Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Aug 29, 2017

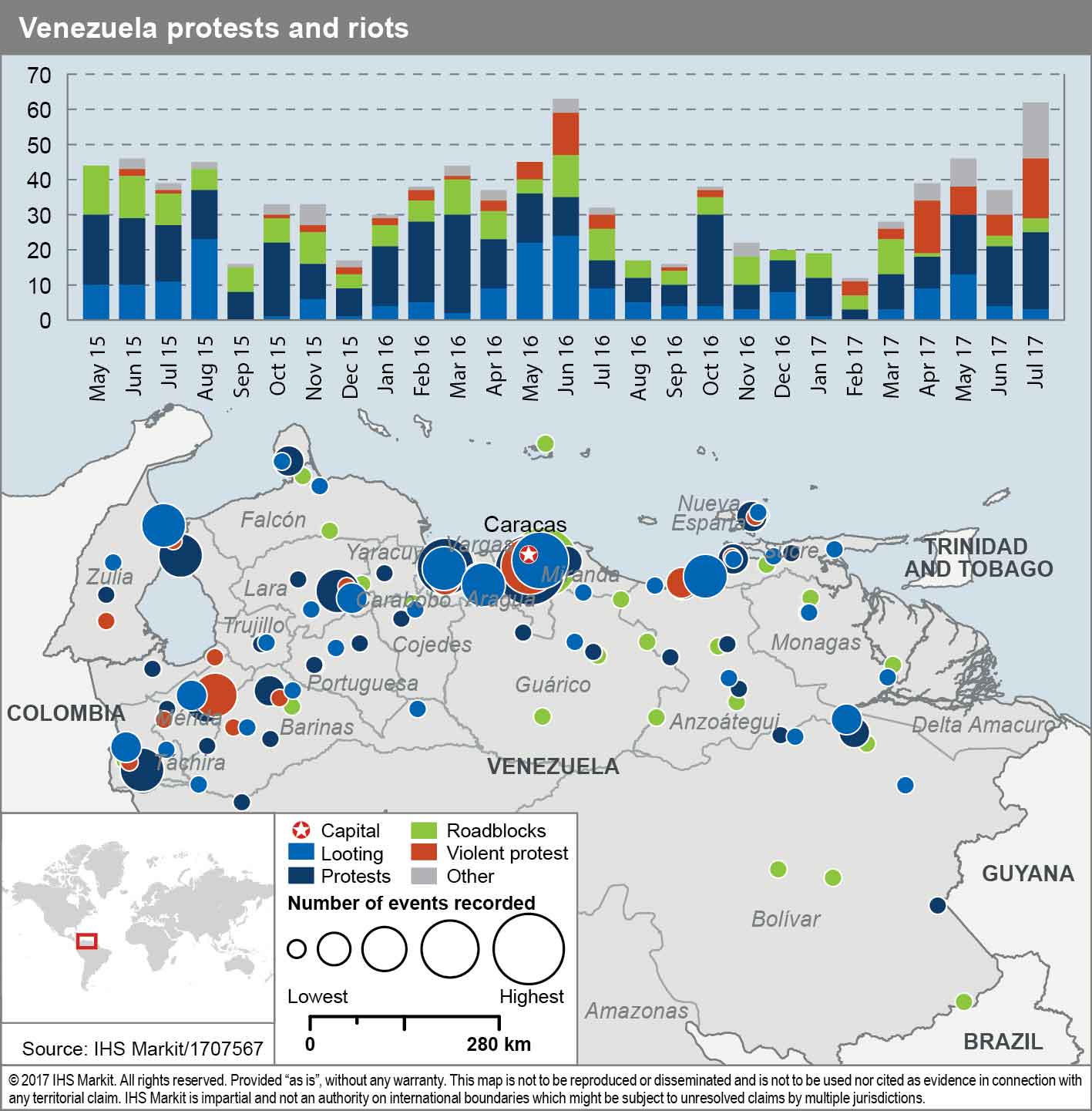

Venezuela on the brink

Venezuela’s political crisis deepened on 18 August when the new body charged with a controversial re-writing of the country’s constitution issued a decree declaring all institutions in the country subordinate to its authority. This comes amid a backdrop of five months of sustained mass protest and looting which have left more than 120 dead, instances of rebellion by some elements of the security forces and a dire economic dire situation (severe shortages of food and basic goods, an economy contracting by more than 7.4% and the world’s highest inflation rate in excess of 700%). The latest round of US sanctions, on 25 August, prohibits trade in Venezuelan debt and blocks state oil firm PDVSA from issuing bonds in the US; this will further destabilise the government of President Nicolás Maduro and increases the likelihood of a default in 2018.

Policy instability

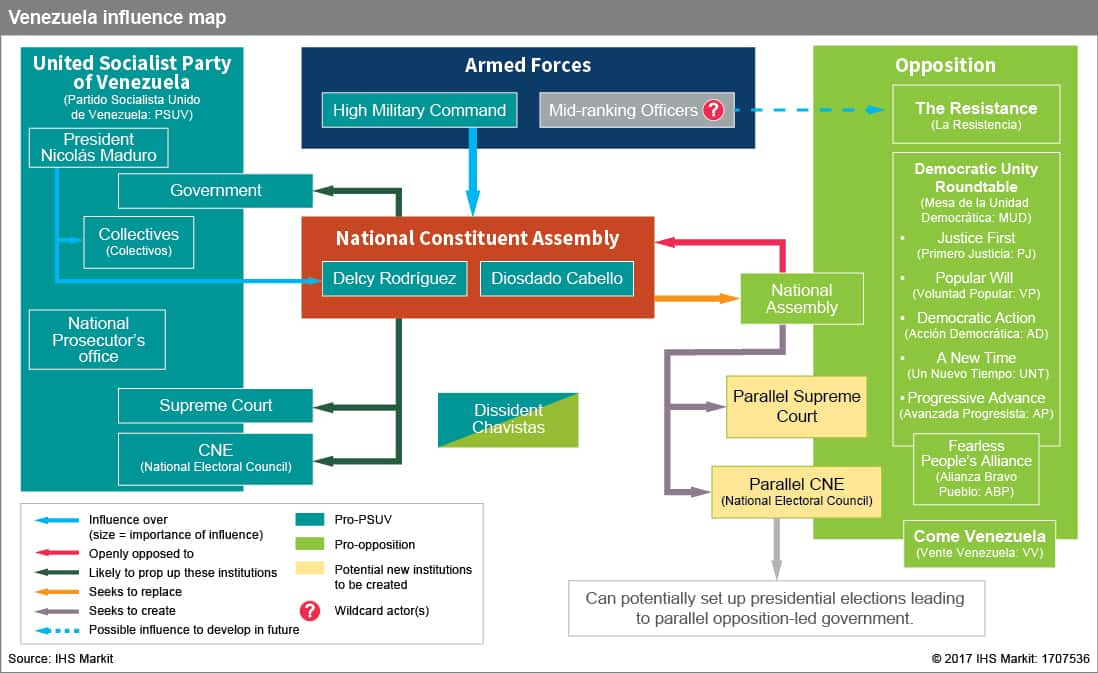

The National Constituent Assembly (ANC) is charged with rewriting the constitution within two years. Its recent assumption of the legislative authority of the opposition-controlled National Assembly effectively removes the remaining checks and balances on the government of President Maduro’s United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). That said, even the presidency has declared itself as subordinate to the ANC. This is effectively led by PSUV vice president Diosdado Cabello, who is very close to certain elements of the armed forces and the inner circle of former President Hugo Chávez.

The ANC is likely to use its newfound authority over budget, debt approval, and appointment powers to pursue the PSUV's agenda of the further political weakening of the opposition and state control over the economy. Regulatory uncertainty and contract risks are likely to rise across all sectors.

Indicators to watch: We will be watching whether the ANC legislates on price controls, issues tighter consumer protection regulations, or introduces expedited expropriation procedures; such measures would increase scrutiny and control of private businesses, especially those operating within the food and basic goods sectors. Other important decisions to watch include the ANC attempting to sell part of state oil firm PDVSA’s stake in heavy oil projects to Russia or China, in an effort to secure resources to honour short term debt commitments, or the ANC granting constitutional control of key sectors to the military, in an effort to guarantee their loyalty to the PSUV.

Evolving protests

The opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD) has declared itself in ‘civilian rebellion’ on grounds of article 350 of the Constitution, which in theory allows citizens to rebel against authorities aiming to change the Constitution by an “act of force”.

General fatigue by protesters and the MUD’s decision to participate in regional elections to select state governors in October 2017 have seen a reduction in civil unrest from early August but this is likely to spike again after the elections. At the same time, we have also seen cells of anti-government protesters known as “La Resistencia” (The Resistance) distance themselves from the MUD leadership and becoming increasingly violent as they confront the National Guard and the militias armed by the government, known as “Colectivos”. This has included occasional use of crude Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) against security forces attempting to break up protests.

Indicators to watch: Potential drivers of major escalations in protests include US sanctions on PDVSA’s oil exports to the US (which would worsen shortages of basic goods dramatically), a proposal to replace elections with a Cuban-style political system or moves to imprison further high-profile opposition leaders like (nominal) head of the National Assembly Julio Borges, former presidential candidate Henrique Capriles or independent leader María Corina Machado.

Coup risks

Patronage meted out to senior military officers, including control over an increasing proportion of both the legal and illegal economy, will probably ensure their loyalty for the time being. However, this will be tested as the impacts of targeted US sanctions on some of them begin to be felt. Furthermore, there is precedent in Venezuela (the 2002 coup) of the military intervening when protests reach a tipping point.

The risk of rebellion is much greater amongst mid-ranking officers, who do not benefit from such patronage and whose families will be feeling the impacts of ongoing shortages of basic goods. On 6 August, a mix of active and former soldiers shot their way into the Paramacay military base in Carabobo state, stole weapons and released a social media message calling for the military to stop supporting Maduro and demanding early elections. This follows the 27 June use of a helicopter by a rebellious police officer to target the Supreme Court and Ministry of Interior in Caracas.

Indicators to watch: Protest tipping points could include Maduro issuing unpalatable orders to the National Guard to violently repress unrest in the (traditionally pro-government) shanty towns, or a loss of control of areas around the main seats of government in western Caracas accompanied by hundreds of fatalities as a result of the MUD deciding to march towards the Miraflores presidential palace. The government losing political and financial support of Russia and China would further isolate the country, exacerbating the current economic crisis and creating the conditions for fractures between the ruling party and military.

Pathways to civil war?

Although currently unlikely, one potential scenario we are monitoring involves largely decentralised cells, many using the “Resistencia” moniker, organising themselves into military-style cells, procuring more sophisticated weapons and increasingly engaging in armed confrontations with security forces and “colectivos”. This threat would be enhanced significantly if they ally with rogue mid-ranking military and police officers, who could then supply weapons, training and mount more coordinated attacks. One further factor here is the potential for the ‘Colectivo’ militias to feel betrayed by the PSUV for not granting them sufficient power via the ANC, leading to armed confrontations with the National Guard.

Indicators to watch: More sophisticated IEDs against fixed military and police assets and government buildings; reports of attempts to exert a degree of territorial control over isolated pockets of strongholds (mostly likely in Mérida, Táchira, Vargas, Miranda, Aragua and Carabobo states).

Diego Moya-Ocampos is a Senior Risk Analyst within the Economics & Country Risk group at IHS Markit

Posted 29 August 2017

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fvenezuela-on-the-brink.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fvenezuela-on-the-brink.html&text=Venezuela+on+the+brink","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fvenezuela-on-the-brink.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Venezuela on the brink&body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fvenezuela-on-the-brink.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Venezuela+on+the+brink http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fvenezuela-on-the-brink.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}