Record-beating warm weather worldwide so far in 2015 could make it the hottest year on record. This is fitting climatic context ahead of the 2015 U.N. Climate Change Conference taking place in Paris over next two weeks. Earth is warmer now than it has been for over 90% of its 4.6 billion year history, and there's no sign of any slowdown (McGuire, 2014). The British Met Office estimates that global temperatures between January and September of this year were just over 1 degree Celsius above the 1850-1900 average--halfway to the 2 degrees Celsius increase from that time that many governments have committed to as a benchmark limit to avoid catastrophic levels of warming. (Watch the related CreditMatters TV segment titled "The Rating Impact Of Natural Catastrophes Due To Climate Change," dated Nov. 26, 2015.)

View the infographic at www.spratings.com/climatechange.

That raises a very relevant question from Standard & Poor's Ratings Services' view: As the planet as a whole gets hotter, what are the potential consequences of climate change on particular nations' sovereign creditworthiness? It's a fairly complicated exercise, and to make our first-ever informed estimates requires us to assess climate change's impact on economic and individual sovereign ratings factors.

Extreme weather conditions that likely lead to a radical rise in meteorological disasters, and their magnitude, are increasingly becoming part of everyday lives. According to the World Meteorological Organization, more than 370,000 people died in extreme weather incidents between 2001 and 2010--a 20% rise over the previous decade. Our planet is expected to become even more lethal, e.g. given the future trends in coastal urbanization, with rising sea temperatures and levels resulting in more frequent and more devastating storms, particularly in the tropical regions. In fact, extreme precipitation events have increased significantly at high and middle latitudes in the second half of the 20th century, and tropical cyclones worldwide are becoming stronger, with a 250% increase with sustained wind speeds exceeding 175 km per hour (McGuire, 2015). For small island nations, such as Maldives in the Indian Ocean and the Marshall islands in the Pacific, a one-meter rise in sea level would flood up to 75% of their dry land, making the islands uninhabitable. Other major concentrations of population at risk from such events are those living by river deltas, including in Bangladesh and Thailand.

Public awareness of these risks is growing. Indeed, the Global Risks 2015 report by the World Economic Forum (World Economic Forum, 2015) shows that survey respondents mostly consider environmental risks will grow faster over the next decade than any other risk category. Another recent global survey, with respondents from 40 countries, confirms this. Its respondents cited climate change as their biggest global concern, even ahead of global economic instability and specific regions' security concerns (Pew Research Center, 2015).

The consequences of climate change will become even more tangible in coming decades, with more frequent and more destructive storms and floods as well as shifts in weather patterns due to rising average global temperatures.

Climate Change And Our Sovereign Ratings Methodology

Standard & Poor's sovereign credit rating methodology doesn't specifically refer to risk of climate change impact. However, it makes reference to natural peril as an "event risk" and a situation where a sovereign would be subject to "constant exposure to natural disasters or adverse weather conditions." While not explicit, the latter is very much in line with the description of potential consequences of climate change (see "Sovereign Rating Methodology," published Dec. 23, 2014, on RatingsDirect). In general, however, the most likely effect of climate change via natural catastrophes on sovereign ratings would be indirect rather than direct, through a weakening of the fundamental factors that determine a sovereign's rating, such as our economic, external, fiscal, monetary, and institutional assessments. Similar to the ratings implications of aging societies (see "Global Aging 2013: Rising To The Challenge," published March 20, 2013), our criteria implicitly capture the effect of climate change and natural disasters on the sovereigns we rate.

Quantifying The Impact Of Climate Change

This is our initial attempt to quantify the severity of the economic and ratings impact of climate change, and we're focusing on two perils: tropical cyclones (and their associated storm surges) and floods. Of course, climate change can exacerbate other, non-meteorological natural hazards. Due to limited data availability, we had to omit drought and some other hazards related to climate change, but we recognize that they, too, can affect lives and economic activity, especially in low-income developing sovereigns with important agricultural sectors. Our results presented here should therefore be understood as merely a partial analysis of how climate change would affect sovereign ratings.

To quantify climate change impact for each country, we start by simulating direct damage to property and infrastructure resulting from a disaster whose severity would be expected to occur once every 250 years. It's important to note that our analysis isn't aimed at quantifying the impact of climate change in totality. We're just looking at the implications climate change will have on a once-in-every-250-year catastrophe event. We're not including all other gradual and accumulating impacts. As a starting point, we use estimates of property damage-to-value that could result from natural disasters under climatic conditions prevailing today (for a more detailed discussion of our assumptions, see "Storm Alert: Natural Disasters Can Damage Sovereign Creditworthiness: Methodological Supplement," published on Sept. 24, 2015). We then reassessed this impact by modifying the model's hazard component to reflect climate change, which will lead to higher potential damages (see Appendix). The result: Once-in-250-years disasters become more damaging as climate change increases.

The mainstream in climate science takes the view that global warming will make meteorological natural catastrophes more frequent and more severe than at present. That assumption also underlies our analysis here. It also means given the forecasts for increased frequency of extreme events, what is now considered a once-in-250-years event could become, say, a once-in-50-years event. Depending on emissions scenarios, warming might not be stopped by 2050 and could go on beyond 2100. In the very long term, therefore, our estimates may well underestimate climate change risks to sovereign creditworthiness (see Appendix). It's important to reiterate that our simulation's aim isn't to incorporate all climate change effects for an individual sovereign. Instead, the key is to analyze how the impact of climate change through 2050 affects the severity of a 250-year event (tropical cyclone or flood) and its implication on the sovereign's economy and creditworthiness.

The direct damage data we use were compiled and provided by reinsurance company Swiss Re. The data estimation is based on the open-source climada model (Bresch, 2015) and further proprietary information provided by Swiss Re (see Appendix). The data set contains 30 estimates of 250-year tropical cyclone events and 14 estimates for 250-year flood events.

Compared to our recent report on natural catastrophes, here we're extending our analysis to Africa (previously not covered) and notably the Caribbean region (increasing the number of sovereigns analyzed). It's worth recalling that the direct damage data include only the estimated value of the physical destruction of private and public property, including infrastructure. It doesn't include the knock-on effects on economic growth because of the concomitant impact on productive capacity or disrupted supply chains. We model these secondary impacts separately. A comprehensive assessment should include a projection of economic development in the future. This can encompass more densely populated cities, newly constructed infrastructure and enlarged industrial and settlement areas, which may increase the future potential damage following a natural disaster.

The economic and sovereign rating impact is expressed in relative GDP terms. Under the reasonable assumptions that absolute property damage (in constant-dollar terms) grows proportionally with absolute property values (equally measured) and that property values move proportionately with real GDP, we quantify the impact of climate change by solely increasing the damage-to-value ratio of a natural catastrophe.

The sample analyzed is limited by data availability. Many of the 130 sovereigns we currently rate aren't in the sample because data were unavailable or we considered damage estimates to be too low to have any ratings impact. Our simulations take into account existing insurance coverage for the sovereigns concerned, as made available by Swiss Re. The impact of climate change could, therefore, still be ratings-relevant for sovereigns left out of this report. We recognize that alternative reasonable specifications and modeling could lead to equally valid but differing damage estimates. Nevertheless, and in full recognition of those caveats, we consider the Swiss Re dataset to be the most comprehensive and cross-country comparable available to us.

We simulated the macroeconomic impact and sovereign rating outcomes as described in our September 2015 "Storm Alert" report and methodological supplement. For the purpose of this analysis we assume that, all things being equal, the ratings distribution will remain broadly unchanged in 2050. In fact, sovereign default probabilities have on average empirically not changed significantly over a time period of 35 years, like we're covering here. Indeed, our historical ratings transition data suggest that the relative rank ordering is likely to remain broadly unchanged in the future (see "2014 Annual Sovereign Default Study And Rating Transitions," published on May 18, 2015). Finally, it's also worth recalling that the hypothetical rating changes this simplified model generates are not to be misunderstood as Standard & Poor's definitive view on likely future ratings trajectories.

What The Simulations Show

In the following sections, we analyze the results of our simulations of the impact of climate change on sovereigns. As in our September 2015 "Storm Alert" report, the benchmark is an event that occurs once every 250 years on average. But here we're including the corresponding damage assumptions from climate change. Differences between individual perils are recognized in the direct damage estimates, which is the main factor behind the macroeconomic and ratings impact. The simulations of economic, external, and budgetary variables are uniformly applied across the sample and do not discriminate among the two perils, tropical cyclones and floods.

Overall, in 44 natural catastrophes in 38 countries, climate change increases the expected once-in-250-years damage-to-value ratio significantly, on average by about 25%. The negative rating impact of the catastrophes due to climate change increases accordingly on average by about 20% compared to a scenario not including climate change.

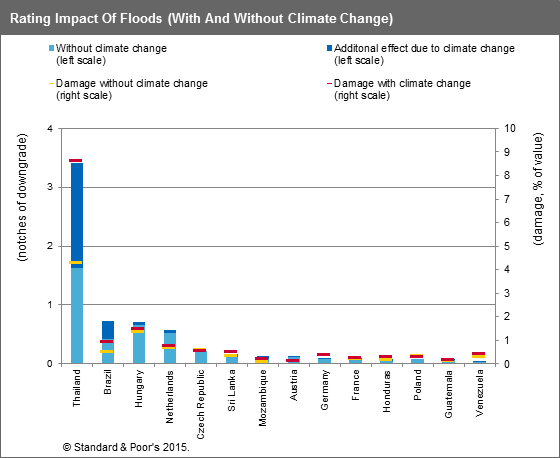

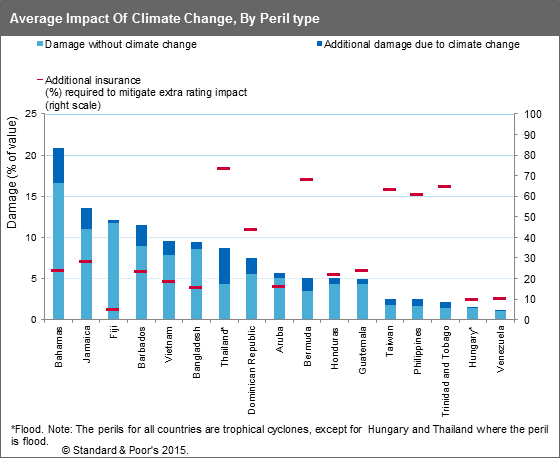

However, important differences exist among the sovereigns covered in this report. The impact of climate change is far more important for emerging and developing sovereigns than the advanced economies. In terms of average impact, our simulations show that tropical cyclones are more damaging than floods. Most notable climate change risk increases include tropical cyclones in the Bahamas, Barbados, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Vietnam, and floods in Thailand. Regarding Thailand, the impact is particularly severe: It doubles the potential flood damage compared to a status-quo scenario without climate change.

Nevertheless, we expect advanced sovereigns to also see significantly raised potential direct damage from climate change. For example, that from tropical cyclones in the U.S., New Zealand, or Japan would be higher by 45%, 50%, and 64%, respectively, albeit from a relatively lower base than for Caribbean economies. The impact of floods in Europe appears quite small according to our simulations.

In our view, some countries will be able to adapt to the challenges associated with climate change. But the speed of change could be so rapid as to make this all but impossible for the most vulnerable nations in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere in the developing world.

Climate Change Could Lead To More Destructive Floods And Tropical Cyclones

The Swiss Re direct damage data assessing the impact of climate change on tropical cyclones and floods indicate a particularly large increase in potential direct economic damage (of more than a 1 percentage point increase in value compared to the no-climate-change scenario) for the Caribbean sovereigns like Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Vietnam (all tropical cyclones; see chart 1) and Thailand (floods; see chart 2 and tables 2-9 for detailed data on damage caused as well as key results of our economic simulations). In some other sovereigns that are geographically exposed to tropical cyclones, for example Bangladesh and Fiji, the increase in direct damage is not so significant. But this needs to be viewed in the context that a natural catastrophe would already be extremely devastating under current climatic conditions (8.6% and 11.7% of value in Bangladesh and Fiji, respectively). Climate change would only be aggravating an already very vulnerable position.

Conversely, the impact of climate change is likely to reduce potential direct damage from floods in Poland and the Czech Republic, although ever so marginally. This is due to the likely decline in floods usually caused by the combination of heavy rains and snow melting. With warmer temperatures, snowfall will be lower and so will be meltwater.

Chart 1

Economic impact: For each of the sovereigns analyzed, our damage estimates represent an immediate severe negative economic shock, and our simulations of macroeconomic impact show worsening GDP per capita losses (in cumulative U.S. dollars) due to climate change. In the most affected sovereigns, the per-capita income losses range from about 1.6% (Bermuda) to 8.5% (Thailand), compared to a simulation with no climate change.

Fiscal impact: As a result of the economic shock, we would expect government finances to deteriorate due to the necessary public spending on reconstruction following the disaster, as well as the negative cyclical effect of the resulting economic downturn. Climate change alone would increase government debt in the affected sovereigns by between slightly more than 4% of GDP in Vietnam and 42% of GDP in the Bahamas, compared to a no-climate-change scenario (see table 9).

Chart 2

External impact: Adding the adverse impact of climate change to the devastation of a tropical cyclone or flood would likely further depress exports and increase imports, such as food, medical supplies, and reconstruction-related materials. As a result, the external position of the affected sovereigns would worsen compared with a no-climate change scenario. We expect the projected weakening of current account balances, in particularly the decline in current account receipts, to contribute to a significant deterioration in the external debt position of several sovereigns, especially in Bahamas, Bermuda, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Thailand.

Chart 3

Ratings impact: The projected economic consequences translate into an adverse impact on sovereign creditworthiness as a consequence of more damaging one-in-250-year catastrophes. We estimate that on average and across the sovereigns in our sample, the simulated sovereign ratings would decline by about a fifth of a notch, compared with our baseline rating in the absence of climate change. However, the sovereigns concerned show wide differences. For example, for the most affected sovereigns listed above, the hypothetical ratings would decline by at least half a notch and almost two notches for Thailand. Regarding that country, while the hypothetical rating impact is very large, the risk of the event happening is remote (once in only 250 years), and the likelihood that it will happen in our ratings horizon (5-10 years) is small. Therefore, the analysis here doesn't indicate structural weakness that the rating should reflect, but rather a possible ratings cliff in a rare but not impossible event.

The deterioration in the Caribbean sovereigns would mainly result from the deterioration in our assessment of economic risks (Bahamas) or fiscal risk (Bermuda, Jamaica) accompanied by external risk (Dominican Republic). In the case of Thailand floods, the deterioration would likely be broad based, led by fiscal and external risk deterioration, followed by increases in economic and debt risks (see tables 3 and 7).

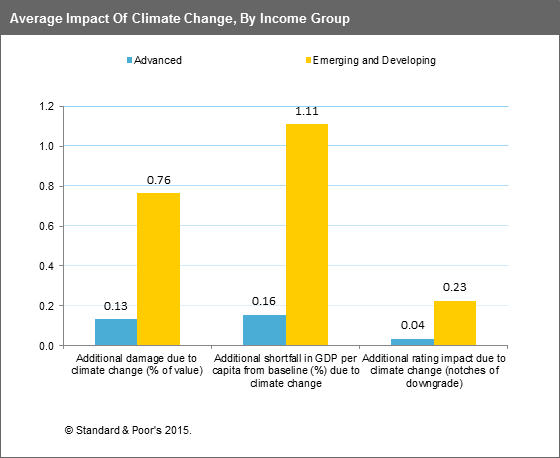

Wealthier Nations Should Better Withstand Climate Change Impacts

The results of our climate change simulations are in line with our findings from the September 2015 "Storm Alert" report on the impact of natural disasters in the absence of climate change. There we observed that richer sovereigns' ratings feel less impact from a natural disaster. We believe this is due to existing economic and financial resilience, but also a more developed insurance market. Moreover, an equally adverse climate change impact will comparatively have more significance for the ratings of emerging and developing sovereigns than for the wealthier ones.

Chart 4

In terms of the impact on economic growth trajectories, again emerging and developing sovereigns would be the most affected, with an estimated average decline in income per capita of about 1.1 percentage points, compared with the no-climate-change scenario (see chart 4). The advanced sovereigns display much more resilience, with less than a 0.2 percentage point decline. As a result, the rating impact is on average the highest for emerging and developing sovereigns, with practically no impact for advanced sovereigns' ratings, reflecting the smaller expected damage and their relatively higher resilience.

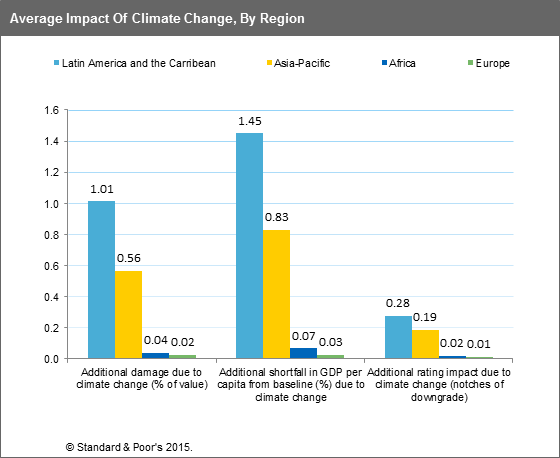

The Caribbean And Asia-Pacific Are Most At Risk

In terms of geographic impact, the average potential direct damage for all the perils considered in this study is the highest for sovereigns in Latin America and the Caribbean (more than 1 percentage point of value increase compared to no-climate-change scenario), followed by Asia-Pacific (more than 0.5 percentage points higher). This reflects their increased exposure to tropical cyclones and floods compared to the rest of the world (see chart 5). The average potential additional direct damage from climate change for sovereigns in Europe and Africa is much lower in relative terms, at well below 0.1% of value. The additional average rating decline compared to the no-climate-change scenario for the Latin America and Caribbean sovereigns in this report would be almost 0.3 notches, followed by Asia-Pacific with about 0.2 notches.

Chart 5

Insurance Coverage Helps, But Preparedness Is Key

We have shown in our previous September 2015 "Storm Alert" report how larger insurance coverage of the assets damaged or destroyed by a natural catastrophe can, to some extent, mitigate the medium-term economic impact. Insurance coverage cushions the negative effect on the private sector, and insurance payouts help accelerate the restoration of damaged productive assets of the private sector. This boosts economic growth and raises the tax base. As a result, higher insurance coverage will also mitigate the ratings impact of natural catastrophes. This holds true if we account for changes in magnitude of disasters due to climate change, as we do in this report.

But here, we're shifting the angle at which we look at insurance. We use insurance coverage as a measure to quantify the cost of the ratings impact due to climate change. More precisely, we ask: What incremental insurance coverage would an economy need to fully offset the ratings impact due to climate change? To answer this question, we compute the additional insurance coverage ratio that would result in the same rating impact under a 250-year event under climate change would yield as under a 250-year event without climate change (taking as given actual insurance coverage ratios).

We caution that insurance can't offset all of the economic and ratings impact of a natural disaster. Even with insurance coverage at 100%, it will take time to rebuild infrastructure and other capital. During that time, government spending is likely to be at least as high as in the absence of a natural disaster while tax receipts will fall comparatively short, leading to a deterioration of the fiscal position. In our exercise, our measure of additional insurance coverage also aims to account for this loss in terms of the ratings impact.

The amount of additional insurance that would offset climate change impacts will, of course, not only depend on the additional direct damage likely to be caused, but also on the specific economic and fiscal circumstances of the economy in question. These factors determine the country's vulnerability to ratings downgrades. In Thailand, for example, when accounting for climate change, a 250-year event will wreak double the damage of the same event when assuming no climate change. But it will take an additional 74% insurance coverage, more than seven times the actual coverage ratio, to offset the impact due to climate change (see chart 6). This is because insurance cannot fully mitigate the higher fiscal costs of larger damage and the larger initial economic disruption. Therefore, to cut the rating impact from 3.4 notches (with climate change) to 1.6 notches (without climate change and with actual insurance coverage levels) with a much larger damage, insurance needs to overmitigate the negative economic and external assessments (while the fiscal impact is still larger with climate change than without it). In other words, an 8.6% damage-to-value ratio with 83% insurance coverage leads to the same 1.6-notch rating impact as a 4.3% damage-to-value ratio and 10% insurance coverage. But in the latter case, the role of fiscal factors in the downgrade is much higher than in the former.

Similarly, in case of a tropical cyclone in Jamaica, the damage under a climate change scenario increases to 13.5% from 11%, and the rating impact goes to 4.4 notches from 3.9 notches. Because the additional impact is smaller, it can be compensated with only 29% additional insurance coverage (up from 10% estimated currently). Like in the case of Thailand, the additional insurance would need to overmitigate the economic impact to offset the unavoidable negative fiscal implications. It's important to note, however, that while the required additional insurance is smaller, both the damage and the rating impact without climate change are already very significant, higher than in the Thailand example.

Chart 6

It is worth noting that smaller sovereigns and regionally close sovereigns with similar natural disaster exposure have been effectively sharing and hence diversifying risk through multilateral risk-pooling institutions. Both the Caribbean Cat Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF, www.ccrif.org) and the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative (PCRAFI, pcrafi.sopac.org) provide their member states with disaster risk-modeling and -assessment capabilities as well as risk-bearing capacity. In a similar fashion, the African Risk Capacity (ARC, africanriskcapacity.org) uses modern finance mechanisms such as risk-pooling and risk transfer to create pan-African climate-response systems that have been helping African countries meet the needs of people harmed by natural disasters.

Still, given that insurance alone is unable to fully offset the impact of climate change, for the most adversely affected sovereigns, studies have shown that they would benefit from strengthened local resilience. Depending on the region, up to 80% of the increase in damage results from economic development in hazard-prone areas, such as megacities in coastal regions. Studies in more than 20 countries around the world suggest that up to 60% of the damage can be cost-effectively averted (ECA, 2009; swissre.com/eca). Consider the Netherlands, with about a quarter of its surface below sea level, countless man-made canals, and large areas of reclaimed land. This makes the country highly exposed to both saltwater and freshwater floods, which materialized in a devastating storm surge in 1953, the country's worst natural disaster so far. Since then, however, successive Dutch governments have been building protection measures, allocating large amounts of their annual budget to keep up safety levels. As a result, a network of dike rings and river embankments is designed to withstand up to once-in-10,000-year events, which makes additional insurance coverage less necessary. This also explains the surprising absence of flood insurance in the Netherlands (see tables below for insurance coverage of individual sovereigns). Therefore, the extent to which insurance coverage can be effective depends to a large degree on the strength of the fundamentals supporting the rating, especially when the damage caused by the disaster is large.

High Stakes At The 2015 U.N. Climate Change Conference

Our simulations indicate that climate change-related natural hazards can harm sovereign ratings. In terms of average impact of climate change by peril, our simulations show that tropical cyclones and associated storm surges will be more damaging than floods as the earth's temperature rises. Geographically, ratings of sovereigns in the Caribbean and Southeast Asia appear to be most at risk. The additional climate change damage caused in richer countries is on average more moderate. Their higher level of preparedness, including insurance coverage, further reduces the economic and rating impacts for that prosperous group. Finally, our results confirm that a larger insurance coverage against natural hazards is on average associated with more likely mitigation of adverse economic implications of any climate change impact. The extent to which this can be effective, however, depends to a large degree on the strength of the fundamentals that support the rating, especially when the damage caused by the disaster is large.

The 2015 U.N. Climate Change Conference in Paris aims to achieve a legally binding and universal agreement to limit global warming. It's too early to say whether the conference will produce a clear-cut consensus on global policy or significant changes to emissions targets. Either way, if insufficiently addressed, we expect the significance of the climate change megatrend in assessing sovereign risk to only increase over coming decades. As evidence of the economic implications of climate change and extreme weather events becomes ever more concrete, sovereign ratings could gradually become more at risk as well.

Table 1

| Macroeconomic Snapshot (2015 Data) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Foreign Currency Rating | GDP per capita (USD) | Real GDP growth (%) | General Government Balance / GDP (%) | Net General Government Debt / GDP (%) | Current Account Balance / GDP (%) | Narrow Net External Debt / CAR (%) | |||||||||

| Aruba | BBB+ | 25,446.9 | 2.3 | -2.59 | 23.5 | -4.83 | 24.03 | |||||||||

| Australia | AAA | 56,244.6 | 2.42 | -2.88 | 18.44 | -3.55 | 269.15 | |||||||||

| Austria | AA+ | 43,347.3 | 0.6 | -2.2 | 81.19 | 1.72 | 124.01 | |||||||||

| Bahamas | BBB- | 23,316.1 | 1.3 | -2.16 | 50.96 | -18.99 | 47.61 | |||||||||

| Bangladesh | BB- | 1,253.7 | 6.4 | -3.4 | 24.02 | 0.6 | 8.5 | |||||||||

| Barbados | B | 15,510.9 | 1.2 | -4.73 | 86.47 | -2.96 | 33.96 | |||||||||

| Bermuda | A+ | 93,172.4 | 0.25 | -3.82 | -3.82 | 17.32 | -211.04 | |||||||||

| Brazil | BB+ | 8,551.6 | -2.5 | -8.06 | 53.52 | -3.72 | 27.01 | |||||||||

| China | AA- | 7,879.7 | 6.82 | -1.6 | 19.64 | 4.48 | -125.7 | |||||||||

| Colombia | BBB | 6,225.3 | 2.5 | -2.7 | 33.66 | -6.18 | 71.61 | |||||||||

| Czech Republic | AA- | 17,512.3 | 3.6 | -2 | 38.51 | 0.96 | 21.07 | |||||||||

| Dominican Republic | BB- | 6,766.9 | 5 | -4.24 | 41.76 | -0.89 | 81.11 | |||||||||

| Fiji | B+ | 4,934.6 | 2.5 | -2.7 | 43.95 | -9.25 | 14.43 | |||||||||

| France | AA | 36,339.7 | 1.1 | -3.8 | 88.53 | -1.22 | 195.94 | |||||||||

| Germany | AAA | 41,223.8 | 1.7 | -0.05 | 67.99 | 7.31 | 66.79 | |||||||||

| Guatemala | BB | 3,888.9 | 3.7 | -1.97 | 17.28 | -1.84 | 31.37 | |||||||||

| Honduras | B+ | 2,227.6 | 3.4 | -4.21 | 34.46 | -7.04 | 20.28 | |||||||||

| Hong Kong | AAA | 42,349.2 | 2.47 | 1.5 | -34.6 | 3.15 | -51.37 | |||||||||

| Hungary | BB+ | 12,329.4 | 3 | -2.6 | 71.63 | 4.59 | 42.05 | |||||||||

| India | BBB- | 1,684.6 | 7.4 | -7.1 | 66.83 | -1.39 | 20.09 | |||||||||

| Indonesia | BB+ | 3,406.4 | 4.9 | -2.3 | 22.93 | -2.6 | 64.22 | |||||||||

| Jamaica | B | 4,961.8 | 1.2 | -0.34 | 115.49 | -2.99 | 131.5 | |||||||||

| Japan | A+ | 33,077.9 | 1.21 | -5.8 | 127.93 | 2.68 | 19.4 | |||||||||

| Korea | AA- | 27,346.0 | 2.69 | 0.1 | 20.41 | 7.78 | -34.62 | |||||||||

| Mexico | BBB+ | 9,349.1 | 2.3 | -2.7 | 42.49 | -1.8 | 39.8 | |||||||||

| Mozambique | B- | 576.4 | 7 | -7 | 44.14 | -35.69 | 173.46 | |||||||||

| Netherlands | AA+ | 44,570.7 | 1.87 | -2.1 | 64.27 | 10.5 | 211.05 | |||||||||

| New Zealand | AA | 40,827.8 | 2.95 | -1.94 | 21.75 | -3.45 | 163.94 | |||||||||

| Philippines | BBB | 2,942.3 | 5.57 | -0.8 | 25.82 | 5 | -25.88 | |||||||||

| Poland | A- | 13,216.6 | 3.5 | -2.97 | 47.44 | -0.91 | 55.37 | |||||||||

| South Africa | BBB- | 5,902.0 | 1.63 | -3.6 | 42.69 | -4.32 | 28.35 | |||||||||

| Sri Lanka | B+ | 4,151.7 | 5.5 | -5.9 | 72.57 | -2 | 121.7 | |||||||||

| Taiwan | AA- | 22,210.4 | 1.54 | -1.6 | 41.26 | 12.71 | -92.67 | |||||||||

| Thailand | BBB+ | 5,945.3 | 3.1 | -0.6 | 22.65 | 2.9 | -17.12 | |||||||||

| Trinidad and Tobago | A | 19,432.8 | 0.8 | -3.28 | 18.66 | 2.21 | -133.49 | |||||||||

| United States | AA+ | 56,008.4 | 2.53 | -4.16 | 79.11 | -2.28 | 330.63 | |||||||||

| Venezuela | CCC | 21,949.2 | -7 | -4.49 | 20.47 | -0.84 | 125.38 | |||||||||

| Vietnam | BB- | 2,220.9 | 6.2 | -4.1 | 46.43 | 5.59 | -0.32 | |||||||||

| Ratings data as of Nov. 19, 2015. CAR--Current account receipts. | ||||||||||||||||

Table 2

| 250-Year Tropical Cyclone, Net Rating Impact, And Contribution By Assessment (Without Climate Change) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution by assessment | ||||||||

| Foreign currency long-term rating | Damage (% of value) | Insurance coverage (% of assets) | Net rating impact | Economic | External | Fiscal | Debt | |

| Aruba | BBB+ | 5.10 | 10.00 | 2.86 | 0.40 | 0.93 | 1.06 | 0.48 |

| Australia | AAA | 0.14 | 70.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Bahamas | BBB- | 16.63 | 10.00 | 4.41 | 1.55 | 0.00 | 1.76 | 1.10 |

| Bangladesh | BB- | 8.57 | 5.00 | 2.19 | 0.31 | 0.96 | 0.48 | 0.44 |

| Barbados | B | 9.00 | 10.00 | 4.77 | 0.67 | 1.67 | 1.80 | 0.63 |

| Bermuda | A+ | 3.44 | 10.00 | 1.48 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.42 |

| China | AA- | 0.19 | 8.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Colombia | BBB- | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Dominican Republic | BB- | 5.59 | 5.00 | 2.53 | 0.38 | 0.97 | 0.67 | 0.51 |

| Fiji | B+ | 11.72 | 10.00 | 4.48 | 0.53 | 1.41 | 1.65 | 0.90 |

| Guatemala | BB | 4.32 | 7.00 | 1.40 | 0.16 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 0.32 |

| Honduras | B+ | 4.31 | 7.00 | 1.17 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.23 |

| Hong Kong | AAA | 0.54 | 15.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| India | BBB- | 0.21 | 5.00 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Indonesia | BB+ | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Jamaica | B | 10.96 | 10.00 | 3.94 | 0.50 | 1.43 | 1.87 | 0.14 |

| Japan | A+ | 0.14 | 60.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Korea | AA- | 0.15 | 30.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Mexico | BBB+ | 0.53 | 15.00 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Mozambique | B- | 0.32 | 5.00 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| New Zealand | AA | 0.04 | 70.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Philippines | BBB | 1.70 | 5.00 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| South Africa | BBB- | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Sri Lanka | B+ | 0.16 | 5.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Taiwan | AA- | 1.80 | 15.00 | 0.54 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.12 |

| Thailand | BBB+ | 0.77 | 5.00 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | A | 1.41 | 10.00 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.10 |

| United States | AA+ | 0.38 | 70.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Venezuela | CCC | 1.07 | 15.00 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Vietnam | BB- | 7.87 | 5.00 | 1.80 | 0.29 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.34 |

Table 3

| 250-Year Tropical Cyclone, Additional Rating Impact Due To Climate Change And Contribution By Assessment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional contribution by assessment | ||||||||

| Foreign currency long-term rating | Additional damage (% of value) | Insurance coverage (% of assets) | Additional rating impact | Economic | External | Fiscal | Debt | |

| Aruba | BBB+ | 0.56 | 10 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Australia | AAA | 0.02 | 70 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Bahamas | BBB- | 4.23 | 10 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Bangladesh | BB- | 0.86 | 5 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Barbados | B | 2.47 | 10 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Bermuda | A+ | 1.60 | 10 | 0.79 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.21 |

| China | AA- | 0.08 | 8 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Colombia | BBB- | 0.19 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Dominican Republic | BB- | 1.88 | 5 | 0.92 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.20 |

| Fiji | B+ | 0.44 | 10 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Guatemala | BB | 0.58 | 7 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Honduras | B+ | 0.70 | 7 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Hong Kong | AAA | 0.24 | 15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| India | BBB- | 0.02 | 5 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Indonesia | BB+ | 0.08 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Jamaica | B | 2.58 | 10 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| Japan | A+ | 0.09 | 60 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Korea | AA- | 0.06 | 30 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Mexico | BBB+ | 0.10 | 15 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Mozambique | B- | 0.00 | 5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| New Zealand | AA | 0.02 | 70 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Philippines | BBB | 0.76 | 5 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| South Africa | BBB- | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sri Lanka | B+ | 0.01 | 5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Taiwan | AA- | 0.77 | 15 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| Thailand | BBB+ | 0.15 | 5 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | A | 0.71 | 10 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.05 |

| United States | AA+ | 0.17 | 70 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Venezuela | CCC | 0.13 | 15 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Vietnam | BB- | 1.68 | 5 | 0.35 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.08 |

Table 4

| 250-Year Tropical Cyclone, Economic Impact (Without Climate Change) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deviation from baseline | ||||||||

| Foreign currency long-term rating | Damage (% of value) | Insurance coverage (% of assets) | GDP per capita (USD) | Net General Government Debt | General government balance (5-yr average) | Narrow Net External Debt | Current Account Balance (5-yr average) | |

| Aruba | BBB+ | 5.10 | 10 | -4.7 | 23.88 | -4.9 | 73.3 | -11.4 |

| Australia | AAA | 0.14 | 70 | -0.1 | 0.64 | -0.1 | 1.2 | -0.1 |

| Bahamas | BBB- | 16.63 | 10 | -19.1 | 109.02 | -20.3 | 421.4 | -23.9 |

| Bangladesh | BB- | 8.57 | 5 | -11.6 | 11.84 | -2.5 | 78.6 | -3.6 |

| Barbados | B | 9.00 | 10 | -9.0 | 54.03 | -10.1 | 162.9 | -14.1 |

| Bermuda | A+ | 3.44 | 10 | -3.1 | 16.02 | -3.4 | 2.8 | -2.1 |

| China | AA- | 0.19 | 8 | -0.3 | 0.50 | -0.1 | 3.7 | -0.2 |

| Colombia | BBB- | 0.66 | 0 | -1.1 | 2.71 | -0.6 | 16.6 | -0.5 |

| Dominican Republic | BB- | 5.59 | 5 | -8.7 | 18.06 | -3.6 | 73.4 | -3.9 |

| Fiji | B+ | 11.72 | 10 | -18.5 | 41.75 | -8.1 | 119.2 | -10.2 |

| Guatemala | BB | 4.32 | 7 | -6.3 | 8.85 | -1.8 | 44.8 | -2.7 |

| Honduras | B+ | 4.31 | 7 | -6.6 | 10.71 | -2.2 | 37.0 | -3.7 |

| Hong Kong | AAA | 0.54 | 15 | -0.4 | 1.70 | -0.4 | 6.3 | -3.0 |

| India | BBB- | 0.21 | 5 | -0.3 | 0.46 | -0.1 | 4.1 | -0.2 |

| Indonesia | BB+ | 0.54 | 0 | -0.8 | 1.10 | -0.2 | 10.5 | -0.4 |

| Jamaica | B | 10.96 | 10 | -19.0 | 57.47 | -9.4 | 122.6 | -10.2 |

| Japan | A+ | 0.14 | 60 | -0.1 | 0.77 | -0.1 | 1.2 | -0.2 |

| Korea | AA- | 0.15 | 30 | -0.2 | 0.56 | -0.1 | 1.9 | -0.3 |

| Mexico | BBB+ | 0.53 | 15 | -0.9 | 1.82 | -0.4 | 8.1 | -0.7 |

| Mozambique | B- | 0.32 | 5 | -0.5 | 0.55 | -0.1 | 13.1 | -0.5 |

| New Zealand | AA | 0.04 | 70 | 0.0 | 0.18 | 0.0 | 1.4 | -0.1 |

| Philippines | BBB | 1.70 | 5 | -2.5 | 3.71 | -0.8 | 14.7 | -1.2 |

| South Africa | BBB- | 0.23 | 0 | -0.4 | 0.90 | -0.2 | 5.1 | -0.3 |

| Sri Lanka | B+ | 0.16 | 5 | -0.2 | 0.30 | -0.1 | 3.1 | -0.2 |

| Taiwan | AA- | 1.80 | 15 | -2.8 | 7.11 | -1.4 | 8.6 | -2.1 |

| Thailand | BBB+ | 0.77 | 5 | -1.7 | 2.32 | -0.5 | 8.1 | -1.3 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | A | 1.41 | 10 | -2.4 | 6.32 | -1.3 | 10.9 | -1.4 |

| United States | AA+ | 0.38 | 70 | -0.1 | 1.39 | -0.3 | 0.4 | -0.2 |

| Venezuela | CCC | 1.07 | 15 | -1.0 | 0.71 | -0.3 | 25.4 | -0.1 |

| Vietnam | BB- | 7.87 | 5 | -8.7 | 18.43 | -4.3 | 43.6 | -7.0 |

Table 5

| 250-Year Tropical Cyclone, Additional Economic Impact Due To Climate Change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional impact (%) | ||||||||

| Foreign currency long-term rating | Additional Damage (% of value) | Insurance coverage (% of assets) | GDP per capita (USD) | Net General Government Debt | General government balance (5-yr average) | Narrow Net External Debt | Current Account Balance (5-yr average) | |

| Aruba | BBB+ | 0.56 | 10 | -0.6 | 2.9 | -0.6 | 8.7 | -1.3 |

| Australia | AAA | 0.02 | 70 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Bahamas | BBB- | 4.23 | 10 | -6.2 | 42.3 | -7.5 | 158.8 | -7.6 |

| Bangladesh | BB- | 0.86 | 5 | -1.3 | 1.5 | -0.3 | 8.4 | -0.4 |

| Barbados | B | 2.47 | 10 | -3.0 | 18.7 | -3.4 | 53.8 | -4.2 |

| Bermuda | A+ | 1.60 | 10 | -1.6 | 8.0 | -1.7 | 0.8 | -1.0 |

| China | AA- | 0.08 | 8 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.9 | -0.1 |

| Colombia | BBB- | 0.19 | 0 | -0.3 | 0.8 | -0.2 | 4.3 | -0.1 |

| Dominican Republic | BB- | 1.88 | 5 | -3.2 | 7.1 | -1.4 | 26.2 | -1.4 |

| Fiji | B+ | 0.44 | 10 | -0.6 | 2.0 | -0.4 | 4.2 | -0.3 |

| Guatemala | BB | 0.58 | 7 | -0.9 | 1.3 | -0.3 | 5.9 | -0.4 |

| Honduras | B+ | 0.70 | 7 | -1.1 | 1.9 | -0.4 | 5.6 | -0.5 |

| Hong Kong | AAA | 0.24 | 15 | -0.2 | 0.8 | -0.2 | 2.2 | -1.0 |

| India | BBB- | 0.02 | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Indonesia | BB+ | 0.08 | 0 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 |

| Jamaica | B | 2.58 | 10 | -4.4 | 18.0 | -2.9 | 26.7 | -2.3 |

| Japan | A+ | 0.09 | 60 | -0.1 | 0.5 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| Korea | AA- | 0.06 | 30 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | -0.1 |

| Mexico | BBB+ | 0.10 | 15 | -0.2 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 1.3 | -0.1 |

| Mozambique | B- | 0.00 | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| New Zealand | AA | 0.02 | 70 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Philippines | BBB | 0.76 | 5 | -1.1 | 1.7 | -0.4 | 6.1 | -0.5 |

| South Africa | BBB- | 0.01 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Sri Lanka | B+ | 0.01 | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Taiwan | AA- | 0.77 | 15 | -1.2 | 3.2 | -0.6 | 3.0 | -0.8 |

| Thailand | BBB+ | 0.15 | 5 | -0.3 | 0.5 | -0.1 | 1.3 | -0.2 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | A | 0.71 | 10 | -1.2 | 3.3 | -0.7 | 5.0 | -0.7 |

| United States | AA+ | 0.17 | 70 | 0.0 | 0.6 | -0.1 | -0.3 | 0.0 |

| Venezuela | CCC | 0.13 | 15 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 0.0 |

| Vietnam | BB- | 1.68 | 5 | -0.4 | 4.3 | -1.1 | 4.0 | -0.7 |

Table 6

| 250-Year Flood, Net Rating Impact, And Contribution By Assessment (Without Climate Change) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution by assessment | ||||||||||||||||||

| Foreign currency long-term rating | Damage (% of value) | Insurance coverage (% of assets) | Net rating impact | Economic | External | Fiscal | Debt | |||||||||||

| Austria | AA+ | 0.14 | 35 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Brazil | BB+ | 0.53 | 10 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.07 | ||||||||||

| Czech Republic | AA- | 0.60 | 50 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.04 | ||||||||||

| France | AA | 0.24 | 80 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| Germany | AAA | 0.39 | 25 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Guatemala | BB | 0.13 | 7 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Honduras | B+ | 0.20 | 7 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Hungary | BB+ | 1.39 | 10 | 0.67 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.14 | ||||||||||

| Mozambique | B- | 0.11 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Netherlands | AA+ | 0.70 | 0 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.06 | ||||||||||

| Poland | A+ | 0.34 | 60 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| Sri Lanka | B+ | 0.36 | 5 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| Thailand | BBB+ | 4.31 | 10 | 1.62 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.25 | ||||||||||

| Venezuela | CCC | 0.32 | 15 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Ratings data as of Nov. 19, 2015. | ||||||||||||||||||

Table 7

| 250-Year Flood, Additional Rating Impact Due To Climate Change, And Contribution By Assessment | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional contribution by assessment | ||||||||||||||||||

| Foreign currency long-term rating | Additional Damage (% of value) | Insurance coverage (% of assets) | Additional rating impact | Economic | External | Fiscal | Debt | |||||||||||

| Austria | AA+ | 0.00 | 35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Brazil | BB+ | 0.41 | 10 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.06 | ||||||||||

| Czech Republic | AA- | (0.03) | 50 | -0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.01 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| France | AA | 0.03 | 80 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Germany | AAA | 0.01 | 25 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Guatemala | BB | 0.06 | 7 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Honduras | B+ | 0.12 | 7 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Hungary | BB+ | 0.10 | 10 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Mozambique | B- | 0.11 | 3 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Netherlands | AA+ | 0.07 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Poland | A+ | (0.01) | 60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Sri Lanka | B+ | 0.17 | 5 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Thailand | BBB+ | 4.34 | 10 | 1.79 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 0.30 | ||||||||||

| Venezuela | CCC | 0.13 | 15 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Ratings data as of Nov. 19, 2015. | ||||||||||||||||||

Table 8

| 250-Year Flood, Economic Impact (Without Climate Change) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deviation from baseline | ||||||||||||||||||

| Foreign currency long-term rating | Damage (% of value) | Insurance coverage (% of assets) | GDP per capita (USD) | Net General Government Debt | General government balance (5-yr average) | Narrow Net External Debt | Current Account Balance (5-yr average) | |||||||||||

| Austria | AA+ | 0.14 | 35 | -0.1 | 0.84 | -0.2 | 2.8 | -0.4 | ||||||||||

| Brazil | BB+ | 0.53 | 10 | -0.4 | 2.72 | -0.6 | 18.4 | -0.4 | ||||||||||

| Czech Republic | AA- | 0.60 | 50 | -0.4 | 2.78 | -0.6 | 3.1 | -0.8 | ||||||||||

| France | AA | 0.24 | 80 | 0.0 | 1.15 | -0.2 | 1.1 | -0.3 | ||||||||||

| Germany | AAA | 0.39 | 25 | -0.3 | 2.22 | -0.4 | 4.3 | -0.6 | ||||||||||

| Guatemala | BB | 0.13 | 7 | -0.2 | 0.25 | -0.1 | 2.7 | -0.2 | ||||||||||

| Honduras | B+ | 0.20 | 7 | -0.2 | 0.43 | -0.1 | 2.8 | -0.3 | ||||||||||

| Hungary | BB+ | 1.39 | 10 | -2.1 | 8.15 | -1.6 | 11.6 | -2.1 | ||||||||||

| Mozambique | B- | 0.11 | 3 | -0.2 | 0.18 | 0.0 | 6.6 | -0.4 | ||||||||||

| Netherlands | AA+ | 0.70 | 0 | -0.7 | 4.47 | -0.9 | 8.3 | -1.6 | ||||||||||

| Poland | A+ | 0.34 | 60 | -0.4 | 1.33 | -0.3 | 3.4 | -0.5 | ||||||||||

| Sri Lanka | B+ | 0.36 | 5 | -0.5 | 0.68 | -0.1 | 5.3 | -0.3 | ||||||||||

| Thailand | BBB+ | 4.31 | 10 | -9.2 | 13.72 | -3.0 | 39.0 | -6.5 | ||||||||||

| Venezuela | CCC | 0.32 | 15 | -0.3 | 0.21 | -0.1 | 8.7 | -0.1 | ||||||||||

| Ratings data as of Nov. 19, 2015. | ||||||||||||||||||

Table 9

| 250-Year Flood, Additional Economic Impact Due To Climate Change | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional impact (%) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Foreign currency long-term rating | Additional Damage (% of value) | Insurance coverage (% of assets) | GDP per capita (USD) | Net General Government Debt | General government balance (5-yr average) | Narrow Net External Debt | Current Account Balance (5-yr average) | |||||||||||

| Austria | AA+ | 0.00 | 35 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| Brazil | BB+ | 0.41 | 10 | -0.4 | 2.1 | -0.5 | 12.6 | -0.3 | ||||||||||

| Czech Republic | AA- | (0.03) | 50 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| France | AA | 0.03 | 80 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| Germany | AAA | 0.01 | 25 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| Guatemala | BB | 0.06 | 7 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| Honduras | B+ | 0.12 | 7 | -0.2 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 1.0 | -0.1 | ||||||||||

| Hungary | BB+ | 0.10 | 10 | -0.2 | 0.6 | -0.1 | 0.8 | -0.1 | ||||||||||

| Mozambique | B- | 0.11 | 3 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 3.4 | -0.1 | ||||||||||

| Netherlands | AA+ | 0.07 | 0 | -0.1 | 0.4 | -0.1 | 0.7 | -0.1 | ||||||||||

| Poland | A+ | (0.01) | 60 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| Sri Lanka | B+ | 0.17 | 5 | -0.2 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 1.9 | -0.1 | ||||||||||

| Thailand | BBB+ | 4.34 | 10 | -8.5 | 16.5 | -3.5 | 37.1 | -6.2 | ||||||||||

| Venezuela | CCC | 0.13 | 15 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| Ratings data as of Nov. 19, 2015. | ||||||||||||||||||

Appendix: Climate Change Impact Scenarios

Storms and floods are major natural hazards. Over the last decade they have been responsible for three-quarters of global insured losses and over half the fatalities and economic losses from all natural catastrophes. Most climate models suggest that the proportion of rainfall classified as heavy will continue to increase, raising the frequency and magnitude of flooding events. Over the last three decades, the number and intensity of hurricanes have increased in the North Atlantic and Western Pacific Oceans, thanks to rising sea-surface temperatures (Maslin, 2014).

Tropical cyclones

Tropical cyclones form in six basins worldwide, the East Pacific, North Atlantic, South Indian Ocean, North Indian Ocean, West Pacific, and South Pacific. An increase of maximum wind speed in the basins between 1% and 5% and stable cyclone frequencies is used, based on the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (2014), Emanuel (2013), and Knutson et al. (2010; see table 10). Model simulations show robust results for increased precipitation associated with cyclones. As the water vapor content of the tropical atmosphere increases, the rainfall rates in tropical cyclones increase as well. The storm surge associated with tropical cyclones increases due to sea level rises in the different basins. For the purpose of the simulation, sea level rise data from the IPCC AR5 based on the high greenhouse gas emission scenario Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 are used. In an extreme climate change scenario, storm surge increases due to rising sea levels until 2050 range between +25 cm and +40 cm for the different basins (see table 10).

Table 10

| Impacts On Tropical Cyclone Frequency, Cyclone-Induced Rainfall, And Sea Level Rises In An Extreme Climate Change Scenario | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in cyclone intensity (including rainfall) until 2050 | Change in cyclone surge, due to sea level rise until 2050 (meters) | |||||

| North Atlantic | 5.00 | 0.4 | ||||

| East Pacific | 3.50 | 0.3 | ||||

| West Pacific | 3.50 | 0.35 | ||||

| South Pacific and South Indian Ocean | 1.00 | 0.35 | ||||

| North Indian Ocean | 1.00 | 0.25 | ||||

| Source: Knutson (2010). | ||||||

Floods

Climate change is projected to have different impacts on precipitation patterns in different parts of the world. Where climate change leads to higher precipitation events, river inundation zones will extend. In some regions, severe flood events can occur more often, for example, an event that on average occurs every 100 years could occur every 50 years in the future. As warmer air can take up more moisture, and therefore more water is available for precipitation and subsequent flooding, the global water cycle intensifies. An opposing phenomenon may lead to fewer peak flood events: With warmer temperatures, snowfall will be lower and so will be meltwater.

In an extensive research study conducted by the University of Tokyo, Hirabayashi et al. (2013), calculated the changing return period of a 100-year flood event on a global scale. This change of return period was applied for all evaluated countries, downscaled to a time horizon until 2050 and modified by a country-based natural hazard management resilience factor that is published and evaluated by the insurance company FM Global on a yearly basis. The FM Global resilience index reflects the capability of a country to prevent and manage natural disasters. In simple words, it refers to "preparedness." While economically well-developed countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and the Czech Republic already have strong natural hazard prevention measures in place, countries like Honduras or Venezuela do not appear that well prepared.

Estimating climate change's effect on precipitation in Europe, Rajczak et al. (2013) find two different patterns. While Southern Europe will see less precipitation, the north will have a substantial increase, defining a zone that moves south/northwards with seasonal patterns. This pattern includes countries like Austria, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands, and Poland. Even while mean rainfall decreases for Southern Europe, strong events--like a five-year return period precipitation event leading to inundation--will in general increase across most of Europe.

Overall, most countries will see a moderate increase in climate change-related flood risk. However, countries like Mozambique and Thailand will see a strong increase in flood damage. On the other hand, Eastern European countries like Poland and Czech Republic will even see a small decrease in flood-related damages (only considering climate change and not taking economic growth into account). It should be mentioned, that economic growth will have a strong influence on future flood damages, too.

Related Criteria And Research

Related Criteria

Sovereign Rating Methodology, Dec. 23, 2014

Related Research

Standard & Poor's

- Storm Alert: Natural Disasters Can Damage Sovereign Creditworthiness: Methodological Supplement, Sept. 24, 2015

- Storm Alert: Natural Disasters Can Damage Sovereign Creditworthiness, Sept. 10, 2015

- Assessing The Impact Of Natural Disasters On Sovereign Credit Ratings, June 14, 2010.

- 2014 Annual Sovereign Default Study And Rating Transitions, May 18, 2015

- Climate Change Is A Global Mega-Trend For Sovereign Risk, May 15, 2014

- Global Aging 2013: Rising To The Challenge, March 20, 2013

Other

- Bresch, D.: climada, the open source Nat Cat model: https://github.com/davidnbresch/climada, 2015

- ECA, 2009: Shaping Climate Resilient Development – A Framework For Decision-Making, www.swissre.com/eca

- Emanuel, 2013: Downscaling CMIP5 climate models shows increased tropical cyclone activity over the 21st century

- Hirabayashi et al. (2013): Global flood risk under climate change, Nature Climate Change

- International Monetary Fund: World Economic Outlook; Statistical Appendix, October 2015

- IPCC (2014): Fifth Assessment Report, 2014, Working Group 1

- Knutson et al., 2010: Tropical cyclones and climate change

- Maslin, M.: Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press, 2014

- McGuire, B.: Global Catastrophes: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press, 2014

- Pew Research Centre: Climate Change Seen as Top Global Threat; July 14, 2015

- Rajczak et al. (2013): Projections of extreme precipitation events in regional climate simulations for Europe and the Alpine Region, Journal of Geophysical Research

- World Economic Forum: Global Risks 2015; 10th Edition, Insights Report, 2015

We have determined, based solely on the developments described herein, that no rating actions are currently warranted. Only a rating committee may determine a rating action and, as these developments were not viewed as material to the ratings, neither they nor this report were reviewed by a rating committee.

| Primary Credit Analyst: | Marko Mrsnik, Madrid (34) 91-389-6953; marko.mrsnik@standardandpoors.com |

| Secondary Credit Analysts: | Moritz Kraemer, Frankfurt (49) 69-33-999-249; moritz.kraemer@standardandpoors.com |

| Alexander Petrov, London (44) 20-7176-7115; alexander.petrov@standardandpoors.com | |

| Senior Economist: | Boris S Glass, London +44-207-176-8420; boris.glass@standardandpoors.com |

| Additional Contact: | SovereignEurope; SovereignEurope@standardandpoors.com |

No content (including ratings, credit-related analyses and data, valuations, model, software or other application or output therefrom) or any part thereof (Content) may be modified, reverse engineered, reproduced or distributed in any form by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC or its affiliates (collectively, S&P). The Content shall not be used for any unlawful or unauthorized purposes. S&P and any third-party providers, as well as their directors, officers, shareholders, employees or agents (collectively S&P Parties) do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, timeliness or availability of the Content. S&P Parties are not responsible for any errors or omissions (negligent or otherwise), regardless of the cause, for the results obtained from the use of the Content, or for the security or maintenance of any data input by the user. The Content is provided on an “as is” basis. S&P PARTIES DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, ANY WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR USE, FREEDOM FROM BUGS, SOFTWARE ERRORS OR DEFECTS, THAT THE CONTENT’S FUNCTIONING WILL BE UNINTERRUPTED OR THAT THE CONTENT WILL OPERATE WITH ANY SOFTWARE OR HARDWARE CONFIGURATION. In no event shall S&P Parties be liable to any party for any direct, indirect, incidental, exemplary, compensatory, punitive, special or consequential damages, costs, expenses, legal fees, or losses (including, without limitation, lost income or lost profits and opportunity costs or losses caused by negligence) in connection with any use of the Content even if advised of the possibility of such damages.

Credit-related and other analyses, including ratings, and statements in the Content are statements of opinion as of the date they are expressed and not statements of fact. S&P’s opinions, analyses and rating acknowledgment decisions (described below) are not recommendations to purchase, hold, or sell any securities or to make any investment decisions, and do not address the suitability of any security. S&P assumes no obligation to update the Content following publication in any form or format. The Content should not be relied on and is not a substitute for the skill, judgment and experience of the user, its management, employees, advisors and/or clients when making investment and other business decisions. S&P does not act as a fiduciary or an investment advisor except where registered as such. While S&P has obtained information from sources it believes to be reliable, S&P does not perform an audit and undertakes no duty of due diligence or independent verification of any information it receives. Rating-related publications may be published for a variety of reasons that are not necessarily dependent on action by rating committees, including, but not limited to, the publication of a periodic update on a credit rating and related analyses.

To the extent that regulatory authorities allow a rating agency to acknowledge in one jurisdiction a rating issued in another jurisdiction for certain regulatory purposes, S&P reserves the right to assign, withdraw or suspend such acknowledgment at any time and in its sole discretion. S&P Parties disclaim any duty whatsoever arising out of the assignment, withdrawal or suspension of an acknowledgment as well as any liability for any damage alleged to have been suffered on account thereof.

S&P keeps certain activities of its business units separate from each other in order to preserve the independence and objectivity of their respective activities. As a result, certain business units of S&P may have information that is not available to other S&P business units. S&P has established policies and procedures to maintain the confidentiality of certain non-public information received in connection with each analytical process.

S&P may receive compensation for its ratings and certain analyses, normally from issuers or underwriters of securities or from obligors. S&P reserves the right to disseminate its opinions and analyses. S&P's public ratings and analyses are made available on its Web sites, www.standardandpoors.com (free of charge), and www.ratingsdirect.com and www.globalcreditportal.com (subscription), and may be distributed through other means, including via S&P publications and third-party redistributors. Additional information about our ratings fees is available at www.standardandpoors.com/usratingsfees.

Any Passwords/user IDs issued by S&P to users are single user-dedicated and may ONLY be used by the individual to whom they have been assigned. No sharing of passwords/user IDs and no simultaneous access via the same password/user ID is permitted. To reprint, translate, or use the data or information other than as provided herein, contact S&P Global Ratings, Client Services, 55 Water Street, New York, NY 10041; (1) 212-438-7280 or by e-mail to: research_request@spglobal.com.