S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

14 Jun, 2021

By Anna Akins and David DiMolfetta

A historic — and complicated — deal aimed at setting a global minimum tax rate would mean a bigger tax bill for most publicly traded U.S. tech firms if passed into law.

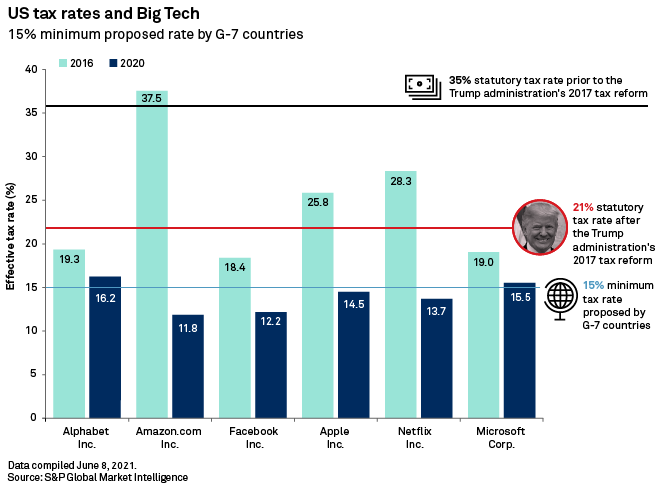

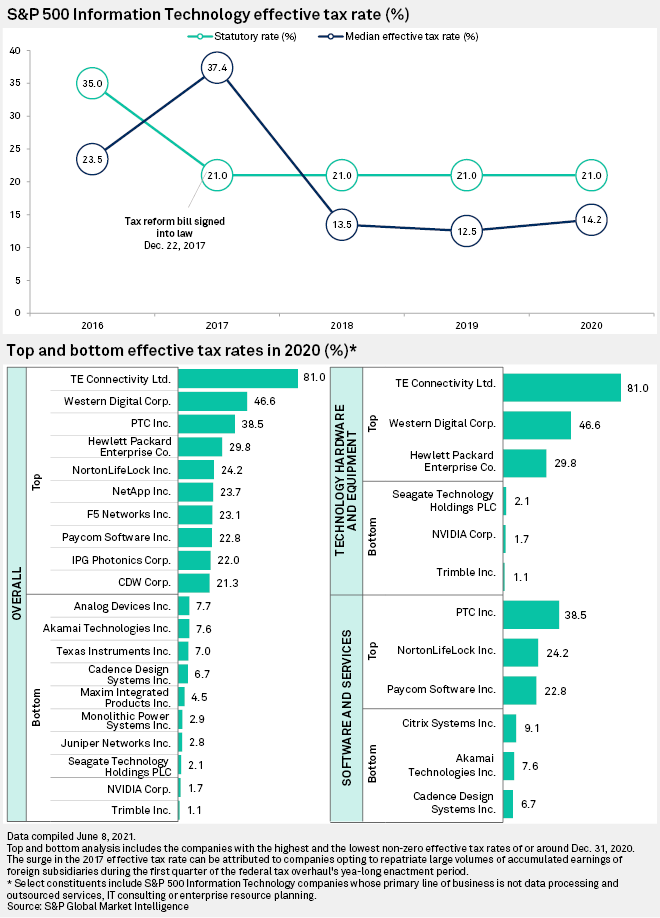

Among select S&P 500 Information Technology companies, a majority are already paying lower taxes than the current 21% statutory corporate tax rate established by U.S. former President Donald Trump. The companies' tax rates are also lower than the 15% minimum global tax recently backed by G-7 finance ministers from the United States, the U.K., Canada, France, Germany, Italy and Japan.

Information technology companies in the S&P 500 reported a median effective tax rate of 14.2% for 2020, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. But several notable Big Tech names like Facebook Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. have effective rates even lower than that. Those companies, along with others like Alphabet Inc. and Microsoft Corp. are facing harsh criticism for shoring their profits in low-tax countries and the way they account for tax breaks to minimize their bill.

"We ... recognize this could mean Facebook paying more tax, and in different places," Nick Clegg, Facebook's vice president of global affairs, said in a June 5 tweet after the G-7 agreement. Nevertheless, Clegg said Facebook supports international tax reform.

Big Tech

Looking at the tech industry's titans, Amazon and Facebook have two of the lowest effective tax rates of the bunch. Amazon's stood at 11.8% and Facebook at 12.2% in 2020, based on Market Intelligence data. Netflix Inc. had an effective tax rate of 13.7%. But a couple of companies actually have effective tax rates that are higher than the 15% minimum global tax being proposed. Microsoft and Alphabet reported effective tax rates last year of 15.5% and 16.2%, respectively.

Amazon is perhaps the most commonly cited tech company that has historically paid a low tax rate. It became a target for politicians — both Democrats and Republicans alike — after its 2017 and 2018 tax bills, when the company received federal refunds of $137 million and $129 million, respectively, due in part to a combination of tax credits and deductions.

In 2020, the company had an effective tax rate of 11.8%, reporting a provision for income taxes of $2.86 billion on income before taxes of $24.18 billion. Breaking it down by geography, Amazon reported a U.S. provision for income taxes of $1.68 billion on U.S. income before taxes of $20.22 billion, working out to a domestic tax rate of just 8.3%.

Amazon noted in its Form 10-K that U.S. companies are eligible for a deduction that lowers the effective tax rate on certain foreign income. Further, U.S. tax rules also provide for enhanced accelerated depreciation deductions by allowing the election of full expensing of qualified property, primarily equipment, through 2022. Amazon's federal tax provision included the election of partial expensing in 2020.

Lowest of the low

While the biggest firms often attract the most headlines for their tax rates and accounting maneuvers, these companies by no means have the lowest tax rates in the tech sector.

According to an S&P Global Market Intelligence analysis of select S&P 500 Information Technology companies, the IT company with the lowest effective tax rate in 2020 was Trimble Inc., a California-based hardware and software firm that provides positioning technology used for surveying, construction, agriculture, public safety and mapping purposes.

Trimble recorded an effective tax rate of just 1.1% in 2020, benefitting from a combination of research and development credits, intellectual property restructuring and tax law changes, and a large share of foreign-based earnings.

Chipmaker NVIDIA Corp. paid one of the lowest effective tax rates compared to its peers for 2020, at just 1.7%.

The company in a recent filing noted its effective tax rate for fiscal years 2021 and 2020 was lower than the U.S. federal statutory rate of 21% due primarily to income earned in low-tax jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands, Israel and Hong Kong, as well as the recognition of U.S. federal research tax credits and various tax benefits related to stock-based compensation.

Road to adoption

Of course, before any impact is felt, the new global minimum tax must be officially adopted, not only by U.S. lawmakers but by governments around the world.

Policy analysts said implementation of the global accord could face delays as governments wait and see how other countries respond, putting any first movers at a competitive disadvantage. They also noted the U.S. has already imposed its own version of a minimum tax with minimal success and to little fanfare from other countries.

The G-7 proposal still needs support from the Group of 20 economies, which is made up of 19 advanced and developing countries and the European Union, as well as buy-in from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the more than 100 countries that are part of a group known as the Inclusive Framework that has been negotiating the new tax rules.

Finance leaders from the G-20 are set to meet in Venice, Italy, in early July to discuss the new proposal.

"If there is agreement at the G20 ... in early July, there's a really long path from that agreement to actual implementable legislation. And then there's a long domestic path," Lilian Faulhaber, a tax law professor at Georgetown University Law Center, said in an interview.

Policy experts also noted that the G-7 proposal would only work if all major economies agreed to implement the minimum tax into law.

"If one [country] is going to do this, you need to do it all together so that nobody gains an unfair advantage," said Robert Atkinson, president of ITIF, an independent, nonpartisan research group based in Washington, D.C.