Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

16 Jun, 2021

This piece is produced by S&P Global Sustainable1, S&P Global's single source of essential sustainability intelligence to navigate the transition to a low carbon, sustainable and equitable future.

Key takeaways

➤ G7 carbon emission reduction targets unlikely to be met, S&P Global Platts data shows.

➤ No set financial targets for the global fight against climate change when trillions of dollars are needed.

➤ Financial pledges to developing countries represent a restatement of previous promises.

Hopes for significant new plans to tackle carbon emission reductions and soften the economic impact of climate change went largely unanswered at a meeting of G7 leaders in Cornwall, U.K., June 11-13. The Group of Seven meeting left many key decisions to the 26th U.N. Climate Change Conference, known as COP26, scheduled for November.

S&P Global Sustainable1 believes the lack of specific details from the G7 meeting creates doubt as to whether financing to halt global warming will rise to the necessary level.

At the meeting, the group of seven nations reiterated the need to rein in global warming to 1.5°C and committed to increasing 2030 emission reduction targets. The group — the U.K., the U.S., Canada, Japan, France, Germany and Italy — committed to reach net-zero emissions no later than 2050 and to halve its collective emissions in 2030 compared to 2010. G7 leaders also said they would submit aligned nationally determined contributions "as soon as possible" ahead of COP26 to help it achieve those gains.

Those goals will be difficult to attain. S&P Global Platts Analytics' Global Integrated Energy Model "most likely" outlook predicts G7 CO2 emissions will fall 24% between 2010 and 2030, less than half of what the G7 is promising.

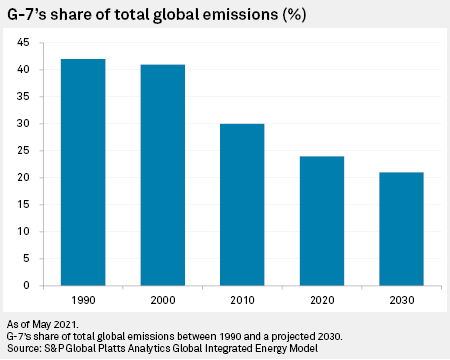

The G7's share of total global carbon emissions has, however, fallen. In 2020, the seven nations' share of total global carbon emissions was 24%, compared to 42% in 1990 and a projected 21% in 2030, according to S&P Global Platts Analytics data.

Companies have also been reducing their emissions and setting more ambitious targets. S&P Global Trucost data shows there was nearly an eightfold increase in the total emissions covered by a reduction target between 2015 and 2019. However, that figure only represents 18% of the total 2019 emissions made by the 1,200 largest global companies. In other words, we will need still more ambitious targets.

The struggle to close massive funding gap

At its weekend meeting, the G7 also backed renewable energy and a move away from coal, while acknowledging the mammoth task of financing the economic transition.

"To close the gap between the funds needed and actual finance flows requires mobilizing and aligning finance and investment at scale towards the technologies, infrastructure, ecosystems, businesses, jobs and economies that will underpin a net-zero emissions resilient future that leaves no one behind," the seven nations said in a joint communiqué at the end of the meeting.

"This includes the deployment and alignment of all sources of finance: public and private, national and multilateral."

But the group stopped short of putting an actual number on how much that might cost and, importantly, how to get there.

Fighting climate change requires a vast amount of money. Limiting warming to 2°C by 2050 will require $3 trillion annually in investment, according to an estimate by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Getting to 1.5°C would require $3.5 trillion annually, the IPCC predicts.

Of that amount, about $2.4 trillion — or about 2.5% of global GDP — will be needed annually over the next 15 years for clean energy-related investments, the IPCC said. In comparison, global total investments in clean energy and energy efficiency in 2019 reached only $635.8 billion, according to the International Energy Agency.

The market for sustainable finance has been growing. The green bond market — financing for debt that is linked to environmentally friendly projects such as solar power or wind farms — expanded from virtually nothing in 2012 to $282.05 billion in 2020, based on figures from the nonprofit Climate Bonds Initiative, which promotes green investment.

Transition finance, a bridge between traditional and sustainable financing for the largest carbon emitters such as oil and gas as well as shipping, could contribute $1 trillion annually, according to S&P Global Ratings.

Pledge for developing nations falls short of needs

One specific goal that the G-7 agreed on was the desperate need for climate financing for the developing world. The G-7 countries reaffirmed their goal to invest public and private sector funds to the tune of $100 billion for developing countries by 2025 — a target set initially for 2020 at the U.N. Climate Change Conference in 2009.

That amount is a drop in the ocean compared to what is needed. The World Bank's International Finance Corp. has estimated funding needs of $29.4 trillion by 2030 in infrastructure, energy-efficient buildings, renewable energy and water management in emerging markets.

At the same time, G-7 leaders committed to increase spending in developing countries but provided little detail on how they expect to get there. Only two G-7 members committed at the meeting to increase their financing targets: Canada said it would double its climate finance to C$5.3 billion over five years from C$2.65 billion in 2015, while Germany plans to increase its funding to €6 billion by 2025 from €4 billion in 2020.

The $100 billion goal has been around for some time. In 2009, developed countries at COP15 agreed to mobilize that amount for developing nations to finance climate change, and the jury is still out on whether that promise has been kept. A report by independent experts in December 2020 suggested the target would not be met because of a lack of easy access to funds as well as low financing for the poorest countries. The coronavirus has stymied the growth of climate financing to developing countries.

Much of the money for emerging markets is likely to be earmarked for moving from coal into renewable energy, and the G-7 highlighted joint programs by multilateral development banks like the World Bank to commit up to $2 billion in the coming year to accelerate the transition. Those funds should mobilize up to $10 billion with input from the private sector in renewable energy projects in developing economies, the G-7 said.

The G-7 singled out coal, particularly in developing markets, warning that "unabated coal power generation is incompatible with keeping 1.5°C within reach."

The G-7 also echoed recent findings by the International Energy Agency that international investments in coal need to stop, and the seven nations committed to an end of "new direct government support for unabated international thermal coal power generation by the end of 2021."