S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

27 Jul, 2021

By Sam Clark and Darakhshan Nazir

As Europe's major cloud providers seek to future-proof their server capacity amid surging demand, data center investment in the region is reaching record highs.

In the first three months of 2021, data center operators sold 92 MW of power in Frankfurt, London, Amsterdam and Paris, making it the highest quarter on record, according to data from real estate consultancy CBRE. This is just under half the 201 MW sold in 2020, the full-year record.

The four cities, often abbreviated as FLAP, are considered Europe's data center hubs — but this could be about to change, according to analysts. A potential tightening of data protection rules, coupled with sheer demand from cloud providers, means growth in less established markets could outpace that in FLAP.

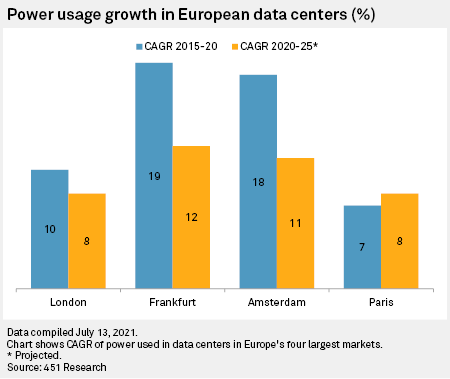

Dublin, Zurich and Madrid, for example, will grow faster between 2020-2025 than FLAP, data from 451 Research, a part of S&P Global Market Intelligence, shows. This is partly because growth in traditional markets will slow; Frankfurt, for example, is expected to see power usage CAGR fall to 12% between 2020 and 2025, from 19% in 2015-2020.

"The safest assumption is that data centers will be everywhere," said Marcus de Minckwitz, a director at real estate company Savills.

Driving demand

Cloud companies accounted for 92% of first-quarter power take-up, according to CBRE. Amazon.com Inc.'s Web Services, Microsoft Corp.'s Azure and Alphabet Inc.'s Google Cloud Platform are the three largest cloud providers. These "hyperscalers" are behind the largest data center leasing deals.

The pandemic is behind some of the growth, as accelerated digitization and remote working amid boosted demand, analysts said. As a result, investors see data centers as an increasingly safe bet, said Rahiel Nasir, an analyst at 451 Research.

"COVID-19 has really brought it into sharp relief," Nasir said. "The role of the data center as essential infrastructure has been highlighted during the pandemic as people have had to lean more on digital services."

A lesser factor driving demand is the possibility that the European Union will introduce stricter data protection rules, namely an obligation on companies to store and process data within the EU.

Residency requirements came to the fore in 2018 with the enforcement of the EU's General Data Protection Regulation, as well as a European Court of Justice ruling last July which cast doubt on whether personal data could be transferred abroad — leading some companies to consider local data storage for compliance reasons.

Amazon Web Services, or AWS, said in June when launching a cluster of data centers in Spain that the move will allow local companies to "securely store their content in Spain with the assurance that they will retain complete control over the location of their data, while providing even lower latency to end users across the country." Latency refers to how long it takes for data to travel between two locations.

As well as being able to offer lower latency, cloud providers are motivated to have a local presence because it improves their chances of winning business, said Penny Madsen-Jones, a director at CBRE. "Businesses tend to do better when they have local teams," Madsen-Jones said. "There's also an emphasis on partnerships. How well the hyperscalers do sometimes depends on how well they do on the ground."

New markets

The same factors are pushing cloud providers into "second-tier" markets, which are European cities with some existing data center infrastructure but less than in FLAP cities. Second-tier cities include Dublin, Milan, Berlin, Zurich and Madrid.

In Milan, for example, approximately 104 MW of power is expected to be added between 2020 and 2025 on top of the existing 155 MW, according to data from 451 Research. The Italian city experienced a 14% CAGR between 2015 and 2020 and is expected to witness 11% growth between 2020 and 2025.

Forecasting where demand will be greatest is a challenge for hyperscalers. Within the context of emerging markets such as Africa and the Middle East, some indicators include attractive digital economy policies set out by national governments and a strong startup economy, Nasir from 451 Research said.

Expansions are also complicated by lead times of up to two years, de Minckwitz said.

Cloud providers are unlikely to be deterred, according to Madsen-Jones.

"They will end up having a presence in every country where they've got customers because they have got to future-proof these investments. They don't know what data residency requirements will arise, and there's also latency requirements," Madsen-Jones said.