Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

23 Nov, 2021

|

The Golden State building electrification movement continued to grow in the second half of 2021, with expanding participation from Southern California cities such as Encinitas. Source: Thomas De Wever/iStock/Getty Images Plus via Getty Images |

The movement to ban natural gas use in buildings reached a milestone in the second half of 2021, with California notching its 50th building electrification mandate.

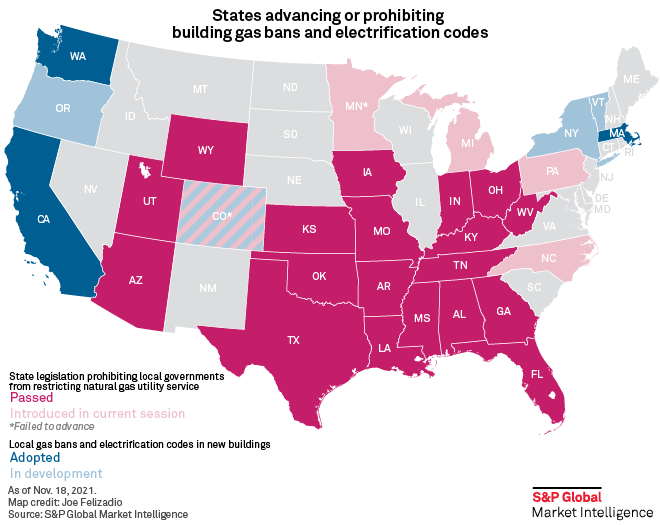

Meanwhile, the number of states prohibiting the policy appeared poised to top out around 20 this year, as all-electric construction ordinances advanced on the East and West coasts and cropped up in Oregon.

At the federal level, the Biden administration and Congress rolled out further support for building decarbonization and electrification. The U.S. Energy Department on Nov. 1 advanced its program to develop the market for cold weather heat pumps, an alternative to gas furnaces, by announcing six industrial partners.

The recently passed bipartisan infrastructure bill included funding for building energy audits and retrofits, a program to help states implement new building energy codes, and allocations for workforce training and higher education programs that support building decarbonization.

A larger package of more explicit building electrification policies remained tied up in congressional Democrats' Build Back Better Act. The version of the bill that passed the House of Representatives on Nov. 19 allocated $12.3 billion to the programs, down from initial funding of $18 billion.

Not too far from Washington, D.C., the city council in Richmond, Va., in September adopted a resolution that declared its commitment to phasing out gas use and called the continued operation of the municipal gas utility, Richmond Gas Works, an obstacle to achieving the city's climate goals. The motion reflected consideration of building electrification goals in locations including Miami-Dade County, Fla.; Ann Arbor, Mich.; and Las Cruces, N.M.

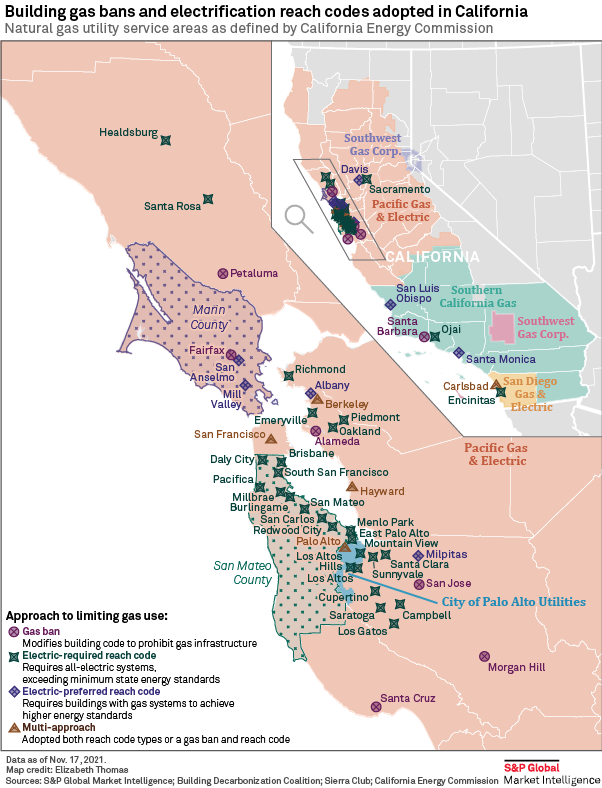

California hits 50

The Golden State movement gathered steam in Southern California, where Encinitas on Oct. 27 became the first city in San Diego County to adopt an energy reach code requiring all-electric construction of residential and commercial buildings. Neighboring Solana Beach is poised to follow after passing a similar reach code on Nov. 10.

On Oct. 27, San Diego Mayor Todd Gloria announced ambitious building decarbonization goals for California's second-most populous city. As part of its 2021 Climate Action Plan, San Diego said it is working toward prohibiting gas hookups in new buildings and announced it will seek to phase out 45% of natural gas use in buildings by 2030 and 90% by 2035.

Also in Southern California, Santa Barbara will prohibit gas hookups in new buildings beginning in 2022, after adopting an ordinance on July 27.

The Bay Area also piled on new ordinances. Fairfax adopted a building gas ban on Sept. 1, while Emeryville adopted an all-electric reach code for residential buildings on Sept. 13. Santa Clara capped the activity through mid-November with an all-electric reach code for both residential and commercial buildings, adopted on Nov. 16.

At the state level, California Public Utilities Commission staff issued a recommendation to eliminate subsidies for new gas hookups in order to encourage building decarbonization (19-01-011). The CPUC requested public comments and set a schedule for the proceeding, with a final decision expected by October 2022.

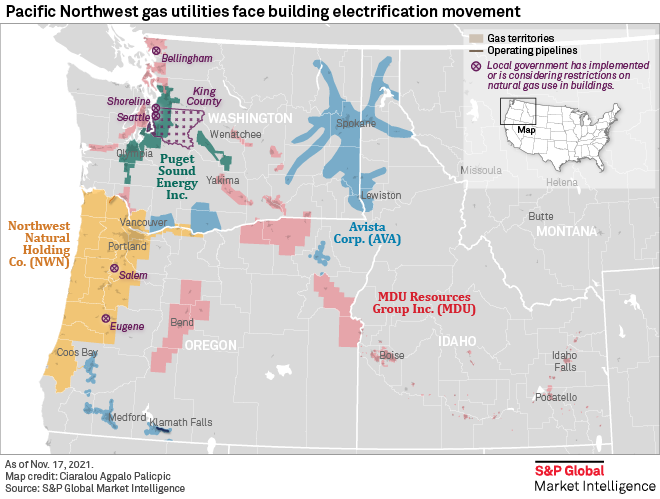

Pacific Northwest movement grows

The long-simmering building electrification movement in Oregon got a jolt with a pair of Nov. 17 resolutions in Eugene. The Eugene City Council directed the city manager to convene work sessions to begin considering an ordinance to require all-electric new building construction beginning in 2023. The council also asked city staff to develop a roadmap for decarbonizing existing buildings by 2045.

Shortly after the vote, the mayor of Milwaukie, Ore., signaled his city would follow suit. In October, Salem, Ore., also released its draft climate action plan, which included an overarching goal to increase energy efficiency and electrification of all buildings. The city is considering electric heat pump subsidies for existing buildings and an energy code that would require or incentivize all-electric construction.

In Washington, King County Executive Dow Constantine included restrictions on gas as part of a building code update announced in September geared toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The proposal would prohibit natural gas use for space heating and restrict its use in water heating in new commercial and multifamily residential buildings. The measure mirrors a building code update adopted in Seattle, the most populous city in King County.

The city council in Shoreline, Wash., on Aug. 16 directed its staff to draft an ordinance modeled after Seattle's electrification requirement.

Northeast efforts advance

A New York City bill to prohibit fossil fuel combustion in new buildings and renovations, introduced in May, got a hearing in the city council's Committee on Environmental Protection on Nov. 17.

On Oct. 29, a pair of Democratic New York state lawmakers reintroduced legislation that would prohibit any municipality from issuing a building permit for a new commercial or residential building that is not all-electric, beginning in 2024. Sponsors Sen. Brian Kavanagh and Assembly member Emily Gallagher would also require state agencies to report on rate designs, subsidies, policies and laws necessary to ensure the law does not negatively affect affordable housing construction and electric power affordability.

The law would allow exceptions where all-electric construction is not feasible, including where builders cannot meet code requirements without fossil fuel piping or where they require a natural gas or oil hookup for commercial cooking. The exception would be limited to the area of the building where the piping is necessary, and builders would have to provide wiring for conversion to electric appliances.

In Massachusetts, a growing coalition of more than 20 towns and cities continued to pursue various pathways to restrict gas use in buildings, as state agencies develop an opt-in highly efficient stretch energy code for new construction.

Following passage of a bylaw in Brookline, Mass., that strongly encourages all-electric building through a zoning amendment, other towns are pursuing zoning changes, according to Amar Shah, a manager for RMI's Carbon-Free Building program. However, several towns are waiting to see if the state attorney general allows the Brookline bylaw to stand, he said.

Several towns — including Acton, Arlington, Brookline, Concord and Newton — have submitted home rule petitions, which seek authority from the state legislature to restrict gas use in new buildings. A number of other towns, including Amherst, Belmont, Ipswich and Worcester, have passed resolutions declaring their support for electrification.

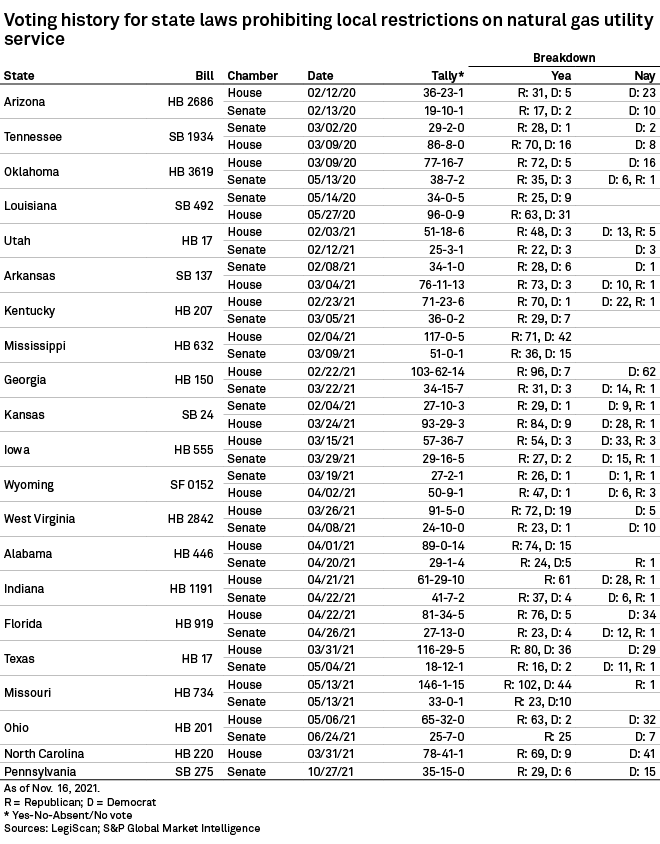

Preemption bills approach 20

The number of states with laws on the books that prohibit building gas bans appeared poised to surpass 20, as bills advanced in two state chambers.

The Pennsylvania Senate on Oct. 27 passed Senate Bill 275 with 35 votes in favor and 15 opposed. The bill would prohibit a municipality from adopting a policy that restricts or prohibits connection to a utility service or discriminates against a service provider based on the service provided. It also bars any policy to restrict a person or entity from accessing service provided by a capable, authorized utility.

The legislation advanced with a minor amendment to clarify that it would not stop a municipality from taking steps to reduce emissions from municipal facilities or operations.

A similar preemption bill in North Carolina that passed in the House of Representatives in March began working its way through the Senate in September. House Bill 220 advanced out of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Energy, and Environment to the Committee on Rules and Operations of the Senate on Oct. 5.

A final piece of legislation, House Bill 4575 in Michigan, has not gotten much traction since receiving a May hearing but remained up for consideration in the House of Representatives' Committee on Regulatory Reform.