Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Oct 04, 2018

US military drawdowns in sub-Saharan Africa

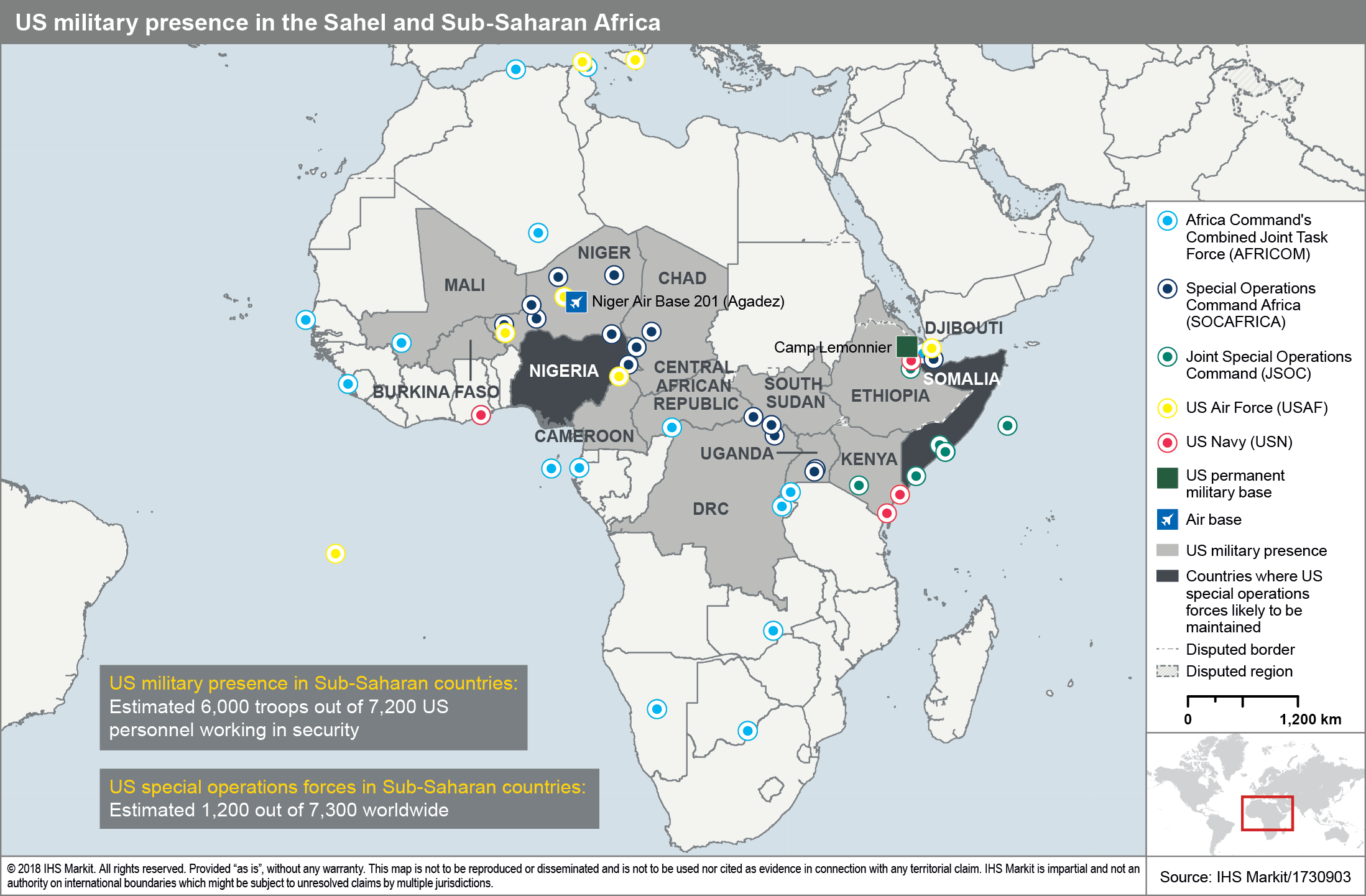

The US Department of Defense has proposed to close military outposts and seven out of the eight Special Operations Commands in sub-Saharan African countries, particularly in Central and West Africa, but likely excluding Somalia and Nigeria.

- The US Department of Defense's proposal to partially withdraw its Special Operations Commands is most likely resulting from a combination of the new US National Defense Strategy, which refocuses on "great power competition" from China and Russia, and a response to an attack against US soldiers in Niger.

- Underfunding of counter-terrorism operations is likely to hinder regional governments' stability and capability to counter insurgency and transnational jihadists in sub-Saharan Africa.

- The Special Operations Forces' redeployment is a likely indicator that the US is shifting its main focus on to the Horn of Africa, especially Somalia, whereas the European Union is maintaining its focus on the Sahelian region.

The Special Operations Commands (SOCs) have largely contributed in the US 'Train and Equip' program, which provides military training and equipment to ally countries. This program has been a key incentive for African leaders to participate in joint counter-terrorism (CT) efforts. According to official US data, the program accounted for approximately USD552 million in sub-Saharan Africa in the fiscal year 2016-17.

Deadly attack on US soldiers in Niger an immediate trigger

The New York Times reported on 2 September that the Department of Defense (DoD) had proposed to close military outposts and seven out of the eight Special Operations Commands (SOCs) in sub-Saharan African countries, particularly in Central and West Africa, but likely excluding Somalia and Nigeria.

A jihadist attack on 4 October 2017 against three US Special Operations Forces and five Nigerien soldiers on joint patrol in Niger's western Tillaberi region probably triggered the DoD's proposal. The United States has previously withdrawn its military forces following deadly attacks against forces deployed abroad. In 1993, then president Bill Clinton instructed US forces to withdraw from Somalia after 18 military personnel were killed, and in 1984, a US Marines force left the Lebanese capital, Beirut, after the deaths of 241 US personnel.

The decision to withdraw the troops has to be approved by US Secretary of Defense James Mattis and finalized by President Donald Trump, who would likely issue an executive order. This is facilitated by the fact that the US has no fixed military bases in sub-Saharan Africa aside from the permanent military base of Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti. In other countries of the region, the US will have negotiated Status of Forces agreements (SOFAs) with host countries on a bilateral basis to agree on the rules of jurisdictions and responsibility, allowing a level of flexibility on military personnel management. This includes the US using the host country's military installations, particularly airports.

Rethinking US Security Sector Assistance efficiency in sub-Saharan Africa

The proposed drawdown of forces primarily stems from the new US Congress-mandated National Defense Strategy (NDS). The strategy was devised in January 2018 by defense secretary Mattis and builds on the broader National Security Strategy outlined by President Trump.

Upon the release of an unclassified summary of the NDS, Mattis stated that the US would continue fighting jihadist threats but would increase resources on what he described as the "great power competition". The NDS summary specifically mentions long-term strategic competition with China and Russia, and the need to counter North Korea and Iran, requiring a streamlining of US armed forces to achieve a "more resource-sustainable approach".

Two studies commissioned by the US Office of the Secretary of Defense and the US military's Africa Command (AFRICOM) found that the Security Sector Assistance (SSA) appears to have had little or no net impact on reducing political violence in Africa. It added that "whatever 'success stories' might exist are relatively modest in their impacts on political violence, obscured by much larger amounts of inefficient spending or offset by counterproductive outcomes in other cases". These include "weaknesses in the ability of African states to maintain US-provided equipment" and "disseminate skills gained in US-sponsored training", the "misuse of funds by recipient states, and the repression of non-state actors that could be co-opted". Nevertheless, it noted that there was a "statistically significant" impact on political violence when SSA is conducted in conjunction with UN peacekeeping operations.

Impact on security and Foreign Internal Defense trainings

A reduction in the number of Special Operations Forces personnel in sub-Saharan Africa comes after the United Nations General Assembly approved on 30 June a 15% decrease in the UN Peacekeeping Operations budget proposed by President Trump's administration. The US president has increased pressure on the UN to reduce the peacekeeping budget from USD7.8 billion to USD6.69 billion in 2018-19, stating it was just the beginning.

African head of states and French President Emmanuel Macron have significantly pushed for a regional force in the Sahel through the G5 Sahel counter-terrorism force since 2014, made up of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger. This force was "welcomed" by the UN Security Council, which, however, failed - under US pressure - to approve a resolution on providing financial support. The 5,000 troop-strong G5 Sahel force has also not fully received the EUR414 million (USD479 million) pledged at the Brussels' donors' conference held on 23 February 2018.

Outlook and implications

Underfunding of CT operations, particularly in the Sahel where Al-Qaeda-affiliated groups operate, is likely to hinder regional governments' stability and capability to counter insurgency and transnational jihadists in sub-Saharan Africa. This was signaled when the G5 headquarters in Mali came under jihadist attack in June. Jihadist militants, primarily Al-Qaeda-affiliated groups, armed opposition groups, and government-sponsored militias, including in Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Niger, South Sudan, and Sudan, are likely to seek to exploit any security vacuum left by the US. Consequently, death, injury, and kidnap risks to military, UN, and non-governmental organizations' personnel, expatriates, and civilians are likely to increase in the six-month outlook following the withdrawal.

This risk is mitigated, however, by the fact that countries with the highest number of Special Operation Forces' troops are also the countries in which the US is likely to maintain and relocate its forces, such as Djibouti and Somalia. Instead, the Special Operations Forces' redeployment and the US cutting financing to joint CT operations in the Sahel are likely an indicator that the US is shifting its main focus on to the Horn of Africa, especially Somalia, whereas the European Union is maintaining its focus on the Sahelian region. An indicator of this would be greater US funding to the security mission in Somalia at the end of the secured financing period of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), which is ending in 2020. The US will probably maintain its plan to finalize the surveillance air base 201, south of Agadez, Niger, expected by late 2018. This is because the air base would allow the US to carry out air surveillance operations in Niger and neighboring countries, including Libya and Mali. The air base has been described by a US Air Force spokesperson as the "largest base-building effort ever undertaken by troops in the history of the US Air Force". This is also because it will likely be operated by the US Air Force rather than the Special Operations Forces. An indicator reducing the likelihood of jihadist attacks in the one-year outlook would be the US maintaining its training programs for beneficiary African countries.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-military-drawdowns-in-subsaharan-africa.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-military-drawdowns-in-subsaharan-africa.html&text=US+military+drawdowns+in+sub-Saharan+Africa+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-military-drawdowns-in-subsaharan-africa.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=US military drawdowns in sub-Saharan Africa | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-military-drawdowns-in-subsaharan-africa.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=US+military+drawdowns+in+sub-Saharan+Africa+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-military-drawdowns-in-subsaharan-africa.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}