Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

23 Mar, 2022

By Kip Keen

| Exploration drilling at Hexagon Energy Resources' Halls Creek gold project in Western Australia. The mining sector may have to spend a lot more on exploration to meet growing metals demand, despite declining deposit quality and longer development cycles. |

The mining sector needs to spend far more on exploration to fill a thinning pipeline of assets in order to meet growing metals demand.

Global nonferrous exploration budgets reached $11.2 billion in 2021, barely more than half the peak of over $20 billion in 2012, helping drive a multiyear slump in major base and precious metals discoveries.

While the supply of key metals such as copper, zinc, nickel and gold is not about to fall off a cliff, the increasing cost and difficulty of finding deposits is stripping bare the stable of higher-quality assets that will be needed to replenish reserves years from now. To reverse course, major miners may have to start doing more heavy lifting, spending more and bulking up their exploration departments, some industry experts say.

"Ten years ago, we were saying that the 15- to 20-year timeline was looking bleak. Now we're saying, 'Oh boy, in five to 10 years, things can get rough,'" said S&P Global Commodity Insights analyst Kevin Murphy. "Investment needs to increase and it needs to increase beyond what we were spending during the last boom in exploration."

Discovery rates for gold and copper deposits have dropped precipitously over the past 10 years as the industry has produced fewer new resource announcements, according to Market Intelligence data.

"There were 52 initial resources recorded in 2020 — a five-year low and a far cry from the 10-year high of 175 new deposits in 2012, when grassroots exploration comprised around one-third of exploration budgets," Market Intelligence analysts said in their "World Exploration Trends 2021" report. "Additionally, there was an average of 65 initial resources annually from 2016 to 2020, nearly one-third less than the average of 91 from 2011 to 2015."

Murphy and other analysts noted there has been a risk-averse move away from grassroots exploration, where miners and explorers tackle new ground in search of deposits, to a greater focus on safer exploration near existing mines in recent years. This in part stems from the increasing difficulty and cost of finding deposits, which in turn has made it tougher for investors to fund risky early-stage exploration.

"When I started exploring in the late 1980s, if you had $10 million you could do a lot of damage with it in terms of going out and finding something. But now, that's just starter money," said John Burzynski, executive chair and CEO of Osisko Mining Inc., which ran one of the top exploration programs by spending in 2021.

To reverse the trend, major miners may need to start spending more on exploration instead of relying as heavily as they have been in recent decades on smaller exploration companies, which are typically funded by venture capital, to find deposits they can subsequently acquire, Burzynski said.

"I think you'll start seeing more senior mining companies developing their own exploration teams to go find the next 'big ones,' because they're the only companies that will have the ability to spend the type of capital needed to find new deposits," Burzynski said.

Major budgets

In recent years, majors have emerged as stronger players in the exploration sector, at least relatively speaking, but analysts do not see this as a sure sign of a new trend.

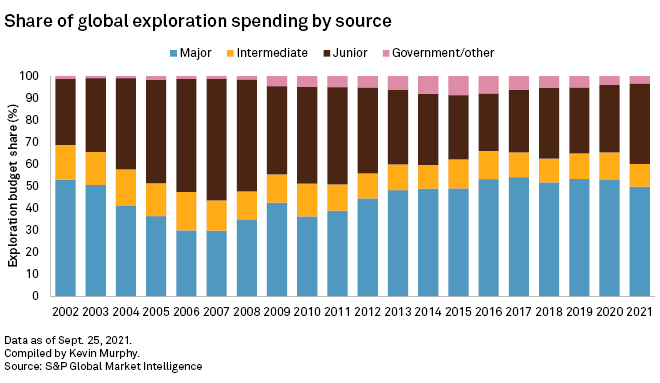

During the last exploration boom, which peaked in 2012, junior mining and exploration companies with revenues under $50 million per year often accounted for the majority of global exploration spending. After 2012, however, intermediate and major miners with revenues of $50 million-$500 million and over $500 million, respectively, grabbed a bigger share of the pie, accounting for the bulk of global exploration spending in recent years. But this was less a case of majors spending a lot more, and more to do with a shrinking of overall investment. Juniors faced tough financing markets, reducing their access to risk-willing exploration funds.

Some larger miners remain more focused on M&A to fill their immediate project pipelines than on spending a lot more on exploration. "The problem with M&A is that it doesn't actually help the industry at all," Murphy said. "It just swaps around the assets to different owners but doesn't add new ounces or new tonnes to resources in the ground."

With healthier financing markets in the past couple of years, junior exploration budgets surged 62% year over year to $4.1 billion in 2021, and their share of global exploration budgets jumped from 30.5% in 2020 to 36.5% in 2021. The extra spending has boosted new deposit discoveries, but nowhere near enough to reverse the discovery-rate decline.

"We need significantly larger budgets to really start finding those new quality deposits," Murphy said.

The issue of dwindling discoveries is not lost on major miners, though reversing this trend is not an easy matter. Deposit quality has declined, while the difficulty of developing new mines has increased, said Freeport-McMoRan Inc. Chair Richard Adkerson at the BMO Capital Markets Global Metals & Mining Conference Feb. 28.

"Grades are lower. Many of the resources are underground. Costs are rising. So developing new supplies [is] really challenging," said Adkerson, who could not be reached for comment. "And then you have the issue of community opposition to greenfield development. You have governments that can be complicated to deal with."

The pipeline of discovery to commercial production has also grown longer as permitting times have increased.

"It used to take seven years to find and get a mine into development," Anglo American PLC CEO Mark Cutifano, said on a Feb. 24 earnings call. "Now it takes 15 years on average and in many cases, 20 years ... And when you're in a commodity cycle ... then the reticence to allow development, or not get a first slice of the pie, actually constrains new developments." Cutifano also could not be reached for comment.

Majors roll up their sleeves

A few companies believe targeting early-stage exploration remains critical for growth. Barrick Gold Corp. President and CEO Mark Bristow, speaking on a Feb. 16 earnings call, cast exploration as a core part of Barrick's longer-term strategy.

"I've always believed ... you should get to a point where you can do both: Invest in your future and continue to make returns," said Bristow, who was not available to comment for this story.

Likewise, Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd. Executive Chair Sean Boyd noted on a Feb. 24 earnings call that discovering "gold in the ground" is crucial to creating value. "This is the toughest part of the business, finding pipelines of quality and profitability to grow," said Boyd. For its part, Agnico plans to spend aggressively on exploration in 2022 to grow mineral resources and reserves, Boyd said.

"You're starting to see majors start to partner up with juniors, who already have discoveries, and get involved at an earlier stage," said Stefan Ioannou, a mining analyst with Cormark Securities.

Ioannou is not sure, however, this means larger miners will start to multiply exploration budgets and lighten their reliance on M&A to fill pipelines.

"The majors obviously understand exploration is a tough game. That once you make a discovery, you still might be 10 years away from starting a mine, right?" Ioannou said.