Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jul 25, 2018

Wage pressures remain weak across Western Europe

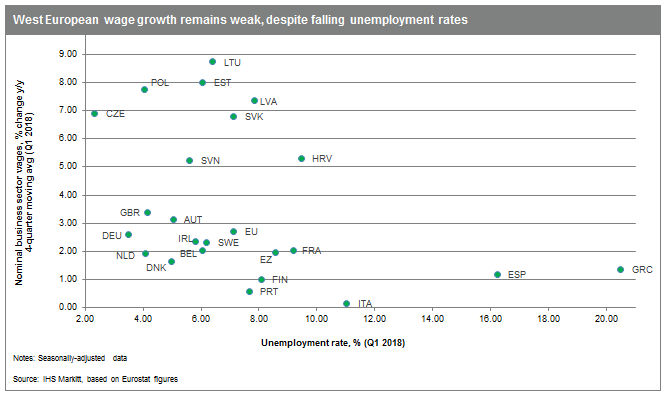

- Salary hikes have remained weak across Western Europe, even in countries with low unemployment rates.

- A variety of factors have dampened wage growth, including falling employment rates, outsourcing, the weakening power of labor unions in the wage bargaining process, the retirement of baby boomers, and slow productivity growth.

- Productivity-boosting reforms could raise wage growth over the medium term, but downside risks remain elevated.

Explaining lackluster wage growth

In recent years, wage growth has remained stubbornly weak throughout Western Europe, even where unemployment rates are low. There are a number of possible explanations for that phenomenon:

- A slow recovery from the 2008-09 global financial crisis and subsequent Eurozone debt drama in many countries, keeping employment rates depressed. As lower-wage workers who lost their jobs during the crisis reenter the labor force, overall salary growth is diminished.

- Weak productivity gains (with Ireland and Malta being the main exceptions).

- Outsourcing to lower-wage countries in Emerging Europe or Asia. Outsourcing is especially prevalent in the services sector, which is often more price sensitive than manufacturing and where the cost of shifting operations abroad is typically much lower. • The diminished power of labor unions in the wage bargaining process, especially given the weak inflation rates of recent years. In the Eurozone, consumer price inflation averaged just 0.7% annually in 2013-17.

- A phenomenon known in France as the "Noria" effect. As large numbers of baby boomers leave the workforce and retire, they are being replaced with younger workers with less experience, and therefore lower salaries. Thus, we are seeing a shift in the age pyramid, with fewer highly-paid people at the top and a replacement by lower-salaried young people at the bottom.

- Skills mismatches keep unemployment rates high, as the number of people with technical degrees declines. Education reforms and retraining programs may be needed to ensure that the workforce meets the demands of local companies.

Is the Phillips curve still valid in Western Europe?

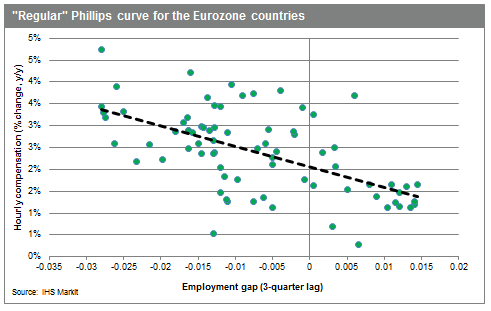

In economic theory, the Phillips curve shows an inverse relationship between the unemployment rate and wage growth: salaries are expected to increase slowly when the unemployment rate is high and quickly when the jobless rate is low. In the longer term, there is believed to be a specific level of unemployment which does not cause inflation to accelerate, known as the non-accelerating wage rate of unemployment (NAWRU). If the jobless rate rises above this neutral level, inflation will slow and potentially turn to negative territory. If unemployment is too low, inflation would accelerate.

In practice, the NAWRU is difficult to define, and few economists believe that the "natural" rate of unemployment remains stable in a given economy. Looking at Eurozone data from the last 20 years, the relationship between hourly wage growth and the employment gap (measured as the difference between the unemployment rate and the NAWRU) does not show a clear pattern.

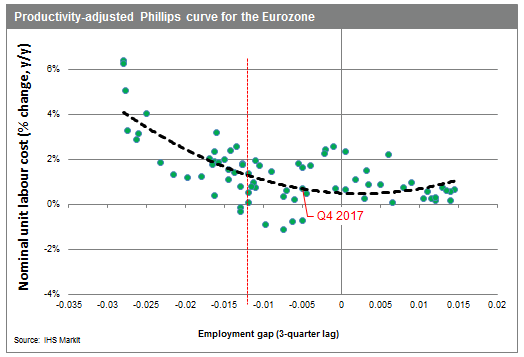

Nevertheless, when we adjust for productivity, the pattern is

much clearer, indicating that the employment gap must fall below a

certain level before wage pressures rise more rapidly.

As demonstrated by the chart below, the slope of the curve becomes

steeper when the Eurozone's jobless rate falls more than one

percentage point below NAWRU, a point beyond which wages rise

significantly faster than productivity. Clearly, the region is

close to that inflection point today (in late 2017, the

unemployment rate was half a percentage point below the neutral

rate), but the recovery still has some traction to gain before one

can expect sustained wage pressures.

Outlook

While some analysts believe that an acceleration of wage growth is just around the corner, others see limited prospects for a stronger recovery. Germany is among the most obvious candidates in Western Europe for stronger salaries. Indeed, the wage moderation that has characterized the country since the reforms of the 2000s appears to be ending, as heightening labor shortages give trade unions increased bargaining power. In early 2018, new, higher salary agreements were reached in a number of key sectors. Outside of Germany, however, most Western European countries may see a slower acceleration of wage growth, especially where unemployment remains elevated.

While IHS Markit expects that most EU countries will see at least moderate growth in nominal wages over the medium term, downside risks exist. Looking ahead, efforts to improve the business environment and raise productivity will be especially important in boosting wage growth. Although many companies were reluctant to invest amid the crises of recent years, productivity could be raised through investments in machinery, human capital, and public infrastructure. Nevertheless, some observers fear that wage growth could be permanently diminished as technological development and outsourcing threats reduce workers' bargaining power and boost investment in capital.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwage-pressures-72518.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwage-pressures-72518.html&text=Wage+pressures+remain+weak+across+Western+Europe+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwage-pressures-72518.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Wage pressures remain weak across Western Europe | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwage-pressures-72518.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Wage+pressures+remain+weak+across+Western+Europe+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwage-pressures-72518.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}