Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

9 Jun, 2022

Lawmakers penning omnibus privacy legislation will need to work through some snags, but momentum on the bill — even after the November midterm elections — is unlikely to slow, experts say.

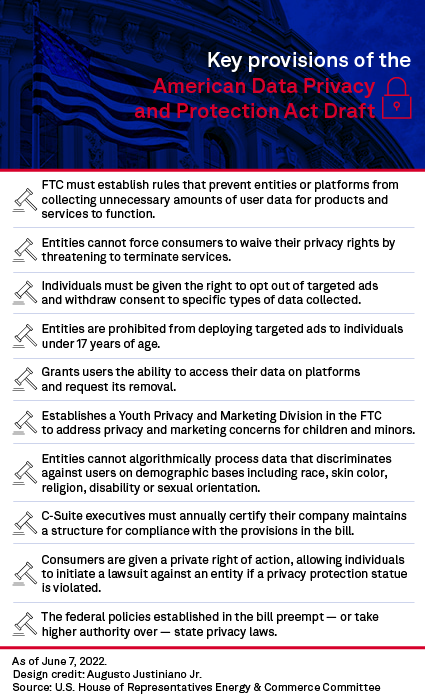

A draft of the American Privacy and Data Protection Act was unveiled June 3 by Reps. Frank Pallone, Jr., D-N.J., and Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Wash., as well as Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Miss. The draft is the first iteration of a comprehensive U.S. privacy bill that tech stakeholders have desired for years. It also marks the first bipartisan and bicameral law of its kind.

The bill, in essence, creates protections that block discriminatory use of Americans' data and requires platforms like Google LLC and Meta Platforms Inc. to minimize the amount of user data collected for their products and services to function. It also grants users the ability to opt out of targeted advertising and furthers data protections for children and minors. It also gives individuals a private right of action, where consumers can sue companies that have violated the law.

"I think it's the best shot we've seen in two decades toward adoption of a federal privacy law," said Caitlin Fennessy, vice president and chief knowledge officer of the International Association of Privacy Professionals.

|

Clashing on consumer rights

Among the points of contention in the bill are its private right of action provision and its federal preemption language.

The private right of action clause would enable consumers to file a lawsuit if they are harmed by a platform's failure to comply with the rules laid out in the bill. But these lawsuits can only begin four years after the law becomes official, giving companies a window for compliance.

Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., who chairs the Senate Commerce Committee, released a statement arguing that four years was too long. The senator has been circulating her own version of a privacy bill that takes this into account. Cantwell told reporters June 9 that she was unsure when a hearing would be held for her separate privacy bill.

It means that lawmakers would likely reduce the time window in order to compromise, said former Federal Trade Commission Chairman William Kovacic, now a law professor at The George Washington University.

"It seems like this is an open bidding contest and that number could come down," Kovacic said in an interview with S&P Global Market Intelligence. He added that the final number could be revisited even after the law passes.

Compliance and preemption

For the companies that must change their operations, four years is not a long time, said Cameron Kerry, former general counsel at the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Kerry, now a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, pointed to the significant time and resources that would be needed for entities to come into compliance with the pending privacy law.

The four-year period for invoking private right of action was decided in the wake of the 2018 California Consumer Privacy Act. Lawsuits against entities skyrocketed immediately after the state privacy framework became law and have continued to climb. The number of cases alleging violations of the CCPA increased by nearly 60% in 2021 when compared to 2020, according to law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP.

The preemption aspect of the bill is another area of contention for some consumer advocates. The draft privacy bill states that federal law would take precedence over state privacy laws, with some exceptions.

Omnibus privacy advocates argue that having laws in different states can create operational challenges for companies and individuals, but consumer protection advocates argue a weaker federal privacy law should not preempt more robust state laws. IAPP's Fennessy said that in order to bring the bill to life, a stronger preemption framework could be adopted to better match that of state laws.

When asked by Market Intelligence on June 9 if she would consider tapering down the four-year private right of action timeframe, Cantwell instead alluded to preemption concerns with state laws having stronger privacy provisions on the books.

"Let's just say there are many more [stronger laws] on my side than there are maybe on the other side," the senator said. "But I have to get my colleagues to support that concept."

Kerry stressed that, despite divisiveness, there is more agreement between lawmakers around basic consumer privacy protections than disagreement.

"There's an opportunity to put [agreed-upon aspects] into law," he said. Those areas include allowing consumers to opt-out of targeted ads, as well as allowing individuals to access their data and request its deletion.

Scarce resources

The FTC is responsible for the bulk of the enforcement matters relayed in the bill, but the legislation does not devote any tangible resources to the agency for carrying out the bill's demands.

The bill could do more in that area, Kerry said. Authorizations and financial appropriations will be needed to carry out the act, but they are not specified, he said.

The 3-2 Democratic-majority commission would certainly be willing to carry out the provisions in the bill, Kovacic said, especially under agency leader Lina Khan and newly confirmed commissioner Alvaro Bedoya.

As part of the enforcement tools given to the agency under the bill, the FTC should focus on creating rules that require entities to notify consumers when their data is being sold, said Shane Tews, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute focusing on privacy. It would serve as a way for 21st-century consumers to get control of their data, she added.

The FTC declined to comment on the legislation.

The consumer protection agency will also need to create rules for common carriers, namely ISPs or satellite operators that typically fall under the jurisdiction of the Federal Communications Commission. FCC Chairwoman Rosenworcel told Market Intelligence in a June 8 press call that the commission was assessing the legislation but did not provide further details.

What little time remains

Despite general bipartisan on key aspects of the bill, it could still take some time before the legislation becomes law. Congress is handling several national political matters including gun control, abortion rights and Russia's war in Ukraine.

Lawmakers are also working to pass sweeping tech legislation, with a floor vote expected in the coming weeks. After the chambers' August recess, many lawmakers will turn to campaigning in their states for midterm reelections, drawing more time away from bill revisions or potential for floor votes.

"There are a lot of planes circling the airport trying to land, and there aren't a lot of open slots," Kovacic said.

It will likely be a challenge to get the bill to Biden's desk before the midterms, though not impossible if full bipartisan agreement can be reached. Still, experts are confident the coalition moving forward on privacy legislation will remain intact into 2023.

A legislative hearing on the draft privacy bill will be held June 14 by the House Consumer Protection and Commerce subcommittee. No witnesses have been announced.