Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jul 22, 2020

What can we learn from the Swedish approach to COVID-19?

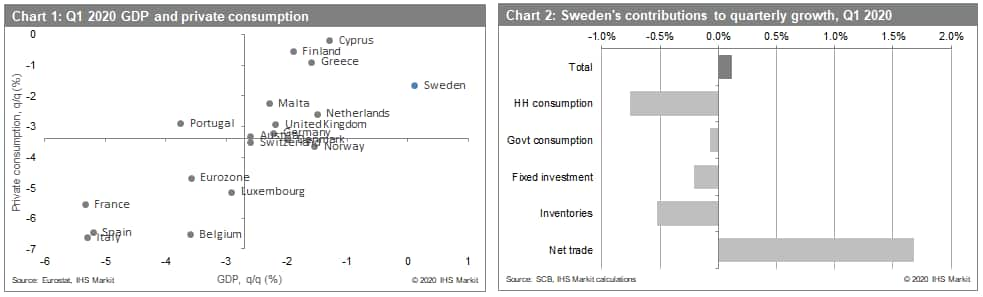

- Sweden's outperformance in Q1 was largely unrelated to its COVID-19 strategy, as all domestic demand components were a drag on headline growth, offset by a large positive contribution from net trade.

- Key downside risks include a collapse in goods exports without a corresponding drop in imports and an elevated unemployment rate causing negative spillovers into the banking sector and the broader economy.

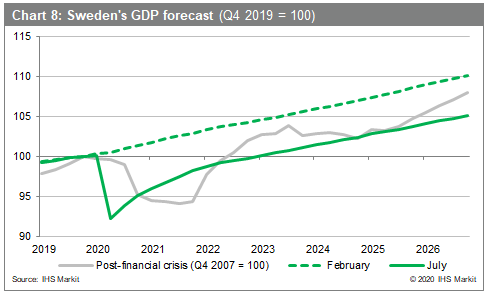

- The Swedish economy is likely to outperform its peers in 2020, but not over the medium-term. We expect Swedish GDP to return to its end-2019 level at the end of 2022.

Impact on the economy

The Swedish economy was the only one in Western Europe that did not contract in the first quarter, apart from Ireland where GDP was distorted by tax-related transactions of multinationals. However, Sweden's underlying growth drivers do not necessarily vindicate the government's strategy. Although the country's private consumption fell by less than the Western European average, the decline was larger than in Finland, which imposed a strict lockdown. Despite the strict lockdowns across Europe denting foreign demand, net exports were the only positive contribution to Swedish growth, driven by the largest quarterly surge in goods exports in a decade. Without the contribution of net exports, the Swedish economy would have contracted by 1.6% in the first quarter, which would have been slightly less severe than in Denmark and Finland, but more severe than in the Netherlands and Norway. Given the importance of the first quarter for full-year growth, we currently expect Sweden to outperform the eurozone and its Nordic peers in 2020. However, there are some key near-term risks.

Short-term risks

According to leading indicators, goods exports, the key growth driver in the first quarter, are heading for a major contraction. They were down by 26% year on year (y/y) in May, equivalent to the nadir reached during the financial crisis, while manufacturing export orders sank in June to a lower level than in 2008-09. This is likely to have an effect on investments and employment in the most affected sectors.

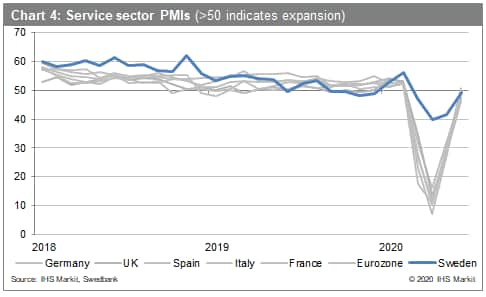

Private consumption is likely to hold up better than elsewhere in Europe in the second quarter, but this will hurt net exports. Sweden's service-sector purchasing managers' index (PMI) has not sunk to the low teens, unlike elsewhere in Europe. This is likely to have a mixed impact on second-quarter growth as stronger private consumption is likely to have pushed up imports, removing the key support provided by net exports.

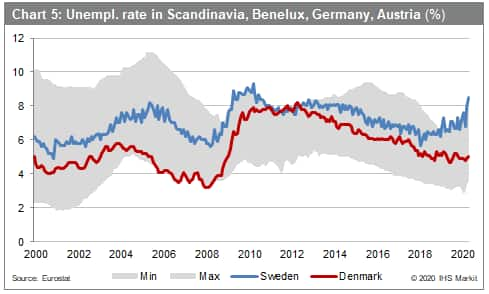

Despite the lack of a strict lockdown and large fiscal and monetary policy stimulus, Sweden's unemployment rate shot up the most among its peers and is likely to peak in double digits by early 2021. This is a key tail risk for the banking sector and the wider economy, given that Swedish households are among the most indebted in Europe, with a debt-to-disposable-income ratio of above 180% at the end of 2019.

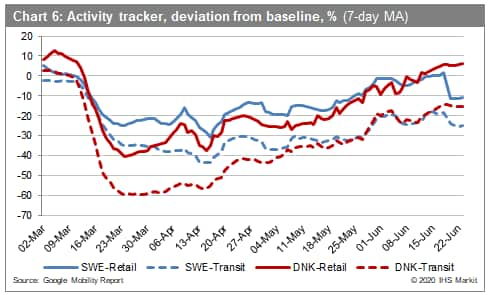

According to real-time activity trackers, Sweden is losing its advantage over economies that imposed a strict lockdown and successfully contained the virus. While the latter are likely to experience a strong rebound in consumer spending owing to pent-up demand, near-term activity in Sweden may remain relatively subdued as a result of consumers' concerns about the still-wide circulation of the virus.

Outlook

The Swedish economy outperformed all of its peers in the first quarter, although the success was unrelated to its COVID-19 virus strategy but rather driven by strong foreign demand for its goods exports. According to leading indicators, this key support will diminish in the second quarter, while consumption-related imports are likely to make net trade a drag. The technical rebound from the third quarter of 2020 also risks being subdued, owing to the persistence of restrictions, a rise in the unemployment rate, and fears about the high prevalence of the virus.

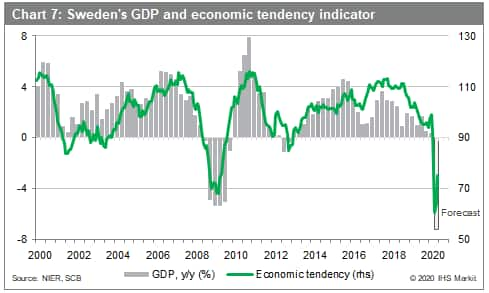

In our July baseline, we expect a large GDP drop of around 8% quarter on quarter (q/q) for Sweden in the second quarter, consistent with the leading survey data, which have a historically strong correlation with GDP even in downturns. The rebound in the third quarter is likely to be more subdued in Sweden than elsewhere in Europe, as in the latter it will be related to the unwinding of lockdown measures and extremely high growth rates in some sectors that have seen a near-total collapse in activity. This will not be the case in Sweden, where levels of domestic activity never collapsed to the same extent and where a relatively high infection rate in the summer months may weigh down on consumer spending.

For the full year 2020, IHS Markit expects the economy to contract by just under 5%, which is roughly half the rate of contraction forecast for the eurozone. Sweden is likely to return to the end-2019 GDP level at the end of 2022, more than a year earlier than the eurozone, but similar to Denmark. The crisis is likely to leave permanent output losses, with the Swedish economy expected to be permanently lower by around 5% compared with our February baseline.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhat-can-we-learn-from-the-swedish-approach-to-covid19.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhat-can-we-learn-from-the-swedish-approach-to-covid19.html&text=What+can+we+learn+from+the+Swedish+approach+to+COVID-19%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhat-can-we-learn-from-the-swedish-approach-to-covid19.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=What can we learn from the Swedish approach to COVID-19? | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhat-can-we-learn-from-the-swedish-approach-to-covid19.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=What+can+we+learn+from+the+Swedish+approach+to+COVID-19%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhat-can-we-learn-from-the-swedish-approach-to-covid19.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}