S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial Institutions

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial Institutions

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

14 Dec, 2021

By Bill Holland and Susan Dlin

| Flames from a flaring pit near a well in the Bakken oil field in North Dakota. The primary component of natural gas is methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Source: Orjan F. Ellingvag/Corbis News via Getty Images |

While most major U.S. and European oil and gas companies have pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, there is wide disagreement over what net-zero means and little agreement inside or outside the industry about how to get there.

|

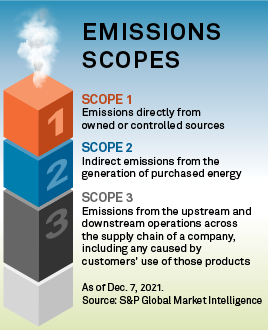

The number of major oil and gas operators pledging to hit net-zero emissions from their company's operations and supply chains, known as Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, increased from 50% to 70% over the past six months, according to reports from 30 companies compiled by S&P Global Market Intelligence in November. Net-zero carbon goals are needed to bring industries into alignment with the targets of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

But the industry needs to cut emissions sharply to meet a critical goal of the agreement — limiting global warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius by 2050. According to calculations by S&P Global Trucost's climate risk assessment unit, the oil and gas industry is on track to emit carbon in line with a rise of over 5 degrees in global temperatures through 2025.

Major oil and gas upstream and midstream companies have been quick to set goals, but few have concrete emissions goals until after 2025, raising questions as to how an industry that is projected to dump millions of tons of carbon dioxide equivalent into the atmosphere can reverse that flow in time to meet the 2 degrees or less target of the Paris climate accord.

The world's top oil and gas companies must embrace the ongoing energy transition, invest in cleaner solutions and profit as a result or face financial failure if they stand pat, U.S. Deputy Energy Secretary David Turk said at the 23rd World Petroleum Congress in Houston.

"I don't think we're going to be successful unless major companies step up and are part of solution," Turk said Dec. 6, noting that some companies will and some will not. "We cannot delude ourselves."

Continental divides

Details in the net-zero pledges reveal a split between European oil and gas producers and their American counterparts over strategies and tactics, even as both groups come under investor and legal pressure to cut carbon emissions.

The European companies have started cutting the intensity of their carbon emissions by selling off noncore fossil fuel operations and buying renewable energy projects and companies. Critics say that tactic does not cut emissions; it just makes those emissions somebody else's problem.

The U.S., on the other hand, has doubled down on the oil and gas business, betting that technology and taxes are the route to lower carbon emissions.

Either approach could work, according to Daniel Raimi, director of Washington, D.C.-based think tank Resources for the Future's Equity in the Energy Transition Initiative project. "I would start diversifying investments today to develop expertise in emerging technologies," Raimi said, which is the European path. "That's not the specialty of most oil and gas companies."

Investments in climate-adjacent technologies, such as carbon capture and storage and offshore wind development, play to American oil producers' strengths in construction and engineering, Raimi said.

|

The trans-Atlantic rivals are split on the issue of who should bear the burden of reducing Scope 3 emissions, or emissions made by consumers of oil and gas. Is Exxon Mobil Corp. or BP PLC accountable for the carbon generated from gas-powered automobiles, or is the driver of the car that burned the fuel responsible?

Most in the European group are taking accountability for the entire life cycle of the product, meaning Scopes 1, 2 and 3. The Americans are not.

Tackling user emissions

Although U.S. oil and gas producers are researching ways to lower the carbon content of their products, U.S. operators think the fastest way to shape behavior and lower emissions is to put some costs on the consumer through an economy-wide carbon tax.

"This is the most significant, impactful and transparent way that public policy can incentivize the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions associated with the use of oil and gas products," said Aaron Padilla, director of climate and environmental, social and governance policy at the industry's major trade group, the American Petroleum Institute. "That's the best way to think of our industry's approach to Scope 3."

That was one of the takeaways of the COP26 conference, said Pavel Molchanov, renewables and oil and gas analyst at Raymond James & Associates. "From an investing standpoint, the key takeaway is that carbon pricing will need to continue escalating for there to be any chance of preventing global heating from topping 2 degrees," Molchanov said in a recap of the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions are not critical for investors, but Scope 3 emissions are, according to Axel Dalman, an analyst at Carbon Tracker, a London-based think tank devoted to exploring the impacts of climate change on financial markets.

"You've got to look at how they're addressing Scope 3 emissions," Dalman said, "because that ties into how they plan to make their business more resilient in a world that doesn't need their products anymore."

Trucost is part of S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Methodology note: Trucost's Paris Alignment data adopts a physical intensity-based Sectoral Decarbonization Approach and an economic intensity-based Greenhouse gas Emissions per unit of Value Added approach consistent with Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures guidance and European Union Paris Aligned Benchmark requirements to examine the adequacy of emissions reductions over time in meeting 1.5-degree C or 2-degree C carbon budgets. The assessment incorporates both historical Scope 1 and 2 emissions as well as forward-looking indicators such as targets disclosed to the CDP over a medium-term horizon through to 2025. Trucost's latest update incorporates historical data up to 2019, the last full year before energy use plunged during the COVID-19 pandemic.