hub. Indeed, strong short-term PMI and employment indicators continue to signal strong activity in the second quarter of 2018, with real GDP probably expanding by at least 0.6% quarter-on-quarter. However, we expect more tangible downward pressure on the 2019 growth outlook, and for several reasons.

- If the general election occurs in 2019, it is likely to produce a messy outcome, doing little to push back the current political uncertainty.

- The prospect of higher crude oil prices in 2019, with our projection set to be raised from an average of USD67 per barrel to USD75.1. Spain is a major oil importer with higher than average weighting in its CPI index. Higher energy prices will hit already struggling households enduring relativity flat nominal earnings growth.

- Softer Eurozone economic data triggering less upbeat growth projections for the region, suggesting less robust Spanish export growth.

Next election likely to be shaped by pressures on

household economy

The next general election in Spain will need to address potentially

conflicting pulls, the pressure to make the current economic upturn

more inclusive, while remaining true to its fiscal

responsibilities. The lack of unifying themes does represent a risk

to Spain economic growth from 2019 onwards. Spain is still gripped

by a standard of living crisis, while its incidence or risk of

poverty is higher than its Eurozone peers, including Italy.

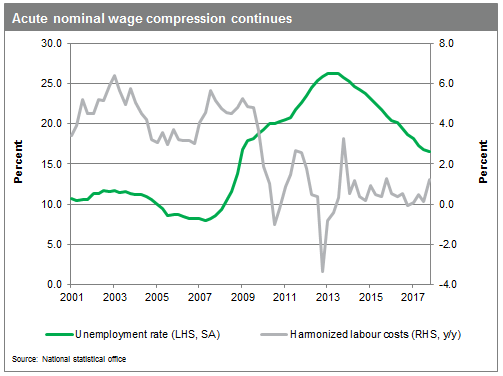

The situation may have eased with Spanish households enjoying some positive gains in real disposable income in 2015-17 in line with lower inflation, but the latter still remained around 6% below the pre-crisis peak by end-2017. Voters have endured a nominal wage growth compression since the beginning of the recovery, with labour costs per worker being just 1.3% higher at end-2017 when compared to early 2014, the start of the recovery. In addition, downward pressure on real wages could intensify during the second half of 2018 and 2019, with marginal nominal wage growth expected to fall further behind higher consumer price inflation as a result of more elevated energy prices.

Meanwhile, many households are trapped into a cycle of temporary employment contracts, with several labour market reforms falling to push back the duality in Spanish labour market. Specifically, the number of workers of temporary contracts in Spain remains an outlier, standing at 26.1% of dependent employment in 2017, compared to 11.2% in the OECD and 15.4% in Italy. This suggests that firing workers on permanent contracts in Spain remains too costly and laborious. And, many voters on temporary contracts complain of poor job security, limited spending power and no access to the retail mortgage market.

Overall, the next general election could focus on the distressed state of parts of the household economy, highlighted by compressed real income growth, high youth unemployment and poor job security for some.

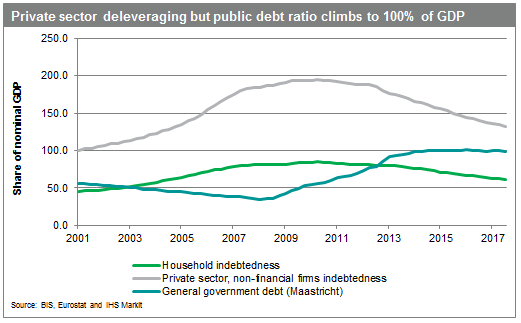

Like in Italy, Spain has limited fiscal muscle to address these ills, with its challenging fiscal metrics requiring continued vigilance. Specifically, Spain's public debt ratio has climbed notably from a historical low of 35.7% of GDP in 2007 to a peak of 100.4% in 2014 before edging down to 98.3% in 2017. This implies notably heavier debt redemption schedules alongside diminished resilience to any notable financial market stress. The fiscal landscape is further complicated by its primary budget position remaining in deficit (at 0.5% of GDP in 2017), underlying the need for continued caution.

The end of decisive governance after the inconclusive general elections in late 2015 and June 2016 has stopped the conveyor belt of policies and reforms that helped Spain to pull away from its lengthy recession that ended in early 2014. With the economic upturn now firmly established, the political consensus borne out of the crisis has evaporated, and has been replaced by more fractured governance. This suggests there is limited appetite for further reforms and the need to evolve a structural fiscal plan to address its public debt mountain.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpossibility-of-prolonged-fractured-governance-in-spain-raises-growth-risks.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpossibility-of-prolonged-fractured-governance-in-spain-raises-growth-risks.html&text=Possibility+of+prolonged+fractured+governance+in+Spain+raises+growth+risks+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpossibility-of-prolonged-fractured-governance-in-spain-raises-growth-risks.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Possibility of prolonged fractured governance in Spain raises growth risks | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpossibility-of-prolonged-fractured-governance-in-spain-raises-growth-risks.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Possibility+of+prolonged+fractured+governance+in+Spain+raises+growth+risks+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpossibility-of-prolonged-fractured-governance-in-spain-raises-growth-risks.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}