Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Research — 10 May, 2022

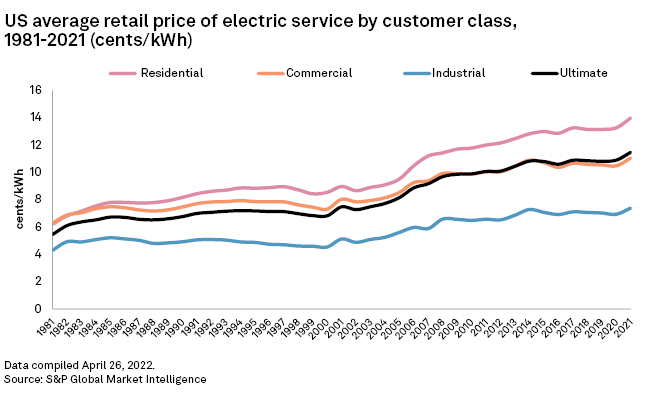

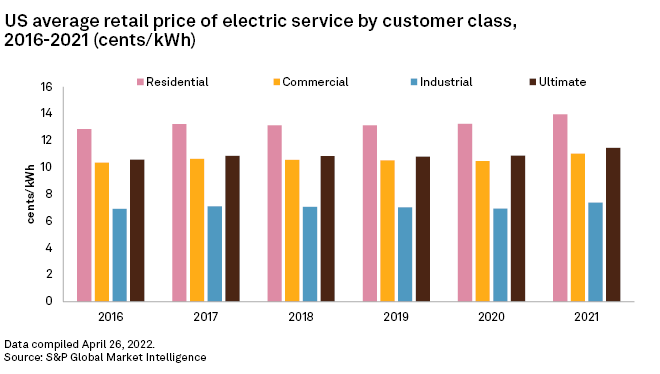

The average retail price of electricity per kilowatt-hour paid by ultimate customers in the U.S. in 2021 rose 5.24% on a nominal basis to 11.45 cents. The observed increase in price per kilowatt-hour was consistent across residential, commercial and industrial customer classes, according to bundled electric sales data gathered and analyzed by Regulatory Research Associates from information originally sourced from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

* The 2021 overall electric price at the ultimate customer level — an aggregate of the residential, commercial and industrial classes — rose 5.24% on a nominal basis, or 1.1% on a real basis.

* The higher real price in 2021 at the ultimate customer level marked the first time in three years that real prices had grown on an aggregate basis. All three customer classes recorded real increases in retail electricity prices in 2021.

* Considering heightened geopolitical risks and supply chain and raw materials issues in multiple industries, nominal and real retail electric prices will likely increase in 2022 across all customer classes. As measured by the consumer price index, inflation was 8.54% higher in March 2022 than in March 2021.

* Despite that natural gas may only contribute 35% of retail electricity in 2022, the price of gas has increased materially in 2022 for generators and has impacted costs. In addition, higher renewable infrastructure expenses for new projects will likely negatively impact the cost of electricity from renewable sources.

The 2021 overall electric price increase at the ultimate customer level — a category that forms an aggregate of the residential, commercial and industrial customer pricing data followed a 0.74% increase in retail electricity prices in 2020 and a 0.63% decrease in 2019.

Inflation-adjusted or real electric prices were also generally higher in 2021, with the average bundled price paid by ultimate customers up 1.1% in 2021, countering decreases that occurred in each of the three prior years, with prices falling 0.6% in 2020, 4.8% in 2019 and 2.7% in 2018.

Electric price growth restrained even with substantial infrastructure investment, generation evolution

Higher inflation that arose from various factors, including manufacturing and supply chain disruptions and pandemic-induced increases in raw materials costs, likely drove the substantial increase in 2021 average retail electricity prices.

Increased energy costs may have been the most influential factor in higher electric prices, as the cost of most energy commodities rose in 2021. Natural gas prices rose as producers could not match growth in gas utilization by multiple industries and from swelling LNG export activity. Producers have been increasingly focused on improving profitability and balance sheet strength rather than growth. Producers are responding now that multiple drivers support more production; by 2023, production increases may somewhat take the edge off gas prices. While U.S. dry gas production grew only 2.3% in 2021 to average 93.6 Bcf per day, the EIA expects production will average 97.4 Bcf per day in 2022 and 100.9 Bcf per day in 2023, representing 4.1% and 3.5% successive increases, respectively. Rising production is expected to help incrementally ease supply constraints and moderate prices.

Lower gas prices keep retail power prices in check

Upward pressure on customer rates before 2021 had been generally curbed despite substantial and ongoing infrastructure investment in the utility industry. Over the last decade, the expansion of shale gas and the attendant proliferation of natural gas-fired generation appear to have mitigated price pressures.

Yet in 2022, natural gas prices appear poised to persist at levels up to 50% higher than the 2021 average wholesale gas price, likely pressuring electricity prices in 2022 and 2023. While expected higher natural gas prices and state and federal tax investment incentives may provide additional impetus for expanding renewable generation, there remains substantial support in many regions for maintaining energy diversity and supporting the expansion of renewables with natural gas baseload power as the energy transition progresses.

Cost of Electricity

Notably, renewable energy has become a least-cost generation technology in some parts of the country, and renewable projects are generally less burdened with operational, regulatory and social risk factors than comparably sized new fossil generation resources.

2022 electricity costs likely higher with increased natural gas prices, ongoing supply chain disruptions

Electricity prices may incrementally rise as the price of natural gas increases on tighter supplies. The EIA forecasts amplified gas prices for the remainder of 2022 and much of 2023 driven by increased natural gas demand from LNG exports and growing gas use outside the power generation sphere. Along with improving commercial and economic environments, growing residential and industrial use may support higher gas prices. The EIA anticipates that the prevailing Henry Hub spot natural gas price in 2022 is likely to average $5.23 per MMBtu for the entire year, although it may subside to $4.01 per MMBtu, on average, for 2023 on the expectation of higher storage levels as natural gas production gradually increases.

Higher natural gas prices are expected to drive increased U.S. upstream gas development and production operations, potentially slowing rising gas prices by 2023. In mid-April summaries of its Short-term Energy Outlook, the EIA forecasts the natural gas delivered-price for power generators will eventually fall from an average of $5.85/MMBtu in the second quarter of 2022 to $4.21/MMBtu on average for 2023. The EIA's forecast for natural gas price easing may be premature, considering the present geopolitical upheaval in energy flows and costs due to the war in Ukraine.

The present cost of natural gas for power generation is already significantly higher than the average delivered price of $4.98/MMBtu in 2021 and $2.32/MMBtu in 2020. The EIA expects the higher gas prices and the growing contribution from the buildout of renewable generation to cause the share of natural gas in U.S. power generation to fall from 37% in 2021 to 35% in 2022 and 2023.

Increasing costs are also impacting renewable energy projects, and these may filter down to retail electric rates, with increased costs from fossil fuel and renewables causing upticks in retail electric prices in 2022 and 2023. Additionally, the wind industry is struggling with higher raw materials and transportation costs as well as technical issues that have impacted profitability and generated operating losses at some of the largest wind turbine manufacturers. Over the last several quarters, wind turbine manufacturers have been reworking their price structures and communicating to the utility industry that higher prices are necessary to preserve margins.

Historical electricity price trends

Over the last decade, real electricity prices for ultimate customers were down 6.8%. In addition to declining fuel prices, lower electricity prices in recent years have also been attributable to declining interest rates and the resultant drop in authorized equity returns at regulated utilities. Looking forward, the Federal Reserve, or Fed, has initiated plans to raise interest rates gradually in a bid to address inflation. In March, the Fed raised its benchmark short-term borrowing rate by 25 basis points for the first time in two years; then, in the first week of May, the Fed increased the rate by an additional 50 basis points. The last time the Fed raised its benchmark rate by the same magnitude was in 2000. The Fed may raise rates five more times in 2022 to tighten monetary policy and reduce the size of its balance sheet through incremental retirement of its sizable Treasury bond holdings, with the possibility that the Fed funds rate will approach 2% by the end of the year. Median projections indicate that the Fed may raise rates to 2.75% by the end of 2023, potentially reaching a level not observed since 2008.

Nominally, over the last decade, bundled electricity prices for residential, commercial and industrial customers were up 16.5%, 10.0% and 12.5%, respectively. On an inflation-adjusted basis, however, prices fell 4.0% for residential customers, 10.7% for commercial customers and 8.3% for industrial customers.

Electricity prices paid by ultimate customers vary widely on a geographic basis

Electric customers in Hawaii paid the highest ultimate prices in the country in 2021, at 30.35 cents/kWh. Other states with high average prices were Massachusetts at 22.19 cents/kWh and California at 21.41 cents/kWh. In 2021, Wyoming, Idaho and Utah observed the lowest prices, where the average ultimate customer paid 7.75 cents/kWh, 8.18 cents/kWh and 8.20 cents/kWh, respectively.

We note that retail competition for electric generation service exists in 22 state jurisdictions; in these states, the data presented in this study is for power sold to retail customers who have not selected an alternative or competitive power provider and continue to be served by the incumbent local distribution utility under state commission-approved standard-offer service rates.

Texas operates under a unique market structure, and standard-offer service does not exist. Rather than the incumbent utility, competitive electric providers serve all customers within the Electric Reliability Council of Texas at rates not regulated by the Texas Public Utility Commission. As a result, this report only incorporates Texas companies that have not restructured and continue to be traditionally regulated.

Historical perspective

Retail electric prices rose dramatically in the mid-1970s following the 1973 OPEC Oil Embargo and, except for 1979, continued to rise in real terms until 1984. From 1984 to 1994, with a few exceptions, nominal prices continued to increase each year, although in most cases at a lesser rate than inflation. From 1995 to 2000, prices declined in both nominal and real terms. RRA attributes this to the cessation of large, capital-intensive construction programs; the emergence of low-cost, natural-gas-fired combustion turbines to meet peak demand; competition in the form of energy conservation; rate freezes and caps mandated by electric restructuring activity; and reluctance on the part of utilities to seek rate increases when commissions were considering switching to a competitive framework.

In 2001, for the first time in roughly a decade, the average retail price of electricity rose in nominal and real terms, largely due to sharp increases in wholesale market prices and power supply shortages. From 2003 to 2009, prices rose steadily in nominal and real terms due to several factors, including the expiration of restructuring-related rate freezes and the associated implementation of competitive wholesale procurement in certain jurisdictions; rising natural gas prices — although this was significantly moderated in the wake of the 2008 economic downturn and by increasing shale-gas production; the costs associated with new transmission facilities and infrastructure investment; the beginning of a new construction cycle; increasing environmental compliance costs; and rising employee benefit and health care costs.

In 2010, prices rose slightly in nominal terms but fell moderately in real terms, a trend that continued through 2012. In 2013 and 2014, prices rose strongly in nominal and real terms, driven by aggressive utility capital spending plans that addressed system reliability, aging infrastructure, demand-side management, energy conservation, renewables and environmental issues. In 2015 and 2016, however, the price of electricity fell in nominal and real terms, reflecting further reductions in fuel expenses and market prices for standard-offer power and lower allowed rates of return. In 2017, that trend briefly reversed before the price of electricity fell again in 2018 and 2019 in nominal and real terms.

In 2020, the average nominal price of electricity rose incrementally, slightly under 1%, while on a real basis, prices fell slightly under half of one percent. In 2021, retail electric prices rose nominally and in real terms for the first time in three years. Several factors drove this dual increase spanning all three customer classes, including higher fuel costs for power generation, particularly regarding natural gas.

Regulatory Research Associates is a group within S&P Global Commodity Insights.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.