Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Nov 23, 2020

India and China decoupling

One of the key features of the US-mainland China 'decoupling' over the coming years will be how it forces other countries to strategically realign their external relations, sometimes counter to their narrowly defined economic interests. The resetting of the relationship between the world's two largest economies is certainly quickening such a realignment in what will be its third largest by 2050. India's foreign policy has been studiously non-alignment since independence in 1947. With regard to China, successive Indian governments settled on an awkward separation of commercial relations and broader strategic concerns. A stand-off near the Doklam Plateau tested that separation in mid-2017. The military incidences in Ladakh along the 'Line of Actual Control' (LAC) this summer collapsed it. The Indian government is now more openly working with the US to check Chinese strategic advances than ever before, with implications for businesses operating in any of these three countries and beyond.

Not business as usual

Within weeks of the Ladakh confrontation, India announced all direct and indirect investment from countries that have land borders with India would require government approval (without explicitly mentioning China). The state government of Maharashtra suspended three Chinese automotive projects, citing the violent standoff in the Himalayas. By late June, India's Ministry of Information and Technology had banned 59 mostly Chinese mobile applications on national security and privacy grounds. The process of course pulled in private businesses that participate in both markets. Google and Apple were required by to remove the proscribed apps from their play stores and telecommunication and internet service providers were instructed to block related internet protocol (IP) addresses and domain names. On 1 July, the Indian government announced Chinese companies would be prohibited from bidding for highway construction contracts, even via joint ventures, amid calls by major Indian media outlets for consumer-led boycotts of Chinese goods.

Meanwhile India, Australia, and Japan began negotiating a Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI), implicitly but clearly to reduce their reliance on China. The SCRI will prioritise healthcare, automotives, aviation parts, communications technology, electronics, and other high-value intermediate goods. In July, the Indian government appointed Gourangalal Das, a senior diplomat close to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to head India's representative office in Taiwan. This signaled Taiwan's increasing importance to India, even if India officially adheres to the 'One China Policy'. Taiwanese manufacturers, especially in the highly prized telecoms sectors have already begun to diversify production from China to India. Apple's Taiwanese supplier, Foxconn, began assembly of the flagship iPhone 11 in India earlier this year and promised a further USD1bn of investment. Indian policymakers' minds will have been concentrated by Ladakh. But also they have likely been emboldened by recent US engagement with Taiwan, including the 10 August state visit by the US Secretary of Health and Human Resources - the most senior US official to visit Taiwan since 1979. (Like India, the US officially accepts the One China Policy.)

Economic impact, direct and indirect

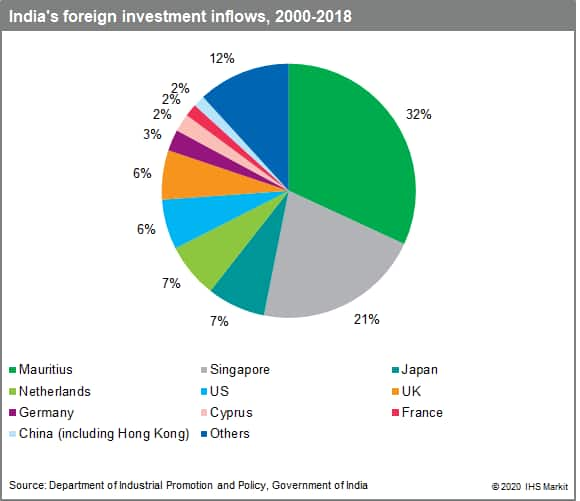

The bilateral economic relationship between Asia's largest and third largest economies, however, is small. India accounted for only 2.1% of China's total foreign investment outflows in 2018 and China accounted for less than 1% of India's inward flows in 2019 (latest data), broadly consistent with annual levels since 2000. India-China bilateral trade stands at around USD93 billion, with India running a deficit of about USD57bn.

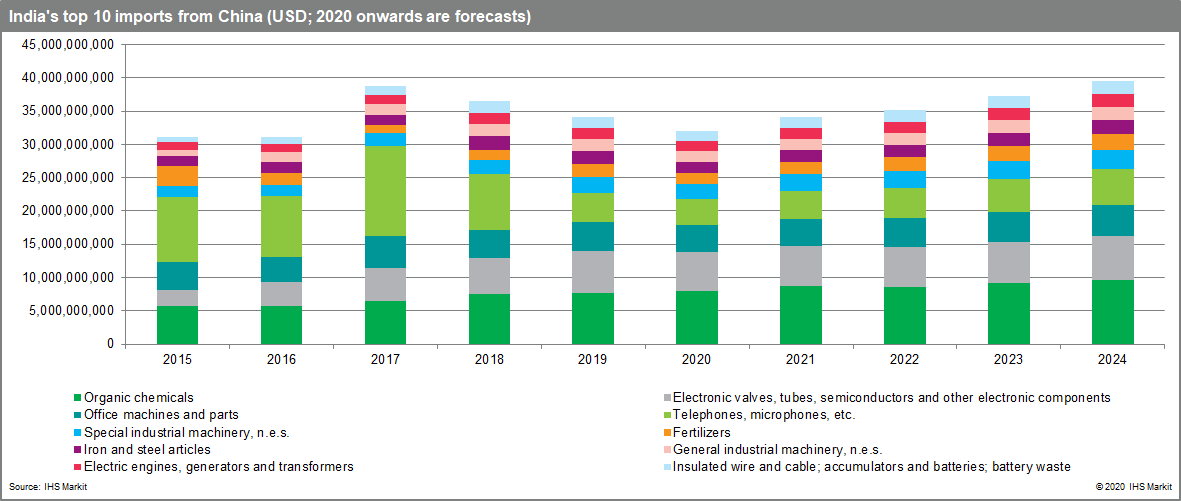

But India is exposed in some strategically important sectors. These includes telephones, semiconductors - both of which India wants to manufacture indigenously and export. Earlier this year, India announced a 10% duty on the import of smartphones, probably to deter Chinese phones from flooding domestic markets. Imports from China contribute heavily as value-added goods in India's exports more broadly. Research published in October in Mint, a widely respected Indian business publication, showed China's share of foreign value-add implied in Indian exports grew from 6% in 2000 to 26% in 2018. Furthermore, Chinese capital often seeds India's thriving start-up, which India's capital-depleted and heavily loan-impaired banking sector cannot match. (IHS Markit's Banking Risk Service currently scores systemic banking risk in India at 50/ 'significant risk'.) At least 69 Chinese companies have invested in more than 100 Indian startups, and more than 60% of all Indian startups valued at over USD1bn have at least one Chinese investor, primarily in the e-commerce, retail, logistics and mobile payments sectors. Data from India's Ministry of Commerce, show Chinese investment in Indian startups increased to nearly USD4 billion in 2019, double that in 2018.

Limited decoupling

Despite this, Indian regulators - like others in the US, the EU, UK, Japan, and Australia - will almost certainly intensify scrutiny of new investment from China. In September Indian officials stated they had begun even retrospective scrutiny of Chinese investments, focusing on platforms that collect personal data. A new parliamentary committee to review the risk to national security interests is now likely within the coming year. Also, India's Department of Telecommunications has reportedly made an unofficial request for public-sector telecom companies to not purchase equipment from Chinese telecom companies Huawei and ZTE - similar unofficial lobbying of the private sector is highly likely. India's respective parliamentary committee held a private meeting in October to recommend restricting Chinese participation in forthcoming 5G trials. India will be keen to cooperate instead with Japan (NTT) and the European Union (Ericsson, Nokia), while promoting India's Reliance Jio. Importantly, Jio is already a member of the US-backed Clean Network Initiative.

The India-China decoupling will then be different and similar to that larger US-China one by which it is compounded. The direct bilateral relationship is much smaller so there will be a much smaller impact on the global economy. But similar to the US-China decoupling, there will be a sharp focus on strategically important sectors, especially communications technology, and careful scrutiny - in national security terms - of the data captured by new ventures and who has access to that data. Longer term, as India's economy becomes the third largest in the world, and if initiatives with Taiwan, Japan, and Australia are successful, the economic and supply chain implications of the deteriorating India-China relationship are likely to be much more significant.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-and-china-decoupling.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-and-china-decoupling.html&text=India+and+China+decoupling+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-and-china-decoupling.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=India and China decoupling | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-and-china-decoupling.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=India+and+China+decoupling+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-and-china-decoupling.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}