Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Sep 21, 2018

Turkey still far from exiting currency crisis

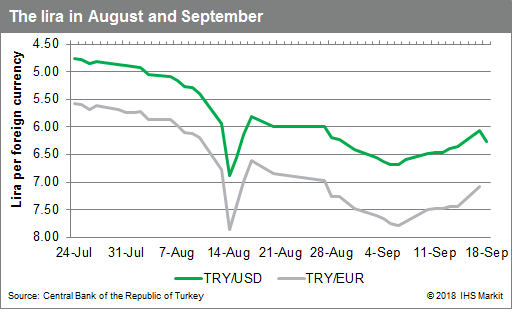

- The Turkish central bank provided a critical, sharp increase to policy rates in hopes of stemming the persistent depreciation of the lira. Immediate market reaction was positive, but in the following week, lira losses had begun again.

- President Erdoǧan remains a fierce critic of higher interest rates, but may have tacitly approved the move in order to stabilize markets and provide himself a scapegoat for the coming economic downturn.

- While the rate increases were welcome, they bring with them sharp downside risks of their own. The Turkish financial and corporate sectors are already facing difficult external repayment obligations because of the lira's depreciation. Now, high interest rates at home will further increase the costs of doing business, undercutting domestic demand and potentially triggering greater bankruptcies and loan defaults.

On 13 September, the Monetary Policy Committee of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (TCMB) raised most of its policy rates by 625 basis points, with the main rate - the one-week repo rate - moving to 24.0%. At the same time, the TCMB shifted the rate at which it funds the markets back from the overnight lending rate back to the one-week repo rate.

The rate increase came just hours after another of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's public attacks on higher interest rates, saying that they were a "tool of exploitation". He, instead, blamed high inflation on missteps by the TCMB, and that these high interest rates were actually causing high inflation.

This rate increase was a welcome and necessary first step towards exiting the ongoing Turkish lira crisis. The immediate market reaction was one of relief, with bond spreads narrowing and the lira rallying against the US dollar and the euro. The degree to which the TCMB increased the repo rate was a positive surprise, a more aggressive action to get in front of annual inflation than IHS Markit and many observers had anticipated. However, the TCMB's action was not only important in terms of how high the rates were compared to inflation, but the simple act of raising the interest rates aggressively was meant to be a signal that it was indeed independent of Erdoǧan, a point reiterated by Finance Minister Berat Albayrak following the rate hike announcement.

It is important to note that this interest rate increase is only a bare minimum, first step to exit the current crisis. There is a high probability that the lira will once again begin to depreciate rapidly after only a temporary rally, potentially forcing the Bank to raise interest rates even further at later policy meetings. Already, at the beginning of the following week, the lira was depreciating once again. Confidence in the TCMB's institutional integrity has deteriorated over a number of years and one rate decision is not enough to erase all of these building doubts about its political independence. In particular, it is likely that this rate increase was taken only after securing Erdoǧan's tacit, behind-the-scenes approval. The president likely saw that a rate increase was the fastest way to achieve market stability in the short term, and allowed the TCMB to take action. But, by continuing to publicly decry the actions, he is positioning himself to deflect blame for what will be a negative impact on domestic demand.

To rebuild financial-market stability, the Bank must, at a minimum, maintain these high interest rates for more than a month or two, while also taking other actions to maintain defensive monetary policy. Although President Erdoğan will continue to decry high interest rates, it will be important that he limits his opposition to rhetoric. Should these actions, or the resulting negative impact on domestic demand growth, trigger a more tangible push to find a scape goat by Erdoğan - perhaps an attempt to push out TCMB Governor Murat Çetinkaya or members of the Monetary Policy Committee or to impose penalties on the governor or the committee members - another currency crisis could develop as confidence in institutional integrity is once again undermined.

Higher interest rates are not without their own substantial real downside risks. Most notably, the higher domestic interest rates further jeopardize the health of Turkish banks and corporations. Domestic currency lending will be undermined by the increased costs associated with the higher interest rates. Corporations will be in greater jeopardy because of these higher interest rates that will make repayment of their debt more difficult. With higher interest rates undermining domestic demand, we expect corporate bankruptcies to rapidly rise. As the banks curtail their domestic credit growth because of higher costs - and a lack of new financing from abroad - and the corporates increasingly entering bankruptcy, non-performing loan ratios within the Turkish banking sector will rapidly mount. A rapid deterioration in the health of the banking sector or the corporations could trigger another round of lira losses.

The immediate impact of lira instability and higher interest rates on the real economy will be a short recession, one that may have already begun in the third quarter of 2018 and that is expected to extend until the second quarter of 2019. Sharp losses of household consumption and gross fixed investment will drag down overall GDP during this time.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fturkey-still-far-from-exiting-currency-crisis.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fturkey-still-far-from-exiting-currency-crisis.html&text=Turkey+still+far+from+exiting+currency+crisis+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fturkey-still-far-from-exiting-currency-crisis.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Turkey still far from exiting currency crisis | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fturkey-still-far-from-exiting-currency-crisis.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Turkey+still+far+from+exiting+currency+crisis+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fturkey-still-far-from-exiting-currency-crisis.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}