Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

17 Mar, 2022

A jump in corporate borrowing costs tied to rising interest rates is unlikely to spark a new rush of bankruptcies and defaults this year.

As expected, the Federal Open Market Committee on March 16 raised the federal funds target rate — a benchmark for broader borrowing costs — by 25 basis points from its near 0% floor. Most Federal Reserve officials also believe interest rates will jump to nearly 2% before the end of the year as the central bank looks to combat historic inflation.

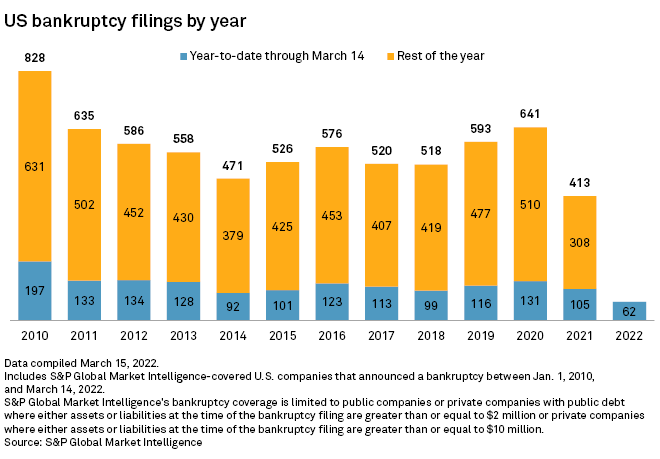

Although those moves will pressure companies struggling to stay afloat, they still have ample options to avoid turning to court or missing a debt payment. Corporate bankruptcies hit a 12-year low in 2021 and so far, 2022 is not showing any signs of a jump. Defaults are also slowing, with six rated companies so far this year compared to 13 at the same point in 2021 and 2022's default rate will fall below pre-pandemic figures, according to S&P Global Ratings.

Interest rates above the Fed's anticipated hikes would add extra pressure that would force more companies to default or go bankrupt, analysts said. Absent that, however, companies continue to reap the benefits of lingering pandemic stimulus and generous lenders that have so far kept them solvent.

"Slow to moderate rate increases should have limited impacts on corporate survival," said Joel Naroff, president of Naroff Economics. "If a company cannot pay one percentage point more in interest expenses, which is what is likely to happen over the rest of the year, their problems are a lot greater than debt payments."

Fed watch

Nearly 90% of investors as of March 16 expected the Fed will raise interest rates at least six more times in 2022, according to the CME FedWatch Tool, a measure of investor expectations for the Fed Funds target rate. That would push the target federal funds rate to at least 1.75%. Projections released by the Fed on March 16 show expectations of rates going even higher in 2023.

Rate hikes are needed because inflation is becoming more embedded in the economy, Naroff said. Consumer prices jumped 7.9% year over year in February, the fastest increase in about 40 years.

"The Fed is boxed in," Naroff said. "It needs to reduce inflation just as external events over which it has no control are raising inflation and risking growth."

The slowdown in bankruptcies in 2021 came as companies reaped the benefits of government stimulus and easy lending conditions from creditors looking to avoid defaults. Shifting Fed policy, including rising interest rates, poses a threat to heavily indebted companies that will face higher costs to borrow and refinance.

Historically, though, rate hikes up to 2% have not prompted a rise in corporate filings, said Aaron Hammer, chair of HMB's bankruptcy, reorganization and creditors' rights practice.

"I would expect that the Federal funds rate would have to be higher than at least 3% to 4% in order to see a noticeable impact," Hammer said.

The shift in business and consumer demand from the pandemic might send more companies to courts in 2022. Businesses built around pre-pandemic work conditions, such as commercial real estate, might need to look into bankruptcy solutions.

To default or not

Another factor keeping new business failures low is that many loans have a higher floor above the Fed's target rate so companies are paying higher interest on their loans already.

About 60% of leveraged loans have a floor of 50 to 100 basis points, according to Ramki Muthukrishnan, head of leveraged finance at S&P Global Ratings.

Ratings predicts the trailing 12-month default ratio for speculative-grade companies to reach 3% by December 2022. That is below the pre-pandemic level of 3.2% in January 2020.

The "three-legged stool" of defaults — economic story, credit story, and markets and financing conditions — are still very supportive, meaning the risk of defaults is low, said Nick Kraemer, head of ratings performance analytics at Ratings.

Above-trend economic growth as consumers continue to spend despite rising prices, an increase in speculative-grade upgrades in 2021, and good financing conditions all contribute to keeping defaults low, Kraemer said.

Defaults slowed during the COVID-19 pandemic, but interest rates and projected default rates are looking more like the end of 2019, Kraemer said. The Fed lowered the target range for interest rates to 1.5%-1.75% before dropping rates to near 0% when the pandemic took hold.

"So, there's some worry out there, but I don't think it’s going to translate into a big spike in defaults by the end of the year," Kraemer said.