S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

20 Jul, 2021

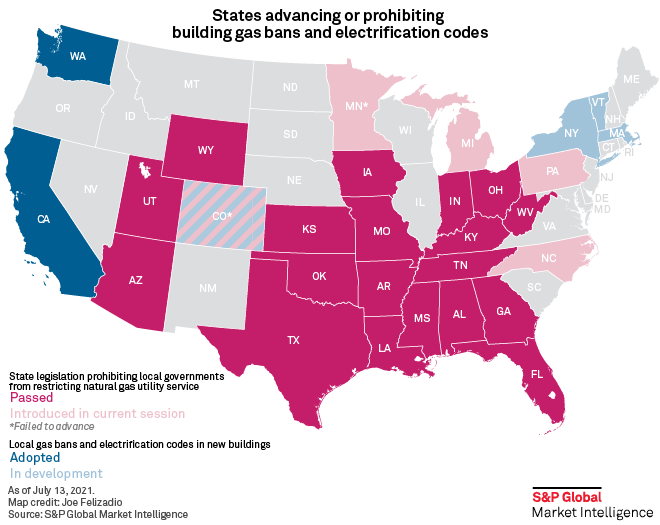

Local building electrification measures expanded and evolved in the first half of 2021, as the policy also percolated to the federal and international stage. Meanwhile, state laws prohibiting natural gas bans bolstered a growing firewall that now stretches across most of the southern U.S. and from the Rockies to the Midwest.

The Biden administration on May 17 announced a building decarbonization policy that seeks to accelerate electrification and support the market for heat pumps. The following day, the International Energy Agency recommended policymakers around the world ban fossil fuel furnace sales by 2025 and adopt building codes that would largely phase out natural gas use in buildings.

At the start of July, at least 19 U.S. states had adopted laws that prohibit the very policy that the IEA now endorses as a viable and efficient pathway to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Those states accounted for nearly one-third of U.S. residential and commercial gas consumption in 2019. Some of the biggest consumers — Ohio, Texas and Indiana — have passed such laws in recent months.

In New York City, city councilors introduced legislation to prohibit fossil fuel combustion in new buildings. Meanwhile, a housing panel delivered recommendations to New York's Climate Action Council to phase out gas use in new and existing buildings statewide and retire parts of the distribution system.

As state officials in Massachusetts develop an opt-in stretch energy code for construction — which "stretches" beyond minimum code requirements — some towns and cities are implementing interim measures to spur building electrification. Those include a new bylaw that uses zoning rules to restrict gas use in construction and renovations in Brookline, the first town to pass an East Coast gas ban.

In June, Colorado adopted a law that requires investor-owned electric utilities to offer incentives to build all-electric or transition from natural gas and fossil fuel heating and cooking. Notably, however, the law does not allow state regulators to ban new gas hookups or require residents to replace gas-fired furnaces. The state legislature had considered legislation to prohibit local building gas bans, but the bill died in committee.

Meanwhile, a Washington law that would phase out gas utility service across the state and a Vermont bill that would allow authorize Burlington to impose a carbon fee on new gas grid-connected buildings did not receive full chamber votes in state legislatures. In Oregon, the Eugene City Council signaled it would soon consider building electrification requirements.

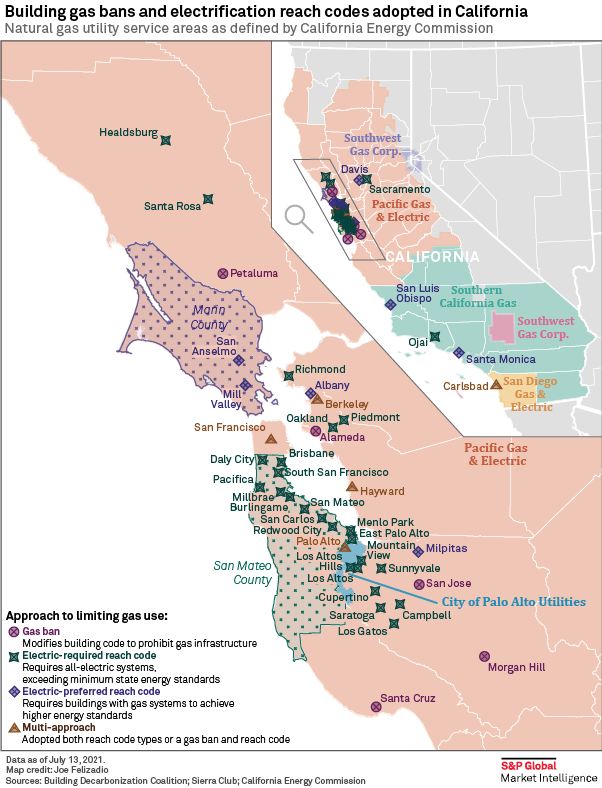

Sacramento headlines new California gas restrictions

Sacramento in June became the largest California city beyond the San Francisco Bay Area to require all-electric new construction. However, California's capital city will phase in the ordinance over several years, marking a more conservative approach than most local governments have taken to date.

The Sacramento City Council on June 1 adopted an electric-required reach code — which "reaches" beyond the state's mandatory codes — that will apply to low-rise buildings on Jan. 1, 2023, and to buildings with four stories or more on Jan 1, 2026. The ordinance cannot go into effect until the council adopts the 2022 statewide building code update and approves a process for obtaining a feasibility waiver, which is under development.

The ordinance includes a standard exemption for cases in which electrification is infeasible. Through 2025, it also exempts water heating systems in certain affordable housing and areas of industrial facilities with process load, or energy needed to run specific equipment. Sacramento also exempted cooking appliances in commercial kitchens, and agreed to review whether electric alternatives are available by July 2025. All exemptions require review and approval.

Some council members raised concerns about costs to businesses and residents following the COVID-19 pandemic and sought to delay adoption until city staff could conduct more analysis. A resolution to send the ordinance back to staff failed, and the council instead passed a resolution to adopt on a 7-2 vote.

The council on June 1 also resolved to establish a framework to electrify existing buildings, and by the end of 2022, city staff will develop a road map for decarbonizing Sacramento's building stock by 2045.

At least three other Bay Area cities adopted building electrification codes or gas bans in the second quarter, bringing the total to 45. Daly City and South San Francisco adopted all-electric reach codes on May 10 and June 9, respectively, while Petaluma adopted a building gas ban on May 17.

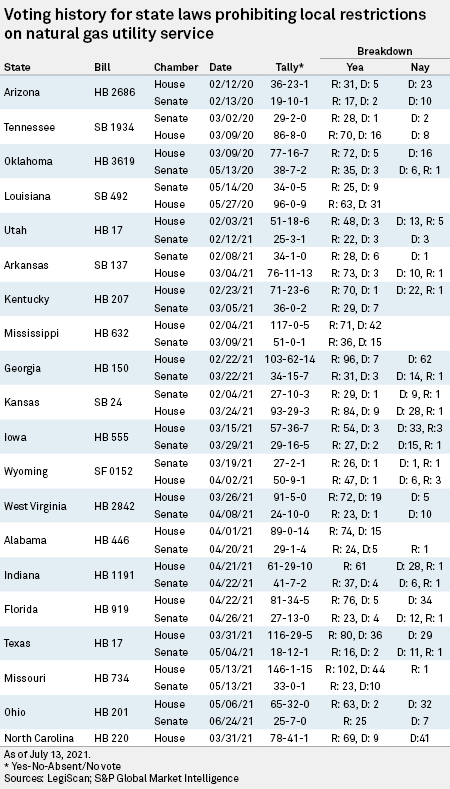

Large gas-consuming states adopt gas ban prohibitions

Missouri adopted the latest state prohibition on local gas bans after Gov. Mike Parson on July 6 signed into law a pair of wide-ranging utility bills that drew broad bipartisan support. Both bills — House Bill 734 and Senate Bill 44 — barred any Missouri subdivision from adopting an ordinance, resolution, regulation, code or policy that prohibits a utility connection or reconnection based on the type of service. House Bill 734 also directed state regulators to adopt rules allowing gas utilities to offer voluntary renewable natural gas programs and allowed electric utilities to securitize costs linked to transitioning to renewable generation.

Ohio became the second of the Northeast's big three shale gas-producing states to prohibit gas bans, after Gov. Mike DeWine on July 1 signed legislation advanced by Republicans on mostly party-line votes. House Bill 201 bars any township, county or municipal corporation from adopting an ordinance, resolution, building code or other requirement that limits or prohibits residential, commercial and industrial consumers from using natural gas distribution service or propane. House Bill 201 also enshrined in law the right to obtain gas service and propane.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis cleared his desk of the state's gas ban prohibition on June 21, nearly two months after House Bill 919 passed. The bill initially blocked restrictions on utility choice. However, the enrolled version barred local governments from restricting fuel sources distributed and used by electric and gas utilities, power generators, pipeline operators and propane dealers. Democrats mostly opposed the legislation, though several in both chambers joined Republicans in supporting it.

Texas House Bill 17 prohibits state and local regulators, planning departments and local governments from adopting any measure that would restrict utility service connection or reconnection based on the type of energy source. The law also prohibited restrictions on constructing, maintaining or installing any public or private utility service infrastructure. The legislation additionally blocks regulators and municipalities, along with utilities, from applying added charges to building permits that encourage builders to connect to a specific type of utility service, or that discourage developers from including facilities for the use of a utility service. Gov. Greg Abbott signed HB 17 into law on May 18. The bill drew bipartisan support in the House of Representatives but was mostly opposed by Senate Democrats.

Georgia House Bill 150 similarly barred any government entity — state, county or local — from adopting a policy that prohibits electric, gas or propane utility connections or reconnections, as well as propane sales. Gov. Brian Kemp signed the bill into law on May 6 after it passed with little support from Democrats.

The governors of Indiana and Alabama signed similar bills into law on April 29 and May 4, respectively.