SUMMARY

Should investment results be attributed to skill or luck? Genuine skill is likely to persist, while luck is random and fleeting. Thus, one measure of skill is the consistency of a fund’s performance relative to its peers or to its benchmark. The Persistence Scorecard shows that regardless of asset class or style focus, active management outperformance is typically short-lived, with few funds consistently outranking their peers or benchmarks.

Recent years have blessed (or cursed) financial markets with plenty of volatility and narrative regimes. From a slow interest-rate-hiking cycle through the chaotic drawdown of the initial COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns,to a market powered by large technology companies and later extending to other sectors as the world re-emerged, this environment provided an excellent test of true fund management skills and adaptivity.

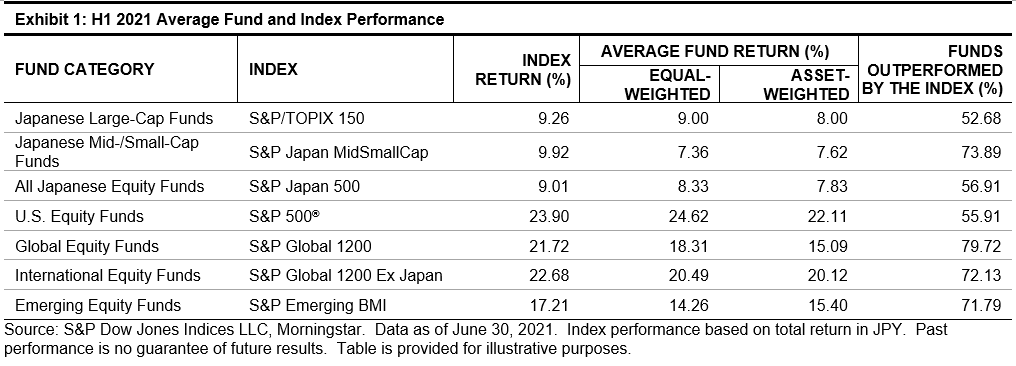

Sadly, what worked in one period was unlikely to persist in the next. Exhibit 1 shows that the top quartile funds in the 12-month period ending in June 2019 continued to succeed over the next year—perhaps because many of the winners of the late pre-pandemic expansion were often the same companies that benefited the most immediately following the lockdown. However, as the economy continued to recover, the rest of the market caught up, and those superstar funds quickly reverted to the mean. Within two years, a mere 4.8% of these June 2019 domestic equity winners remained in the top quartile (see Report 1a).

Sign up to receive updates via email

Sign Up

Even expanding the definition of success to simply beating the median fund’s return, fewer than 27% of any equity category’s top-half funds in June 2019 managed to stay in the top half through June 2021 (see Report 1a).

Widen the time horizon to five years, and the picture looks even more bleak. Even in the best category for persistence, just 3.2% of multi-cap funds managed to stay in the top quartile for each year. Mid-cap funds were especially disappointing, with no funds accomplishing that feat (see Report 2).

Some statistically minded readers might note that these numbers are occasionally better than what would be expected if fund performance was randomly distributed. For example, the odds that a top-quartile fund in one year could remain in the top quartile for the next four consecutive years might be calculated as (25%)4 = 0.39%, and the 3.2% referenced above is substantially better than that. While the persistence report does not prove that fund performance is completely random, from a practical or decision-making perspective, it reinforces the notion that choosing between active funds on the basis of previous outperformance is a misguided strategy. After all, there remains a 96.8% chance that a top-quartile fund will not stay in the top quartile for the next four years.

Another way of evaluating performance persistence is by comparing fund performance against their benchmarks. We first identify funds that beat their benchmarks in the one-year period ending in June 2019, net-of-fees. We then examine whether these funds continue to outperform during each of the next two one-year periods. Our result shows that past outperformance did not typically help identify superior performing managers in the future.

For example, out of 819 large-cap funds, 244 (or 29.8%) managed to beat the S&P 500® in the 12- month period ending in June 2019. However, only 128 of those 244 (52.5%) were able to keep their positive alpha in the next 12 months. By the end of June 2021, only 30 (12.3%) succeeded in repeating their outperformance relative to the benchmark (see Report 1b).

Previous SPIVA U.S. Scorecards showed that 36.8% and 41.8% of all large-cap funds outperformed in the 12-month periods ending in June 2020 and June 2021, respectively. An investor choosing funds randomly might thus expect a 36.8% * 41.8% = 15.4% chance of picking a fund that would outperform for two consecutive years, higher than the 12.3% realized—reinforcing the notion that fund alpha is likely fleeting.

Unsurprisingly, the one pattern that did hold across equity funds was the tendency of the poorest-performing funds to close. Fourth-quartile funds were almost always the most likely to merge or liquidate over the subsequent three- and five-year windows, with 52% of the bottom-quartile mid-cap funds from the June 2011–June 2016 period disappearing by June 2021. In fact, closing their doors was the most likely outcome in four out of five equity categories for fourth-quartile funds in that period (see Report 5).

Style changes did not appear to be particularly correlated with fund performance. Top, middle, and bottom performers within a category all generally had similar chances of style drift over three- or five-year periods. Multi-cap funds had the highest percentage of style change, with 28% making a change over three years and 41% over five years (see Reports 3 and 5).

Fixed income funds showed similar results to equities, with pockets of one-year persistence decaying over longer periods. In 8 of the 13 categories considered, no top-quartile funds from June 2017 maintained that status annually through June 2021 (see Report 8).

Transition matrices showed slightly more evidence of fixed income fund persistence. Over the five-year horizon, in 6 of the 13 categories, 50% or more of top-quartile funds remained in the top quartile. However, there were only two categories with greater than 20 funds that qualified within each quartile, perhaps leading to small sample size effects (see Report 11).