Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

31 Aug, 2021

By Zack Hale

| Sabino Creek flows through Sabino Canyon near Tucson, Ariz. Source: Moelyn Photos/Getty Creative via Getty Images |

A federal district court judge in Arizona vacated and remanded a Trump administration final rule that stripped Clean Water Act protections from roughly half of all wetlands and nearly a fifth of streams covered by a previous Obama-era rule.

The Aug. 30 ruling, which applies nationwide, effectively requires the U.S. to revert to a 2006 U.S. Supreme Court interpretation of the vague statute and implementing regulations promulgated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers until they develop a new definition of "waters of the United States." The district court's ruling is widely expected to be appealed.

Background

Former President Donald Trump campaigned on repealing and replacing the Obama-era regulation, the 2015 Clean Water Rule, which sought to clarify long-running uncertainty over how the agencies' decades-old interpretation of the Clean Water Act applies to waters such as wetlands and ephemeral streams.

While the Clean Water Act requires pollution permits for industrial facilities that impact "waters of the United States," the statute does not define what that phrase means.

In directing the EPA and Army Corps to review the 2015 regulation, former President Donald Trump instructed the agencies to apply a narrow jurisdictional test authored by the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia in the 2006 case Rapanos v. United States.

Scalia's test, which was only backed by three other justices, stated that federally protected waters must be permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water. Scalia also argued that only wetlands with a "continuous surface connection" to other federally protected waters should fall under the Clean Water Act.

Justice Anthony Kennedy disagreed, arguing in a concurrence that federally protected waters should include those that "significantly affect the chemical, physical, and biological integrity" of other federal protected waters. Kennedy also maintained that wetlands are covered by the Clean Water Act when they share a "significant nexus" with surface waters protected by the statute.

The high court's four justices backed Kennedy's test, and federal appeals courts have largely relied on Kennedy's test to decide Clean Water Act disputes.

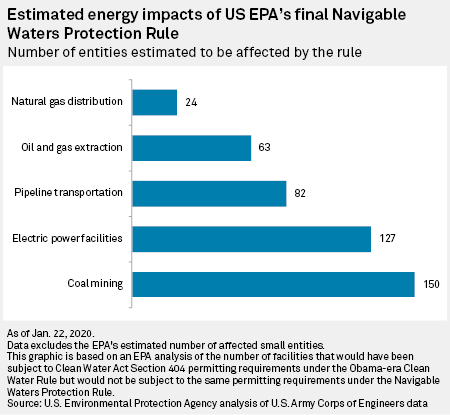

In September 2019, however, the Trump administration formally repealed the Obama-era Clean Water Rule, arguing that the Scalia test would give industrial developers and landowners such as farmers greater regulatory certainty. The Trump administration's April 2020 replacement regulation, dubbed the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, or NWPR, was projected to benefit hundreds of energy-related projects that would have otherwise needed Clean Water Act permits to dredge and fill streams or wetlands.

'Serious environmental harm'

Similar to the Clean Water Rule, the NWPR was immediately ensnared in dozens of district court-level challenges across the country.

In one suit, Pasqua Yaqui Tribe v. EPA (No. CV-20-00266-TUC-RM), a coalition of Arizona tribes told the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona that the NWPR was arbitrary and capricious because it disregarded the findings of a 2015 water study used to inform the Clean Water Rule.

Among its major findings, the 408-page study by EPA scientists concluded that "streams, individually or cumulatively, exert a strong influence on the integrity of downstream waters." It also found that wetlands often share connectivity with rivers and other surface waters even when no direct surface connection is apparent.

Siding with the tribes and rejecting the EPA's request to remand the NWPR without vacating it, Judge Rosemary Márquez cited the "seriousness" of the agencies' errors in enacting the NWPR, including ignoring the findings of the 2015 study. Citing case law, Márquez found that "an agency conclusion that is in direct conflict with the conclusion of its own experts ... is arbitrary and capricious."

The judge also noted that nearly every one of the 1,500 streams in New Mexico and Arizona assessed under the NWPR were no longer covered by the Clean Water Act and that the agencies identified 333 projects that would have required permitting under the Clean Water Act prior to the NWPR but no longer do.

"Remanding without vacatur would risk serious environmental harm," Márquez determined.

Finally, Márquez said the EPA and Army Corps will likely be altering the NWPR's definition of the "waters of the United States." They announced in July a two-step process to repeal and replace the NWPR, although that process is expected to take years to complete.

Márquez declined to address the plaintiffs' challenge to the Trump administration's 2019 repeal of the Clean Water Rule and set that matter for further briefing. Thus, for now, Kennedy's interpretation of the Clean Water Act will replace the NWPR.

Mark Ryan, a former EPA attorney who helped write the Clean Water Rule, said the Obama-era regulation could spring back into effect if Márquez should eventually find that the Trump administration acted improperly in repealing it. That would "change the amount of work [the agencies] have to do because if they don't have to write the repeal rule, they can focus all their resources on the replacement," Ryan said in an interview.

But Ryan also noted that hundreds of jurisdictional determinations issued under the NWPR's more-limited Clean Water Action will remain final. "Once the permit is issued and final, it's final," Ryan said.