Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

16 Sep, 2021

By J. Holzman

|

U.S. House Natural Resources Chairman Raul Grijalva, D-Ariz., presides over a 2020 committee hearing. An advocate for hard-rock mining reform, Grijalva is pushing to include new royalty payments for miners as part of Democrats' sweeping reconciliation legislation. |

Democrats' sweeping climate stimulus package would impose royalties on U.S. hard-rock mining for the first time, and miners fear the fees would kill the domestic industry.

The U.S.' first-ever royalty fee on new and existing hard-rock mines on federal land would impose an 8% royalty on new mines and a 4% royalty on existing mines, both on gross income. It would also impose a "reclamation fee" of 7 cents per ton of material displaced from a mine site to pay for remediation work on abandoned mine lands.

Democrats see an opportunity to raise more revenue from the profits mining companies earn on rising commodity prices. The new fees would raise $2 billion over 10 years to help pay for mine cleanups, but the mining industry said the rates proposed in the bill are too high.

Imposing the mining royalties would be a matter of fairness, said U.S. House Natural Resources Chairman Raul Grijalva, D-Ariz., whose committee approved the language last week. Unlike oil, gas and coal operations on federal lands, hard-rock mines pay no royalties to the federal government under a mining law passed in 1872.

"There have been no royalties collected since the inception of the mining law. It's beyond antiquated," Grijalva said. "It's about raising revenue to be able to require the mining industry to make similar payments that other extractive industries pay for the use of public lands."

Democrats and a broad array of progressive groups have long sought to enact a royalty for hard-rock mines, but standalone legislation to overhaul federal mining statutes has failed to find enough support in both chambers of Congress to become law. Grijalva authored mining reform legislation in the past, but even those proposals that passed the U.S. House never received a vote in the U.S. Senate.

"Over the years, mining companies — many of which are foreign-owned — have deprived taxpayers and the federal treasury of billions of dollars," Jenn Rowland-Shea, Deputy Director for Public Lands at the left-leaning Center for American Progress, said in an email. "It's time for these companies to pay their fair share, and establishing a new royalty would end this subsidy and raise revenue."

Miners between a hard rock and a hard place

U.S. miners see the proposal as untenable.

"We have long said we are open to reasonable royalty proposals, but an 8 percent royalty is merely punitive," said Conor Bernstein, a spokesman for the National Mining Association, which represents major U.S. mining companies.

In January, the National Mining Association supported

"It would have a chilling effect, all but taking the U.S. out of the game in the race to stand up mineral production desperately needed to meet soaring demand coming from infrastructure reinvestment, the energy transition and the accelerating electric vehicle revolution," Bernstein said in an email.

Democrats are taking aim at miners' pocketbooks at a time when rising commodity prices and exploding profits are leading other governments to try and snag more revenue from producers. This trend recently made its way to Nevada and resulted in state legislators raising the state mining tax to help fill a budgetary gap created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Chile, too, is considering cranking up taxes on its copper miners.

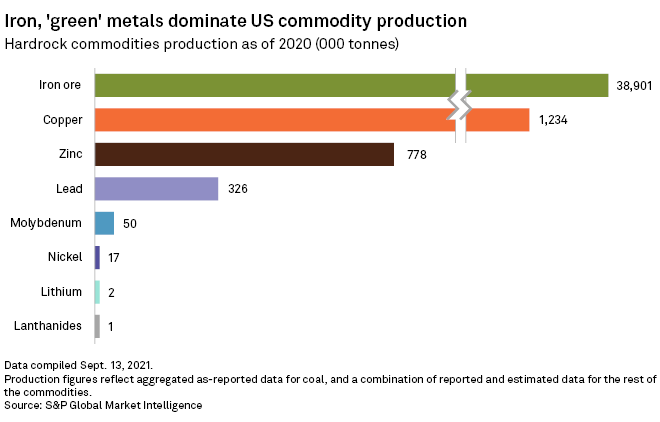

U.S. hard-rock mining is dominated by copper, zinc and iron ore, three of the minerals exposed to the current commodity bull market, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. The U.S. represents 6.0% of global copper production, 5.6% of global zinc production and 1.6% of global iron ore production.

The new rate could hinder investment in new U.S. mines, analysts said.

"[This is] a cost on mining that is badly out of the market and renders a lot of mining projects uneconomic. A lot of companies won't develop minerals in the United States," said Scot Anderson, a partner who represents mining companies at natural resources law firm Hogan Lovells.

Federal royalties could only avoid a negative impact on U.S. mining and metals companies if enacted in exchange for favorable legislation such as permitting reform, Michael Corelli, an analyst at Moody's Investors Service, told Market Intelligence.

"Clearly, any royalty is negative versus no royalties. Unless there is some kind of quid pro quo where they are going to charge royalties but give them a little more freedom with permitting," Corelli said.

The fight in Congress

The National Mining Association is exercising its lobbying muscle to oppose the royalty language, reaching out to lawmakers on a "broad and bipartisan" basis, Bernstein said.

But it is unclear whether it can win the vote of an influential Senate member: Sen. Joe Manchin from the coal-producing state of West Virginia and the chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Manchin already backs the principle of hard-rock mining reform, and while Manchin has other reservations about the bill as a whole, he said in 2019 that the existing no-royalty regime, "makes no sense to me at all." Manchin did not respond to requests for comment.

Grijalva said discussions between the House and the Senate won't begin until the House passes the bill, possibly as soon as this week.

And as for negotiations with miners, Grijalva, whose home state includes major copper mining operations, is ready to talk.

"The discussion is valid and I'm not one to close any door," the Arizona Democrat said.