S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

2 Jan, 2025

By Karin Rives and Jason Fargo

|

A floating wind turbine getting towed off the coast of Scotland. California plans to install similar technology but worries the incoming administration may rescind federal lease approvals. |

As they did under President-elect Donald Trump's first term, governors in blue states promise to use their legal resources and economic clout to protect climate goals and withstand deregulation efforts by the incoming administration.

"The states are unstoppable, and we remain unconstrained by anything the person in the White House can do," Washington Gov. Jay Inslee (D) said Nov. 15, 2024, during the COP29 climate summit. "We're going to keep this ball rolling."

The 24 governors of the US Climate Alliance, Climate Mayors' nearly 350 members, and the broader coalition of America Is All In have pledged to "relentlessly" continue their progress over the next four years. The US Climate Alliance and America Is All In formed in mid-2017 after Trump first announced he would pull the US out of the Paris Agreement on climate change. Climate Mayors formed in 2014.

But states are grappling with new challenges that may hamper their clean energy efforts over the next four years.

State fiscal trouble

At least 12 states that make long-term budget assessments face deficits or fiscal stress in 2025, and many more states report similar problems, according to a September 2024 analysis by the Pew Charitable Trusts. The state spending spree of pandemic-era surpluses ran out, forcing some legislatures to pare back climate-related budgets at a critical time.

California reduced water- and climate-related spending by 21% to $46.4 billion for the next eight years as part of a larger budget cut for 2025–26. Voters in the state responded Nov. 5, 2024, by approving a $10 billion climate bond to fund drought mitigation, offshore wind port infrastructure and other programs.

In the Maryland legislature, "everything is on the table," Senate President Bill Ferguson (D-Baltimore) said in a statement dated Nov. 15, 2024, after learning that the state faces a projected $2.7 billion deficit by 2026. Maryland's 2022 climate plan says the state must spend $1 billion annually to decarbonize the state by 2045.

The degree to which budget problems will interfere with states' climate progress will likely depend on how far along they are with their climate plans, predicted Colin Foard, a senior manager with Pew's Managing Fiscal Risks initiative.

"The more concrete and detailed they've gotten [with] those plans, the more likely they are to be able to defend that spending," Foard said in an interview. "States are at different stages."

| California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D), seen here at a September 2024 election event, has asked the state legislature for $25 million to cover the cost of litigation after Donald Trump takes office. |

Inflation and supply chain woes

The second most populous blue state, New York, is looking at a $13.9 billion budget gap between 2025 and 2029, according to the state's comptroller. The shortfall comes as the Empire State struggles to meet its 2030 climate goal.

New York's 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act requires the state to source 70% of its power from renewables by 2030 before decarbonizing its economy by 2050. As part of that plan, the state pledged to deploy 9 GW of offshore wind by 2035, only to run into delays.

In 2023, several offshore project developers canceled their deals with the state, citing cost increases that made the plans unworkable. New York then launched a new offshore wind solicitation, only to cancel those results in April after GE Vernova Inc. announced it would halt the turbine model the winning bidders had planned to use. A third bid process is now underway.

As they push forward with their energy plans while trying to get their fiscal business in order, blue states are preparing for a seismic federal policy shift on Jan. 20. Among their top priorities are defending state vehicle emissions policies and securing nascent offshore wind projects.

California vehicle waiver, tax credits on chopping block

Trump is widely expected to once again revoke a waiver the US Environmental Protection Agency has granted California for decades to set stricter greenhouse gas emission standards for cars and trucks than the federal government does and allowing other states to follow suit.

If Trump does revoke the waiver, a lawsuit challenging the waiver that 17 Republican-led states and business groups recently brought to the US Supreme Court is expected to end, and California and other blue states will likely sue the new administration for revoking the waiver.

Keeping the waiver intact is critical for California, said Noel Perry, founder of Next 10, a San Francisco think tank. The transportation sector accounts for 38% of the state's emissions and is a key reason the state is having difficulty meeting its 2030 climate target, even as California electric vehicle sales reached 25% of the total market in 2024, Perry said in an interview.

"California will fight tooth and nail if the Trump administration is going to again attempt to take that waiver away," Perry said.

Despite its long-standing climate efforts, California is not on track to meet its 2030 goal to cut greenhouse gas emissions 40% below 1990 levels, according to the latest edition of Next 10's California Green Innovation Index.

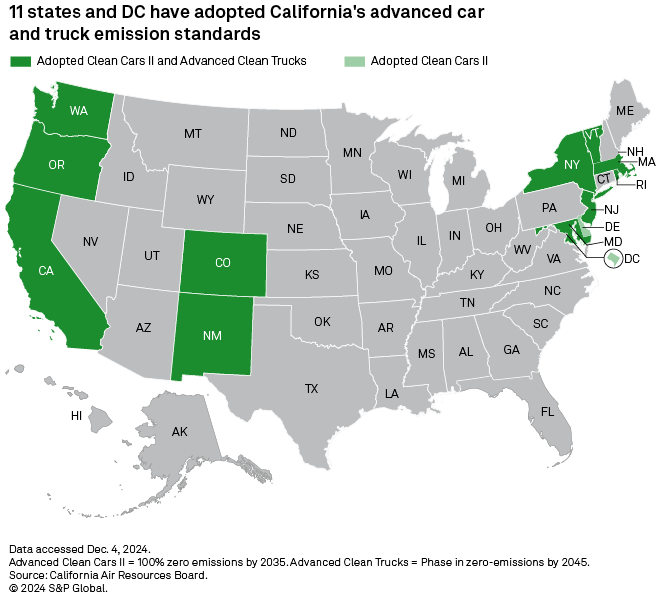

A lot is at stake also for the 11 states that have adopted the latest round of California's clean car standards, along with the District of Columbia. Transportation is the largest US source of greenhouse gas emissions.

Offshore wind battle looming

Amid uncertain EV policies, states like New York, California and Maryland with emerging offshore wind industries are also bracing for changes at the US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). The agency on Dec. 4, 2024, approved 2 GW of wind turbines off the coast of Ocean City, Maryland, the 10th offshore wind project under President Joe Biden that the Trump administration could reverse, consultants have said.

Meanwhile, California is seeking a final decision from BOEM for five floating offshore wind leases, the first to be built off the state's coast. The leases are part of California's plan to build 10.6 GW of offshore wind needed to meet its climate goals.

Perry said a major concern besides leases being delayed or revoked under Trump is what will happen to federal support for port infrastructure needed to support offshore wind. Long Beach and about a dozen other California ports must be built out to meet the state's goals, he said.

Trump is an outspoken opponent of wind turbines, and his election has introduced new uncertainty for developers as well. TotalEnergies SE Chairman and CEO Patrick Pouyanné told the Energy Intelligence Forum conference in London on Nov. 26, 2024, that he put the company's Attentive Energy One project in New York "on pause" after the election.

Legal fight ahead

If the second Trump administration will be better prepared and make fewer legal mistakes, state officials also plan to hit the ground running.

"We've been talking for months with attorneys general throughout the nation, preparing, planning, strategizing for the possibility of this day," California Attorney General Rob Bonta told a press conference two days after the November elections. "We've been through this before and we're ready to do it again."

California Gov. Gavin Newsom has requested $25 million to cover costs of the expected litigation. California Assembly member and budget chair Jesse Gabriel (D-Encino) introduced two bills on Dec. 2, 2024, to cover that funding request and another $500,000 for legal preparation, with the goal of having the bills signed into law before Trump's inauguration to a second term.

States have also come a long way on their climate journey since 2017, officials said. Inslee told the COP29 climate conference in Baku, Azerbaijan, just days after Washington voted to keep its carbon market program that 85% of the state's climate initiatives cannot be touched.

"He will not be able to stop our cap-and-invest [program], he will not be able to stop our low-carbon fuel standard, he will not be able to slow down our building codes," Inslee said of the incoming president. "He will not be able to stop any of these states from moving forward."