Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

WHITEPAPER — Jun 18, 2024

By Byron McKinney and Jeremy Domballe

Nearly two years since the Oil Price Cap Coalition introduced restrictions on the price of Russian crude oil and refined products, a significant number of enforcement actions have taken place to pressure shippers, commodity traders, financial institutions and charterers to work within specified parameters when transporting Russian oil. Individual vessels, owners and charterers have been added to the US Department of Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list and to the UK HM Treasury's Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI) sanctions list for shipping oil outside the price cap. In this context, the increasing scrutiny placed on the maritime industry highlights the need for continued vigilance to ensure the vessels and owners working to transport Russian oil or operating within a "shadow" fleet are identified and understood with regard to their activity and particulars.

A shadow fleet of vessels emerged as a result of Russia stating its intention not to work or cooperate with the price cap. This action led to several established vessel operators exiting the Russian oil trade. Therefore, new shippers had to be found to continue transporting pre-2022 Russian oil production output. New shipping companies were setup in locations such as India, the United Arab Emirates and Hong Kong, where new partners and buyers of Russian oil were found and new insurance firms were created to offer protection and indemnity to the shadow fleet.

The shadow fleet, therefore, remains an important topic for consideration, especially for those undertaking vessel compliance. Not knowing the ultimate or group owner of a vessel or fleet of vessels poses a degree of risk. The ability to determine the origin of oil is also a requirement placed on firms engaged in the oil trade to not unwittingly transport Russian oil or be in contravention of regulation in the EU, for example, failing to adhere to the restrictions on Russian oil entering an EU port either directly or via a ship-to-ship (STS) operation. The need to identify the shadow fleet and be aware of its actions are hugely important when a Russian nexus to a vessel or firm is no longer obvious.

S&P Global Market Intelligence originally documented a shadow fleet estimate in March 2023 and since then, others have also contributed to this task. Numbers range in terms of how many vessels are in the actual shadow fleet and differences in methodology also occur as to what constitutes a shadow fleet ship. To try to overcome the dangers of a single number attributed to the size of the shadow fleet, it has been deemed worthwhile in the context of this paper to break down ships engaged with Russian oil trade into different tiers. These tiers have been assigned risk in proportion to their circumstance and the activity of the vessels within it, and have been formulated by Market Intelligence and S&P Global Commodity Insights for the purpose of this paper. For example, Tier 1 is highest risk and contains sanctioned vessels already identified by enforcement agencies to be shipping Russian oil outside the price cap limit. Attributing ships to a tier-based risk value will then allow for a determination of what percentage of the global tanker fleet are currently engaged in the trade of Russian oil.

The takeaways below are as of the date of publication of this whitepaper and are based on information available to Market Intelligence.

Research by Market Intelligence and Commodity Insights estimated that 1,431 individual ships have been involved in the transportation of Russian oil since Dec. 5, 2022. This number constitutes 24% of the global in-service oil and products tanker fleet, with a deadweight tonnage equal or greater than 27,000.

Additionally, a shadow fleet, made up of tankers in Tier 1 and Tier 2 accounted for an estimated 591 unique ships, or 10% of the global in-service oil and products tanker fleet, up 33% since previous estimates were calculated by Market Intelligence in March 2023. The significant rise in this number can be explained by the introduction of new sanctions measures and designations by the US Department of the Treasury in fourth quarter 2023 and first quarter 2024, the sale of tankers by Greek owners to Russian entities, and new owners establishing themselves within the Russian shadow fleet, often based in India and the UAE.

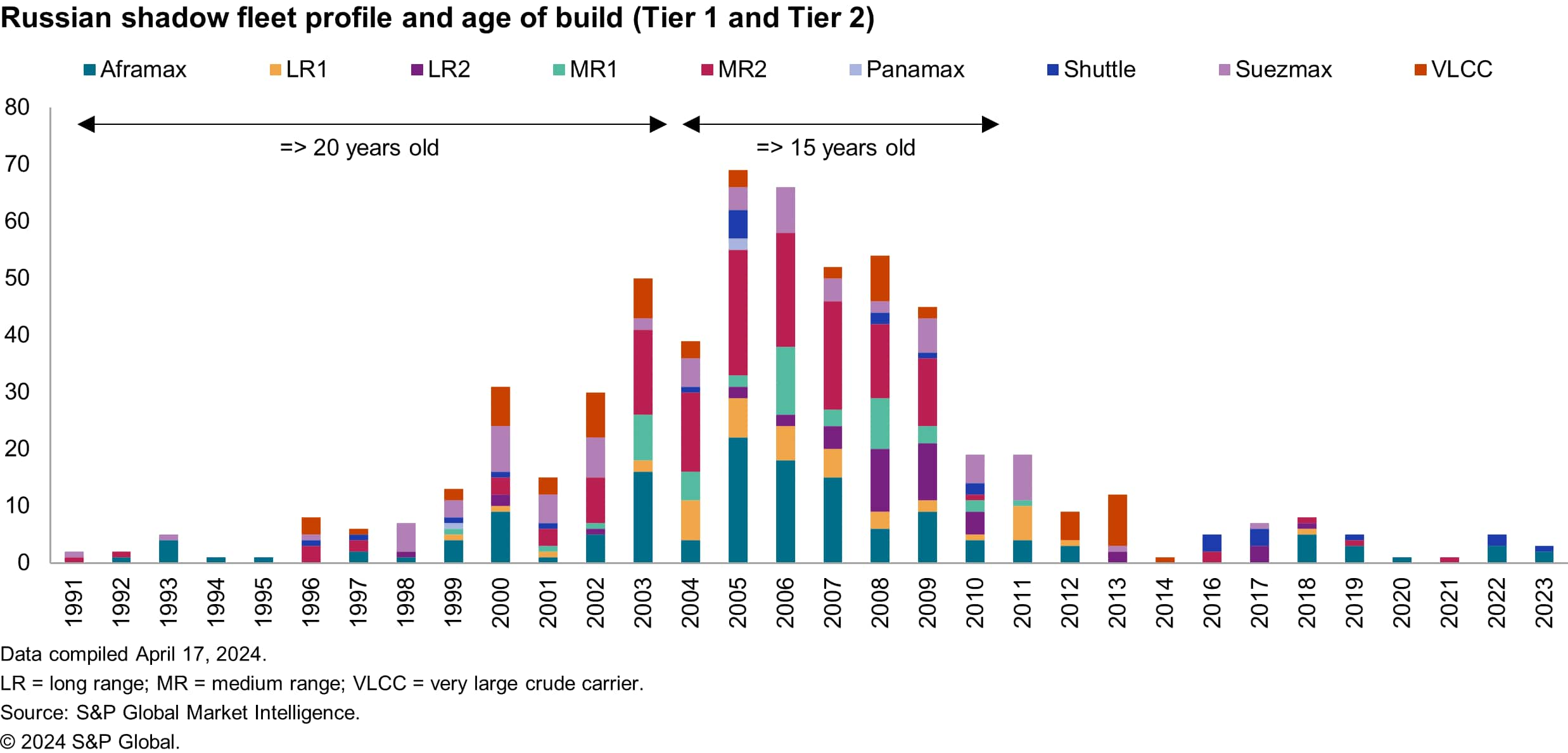

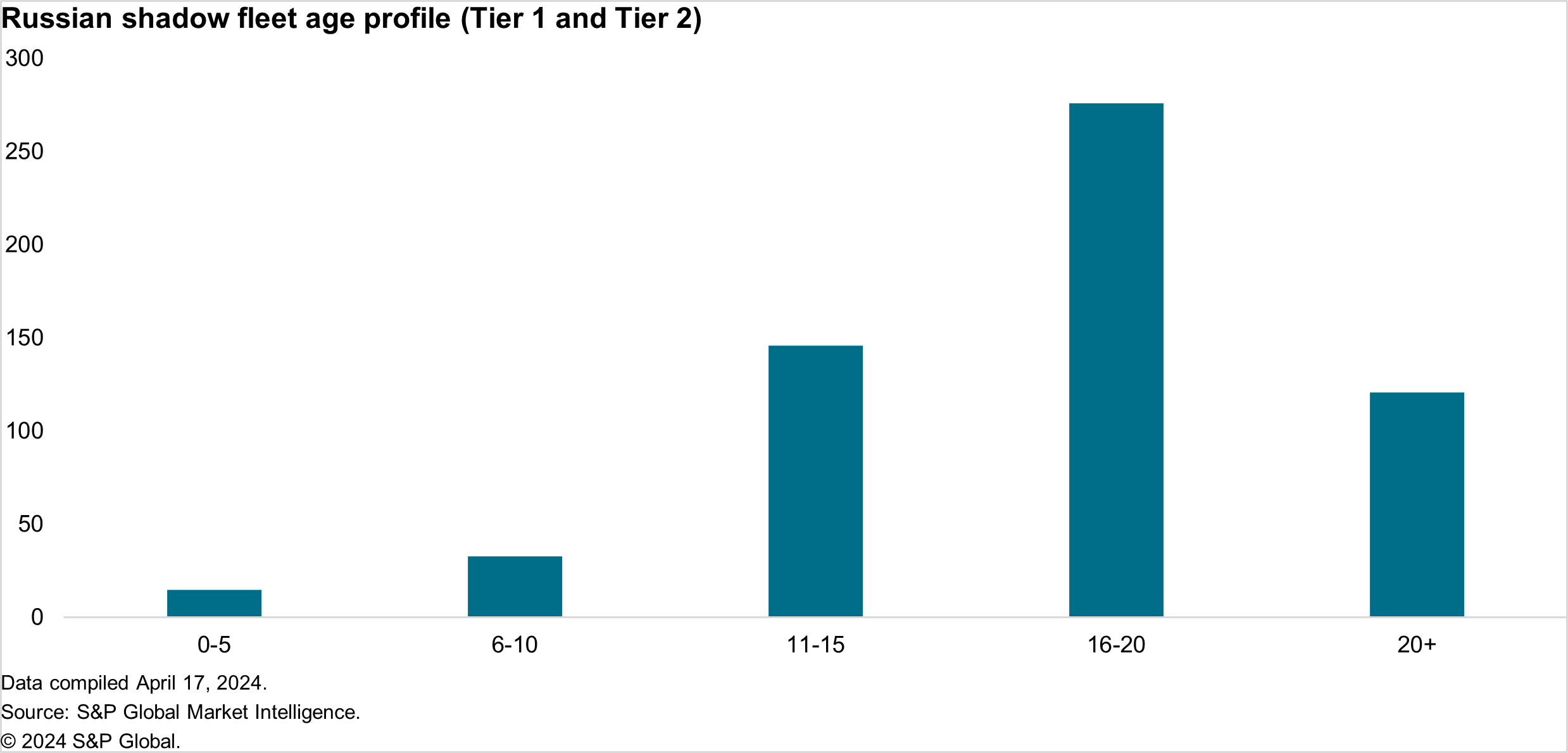

One of the key attributes to the shadow fleet has been the age of a vessel. It has been frequently noted that the shadow fleet is comprised of mainly older tankers, with the analysis highlighting a large number of ships older than 15 years.

The profile by age identifies approximately 397 vessels in the shadow fleet that are older than 16 years, with the largest concentration in the 16-20-year age bracket.

Medium range (MR) 2 tankers (50,000 dwt) make up the largest class of vessels within the shadow fleet, with Aframax vessels (100,000 dwt) also contributing significantly. For these two vessel classes, an estimated 165 ships in the shadow fleet are aged between 17 and 21 years old.

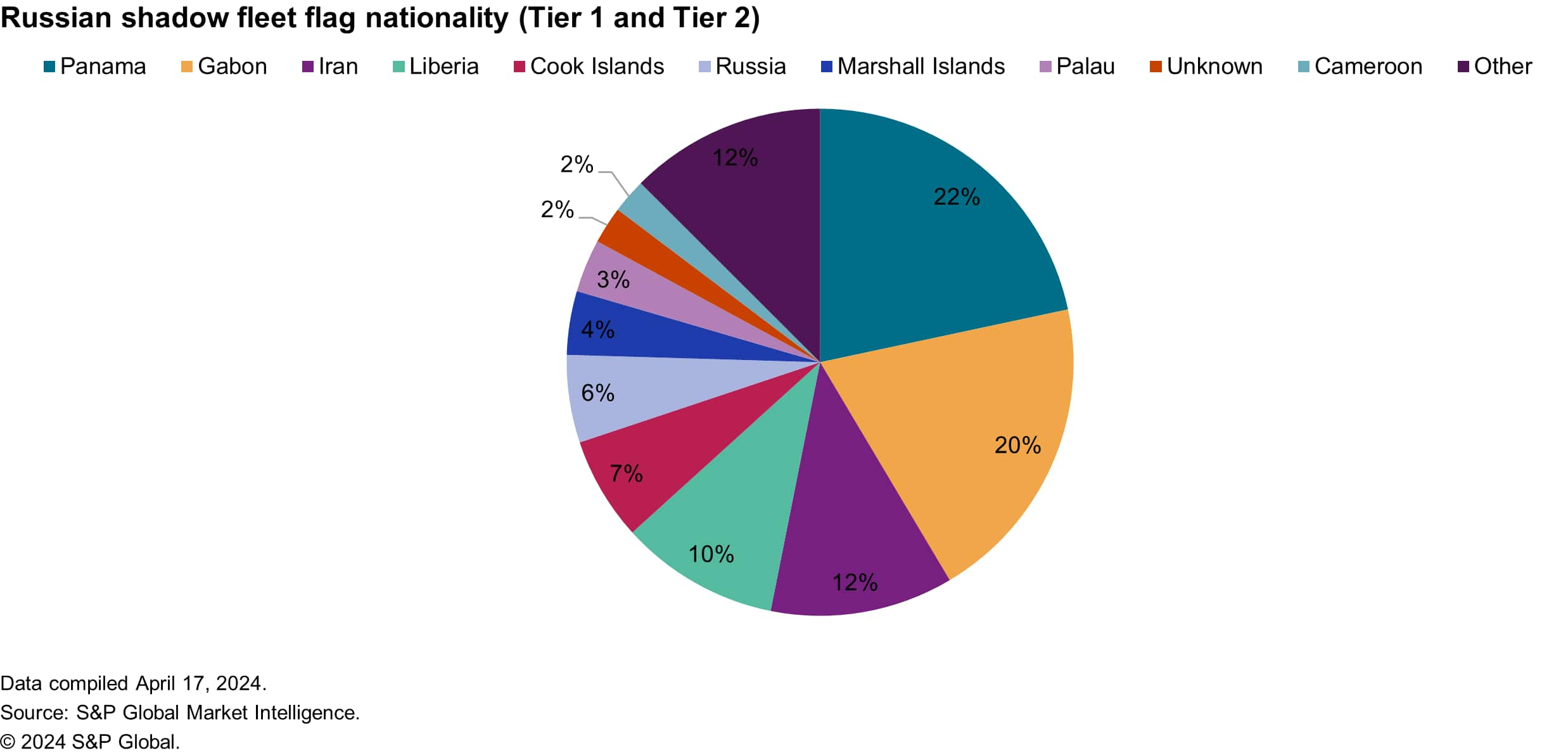

Flag nationality has often been a moving target in its relationship to the shadow fleet, with many of these vessels frequently flag hopping. Panama and Gabon currently account for 42% of the shadow fleet's nationality, with Gabon being a major location for the registration of ships in this fleet and increasing its share over the last 12 months. At least 36% of Gabon's currently registered vessels have definitive links via group owners to Russia. About 47% of vessels registered with Gabon have missing group owner details, compounding its reputation as a "light touch" regulatory flag.

Other flags in the shadow fleet are more well known, belonging to countries such as Iran, Russia and Cameroon.

Click here to download the full complimentary paper where we will cover:

Maritime-related sanctions

Deceptive shipping practices

Tier 1, 2 and 3 analysis − Typology, ownership, operator, flag register, age, port state control, classification societies, P&I club, case study and more

Subscribe to our complimentary Global Risk & Maritime quarterly newsletter for the latest insight and opinion on trends shaping the compliance and shipping industry from trusted experts.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

How can our products help you?