Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Aug 23, 2018

South Africa expropriation risk

The South African parliament began its five-week-long third term on 14 August. During this period, it is expected to redraft the Expropriation Bill in line with the ruling African National Congress (ANC) party's decision on 31 July to amend the property clause in the Constitution to allow for the expropriation of land without compensation.

- Policy instability in South Africa relating to property rights is likely to remain elevated over the one-year outlook, although wholesale expropriation without compensation is very unlikely either before or after the 2019 election.

- Uncertainty over property rights is likely to deter fixed investment, limit government revenue, and lower overall GDP growth, and ultimately could trigger further downgrades by international credit rating agencies such as Moody's during 2019

- Banking-sector impairment will increase, albeit from a low base, and credit growth is likely to decline.

Under increasing electoral pressure from opposition party the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), South African President Cyril Ramaphosa and the ruling ANC's National Executive Committee (NEC) decided on 31 July to support a parliamentary motion to amend Section 25 of the Constitution, dealing with property rights. Uncertainty over the implications of the new policy on property rights is likely to remain until the State of the Nation Address (SONA), in which the president usually sets out a broad policy agenda. The next SONA will take place after the 2019 elections, expected to take place by May at the latest.

ANC's radical economic transformation agenda

In December 2017, at the ANC conference, the ruling party moved to counteract the increasing popularity of the leftist EFF. It adopted a resolution that the ANC government should undertake land expropriation without compensation (EWC), to accelerate land redistribution and ultimately to achieve radical economic transformation. This resolution was among several forced through by an ANC faction supporting former president Jacob Zuma and his ex-wife's candidacy to succeed him both as party leader and national president. While Ramaphosa won the party leadership contest at the conference, he inherited policies which he and his supporters within the ANC largely opposed. Conference resolutions are binding on ANC officials in government. Several controversial conference resolutions were passed, including plans for expropriation of land; the decision to downgrade diplomatic relations with Israel; to withdraw from the International Criminal Court (ICC); and to nationalise the South African Reserve Bank (SARB), the central bank.

The 31 July decision by the ANC's NEC (the party's highest decision-making body between conferences) pre-empts the outcome of a parliamentary Constitutional Review Committee (CRC) process that has been under way since June. The CRC initially was established to conduct popular consultations on proposed constitutional changes but had become a useful campaign vehicle for EFF leader Julius Malema, who exploited membership of CRC and the land issue to increase support for the EFF across rural constituencies, particularly in the Eastern Cape and Limpopo provinces, which accounted for a quarter of the ANC's 11.4 million votes in the last general election in 2014. After such momentum, the EFF's voting share now will determine whether the ANC can retain a 50% majority in parliament, enabling it to form a government without requiring a coalition. Withdrawing the draft Expropriation Bill currently before parliament and inserting wording that makes EWC possible represents a convenient tool for the ANC to seek to stem the EFF's progress by demonstrating its positive intent on the issue of land redistribution.

ANC's likely course of action

IHS Markit sources report that Ramaphosa believes that the ANC's new policies could undermine investors' confidence. Since taking office in February, he has used the parliamentary process to delay decisions in respect of the conference resolutions on the SARB, Israel, and the ICC. However, Ramaphosa is supporting the resolution to change the constitution on the emotive issue of land expropriation. We assess this to be an effort to unite his fractured party while seeking to recapture young and rural voters from the EFF. We expect that he is very likely to temper such support after taking office with a fresh mandate following the 2019 poll, which the ANC appears very likely to win outright, even though it is unlikely to retain the 62% voting share achieved in 2014.

In the meantime, the CRC's work is likely to be drawn out as the committee assesses and documents public submissions on the EWC issue, prior to presenting its findings to the legislature for discussion. This is likely to take at least three months. Parliament must then discuss and establish the wording for a new property clause in the constitution, which is likely to take a further three months or more. Ramaphosa is likely to encourage this process to proceed slowly, extending over the coming months as this stance, and any ensuing court challenges to the amendment, will buy him time. Given these pressures, Ramaphosa is likely to push for an early election date, potentially in April 2019, with voting almost certainly no later than May. If he then won a clear overall majority, this would give him a strong electoral mandate, better positioning him to influence the drafting of new legislation in a way that emphasised safeguards and reduced the risk of widespread land seizures. In December 2017, the ANC's resolution on land stated that its implementation must ensure that it does not undermine future investment, damage food security, or cause harm to other sectors of the economy. The resolution further states that interventions should focus on state-owned land, prioritising the redistribution of vacant, unused, and under-utilised land, land held for speculation, and highly-indebted land. The resolution emphasises that strong action should be taken against those who occupy land unlawfully. While Ramaphosa could emphasise these important safeguards in the lead-up to the elections, he is unlikely to do so, as this would risk undermining his support inside the ANC and benefit the opposition EFF. He is very likely to emphasise the safeguards during his first post-election SONA in 2019 instead.

Economic outlook

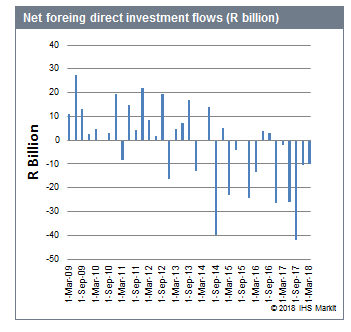

Uncertainty over property rights - at least until May 2019 - is a particularly negative indicator for South Africa's residential and commercial property market. Additionally, any positive turnaround in net foreign direct investment flows, which have been net negative since 2014 (see graph), appears highly unlikely. Instead, South Africa has become excessively dependent on highly volatile portfolio inflows to finance its structurally embedded current-account deficit. These flows are subject to reversal, reflecting changing emerging-market sentiment and the country's local-currency credit risk ratings.

South Africa is highly exposed to portfolio outflows. Latest statistics produced by the SARB show that foreign holdings of South African rand-denominated debt amounted to USD57.6 billion at end-2017, while foreign-currency-denominated debt held overseas amounted to USD26.7 billion. South Africa suffered an estimated USD5.3 billion net portfolio outflow involving debt investments during May-August in response to higher interest rates in the United States and the increasingly controversial populist ANC rhetoric. The latter is viewed by investors as putting the country's growth prospects and current domestic currency credit risk rating at risk. Severe instability in the Turkish lira and Turkish debt during August triggered a second-round sell-off of South African financial assets and the rand. During the month, the rand's exchange rate depreciated over 8% against the US dollar. Higher inflation caused by currency weakness comes at a time when South Africa was already facing the strong possibility of recording another weak GDP growth figure for the second quarter of 2018. If negative, this would imply that South Africa has entered a technical recession. IHS Markit is of the view, however, that GDP growth increased by a very small real seasonally adjusted annualised rate of growth of 0.4% during the second quarter, averting a formal recession. However, the risk to this outlook remains highly skewed towards the downside.

The weak growth profile is particularly challenging for South Africa's fiscal finances moving forward. The South African budget assumes a real GDP growth rate of 1.5% for 2018. IHS Markit is of the view that growth will be lower, at around 1.2-1.3% for the year. For 2019, the National Treasury projects a real growth rate of 1.8%, but IHS Markit projects real GDP growth of around 1.5%. The lower growth outlook, combined with less tax buoyancy, will act as a drag on fiscal revenue flows during the upcoming fiscal year. Furthermore, expenditure overruns due to the above-budget negotiated public-sector wage increases, financial constraints at state-owned entities, and the introduction of free education could all add to the deficit.

The uncertainty over property rights, which in IHS Markit's view will deter fixed investment, limit government revenue, and lower overall GDP growth, ultimately could trigger further downgrades by international credit rating agencies such as Moody's during 2019 (the only agency that still assigns investment status to South Africa's local-currency-denominated debt). Under this outcome, IHS Markit forecasts that the South African rand's exchange rate could weaken by another 10-15%, while GDP growth for 2019 would contract to -2% as both inflation and interest rates spike upwards. The appetite of local investors to absorb foreign-owned government bonds will determine whether capital controls would need to be introduced under such a scenario. IHS Markit considers the risk of an International Monetary Fund bail-out to be limited, given that the rand's exchange rate would be an important balancing factor. As in Angola, Mozambique, and Zambia, which experienced external liquidity pressures during 2014-15, the weaker South African rand will stifle import demand, shielding South Africa's foreign-reserves holdings while higher domestic interest rates will control inflationary pressures.

A strict adjustment to the government's spending ceiling over the medium term could nonetheless prevent a downgrade by Moody's. Below-budget capital expenditure, the use of the government's large contingency reserves, some partial privatisation initiatives for state-owned entities such as South African Airways, and downsizing the public-sector labour force could increase the likelihood of this more-favourable outcome. This scenario also assumes some greater clarity regarding future property rights as the year progresses.

Financial-sector outlook

IHS Markit assesses that credit growth is likely to decline, while banking-sector impairment will increase, especially in relation to land or property used as collateral by commercial farmers, in the unlikely event that the ANC pursues wholesale EWC.

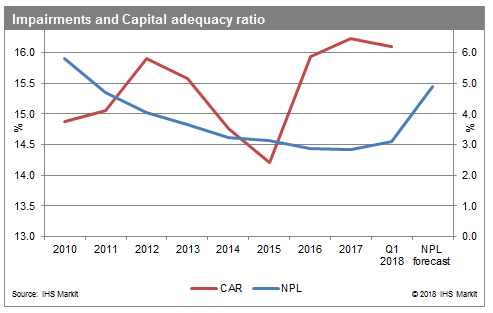

According to the SARB, mortgages in the banking sector amounted to ZAR1.4 trillion (USD98 billion) or 39% of the total loan book at end-2017. We estimate that the banking sector's exposure to agriculture debt is ZAR160 billion. EWC would make commercial banks vulnerable to an increase in impairments as bank borrowers who own commercial farms and/or farm houses or land that has been used as collateral effectively could end up with an unsecured loan and loss of the underlying asset, making them likely to default. In addition, we expect reduced credit growth as banks will be reluctant to extend new credit, especially to the agricultural sector, while policy uncertainty remains. Banking-sector impairment grew from 2.8% in December 2017 to 3.1% in January 2018, albeit from a low base, which was attributed to the implementation of the IFRS9 accounting standard: the sector's capital adequacy ratio declined slightly from 16.3% to 16.1% over the same period but remained strong overall. With an assets-to-GDP ratio of about 110% and a credit-to-GDP ratio of 79.8% as of the first quarter of 2018, the banking sector is large relative to the size of the South African economy, suggesting that any future financial stress involving one or more of the big five banks (which collectively account for almost 90% of total sector assets) would place a significant burden on government finances.

Other lenders will also be affected by a wholesale EWC. The state-owned development bank, Land Bank, is likely to be the worst affected. Land Bank has a mandate is to provide financial assistance to commercial farmers and agricultural businesses in line with government directions. During the presentation of its end-2017 results in Johannesburg on 21 August, Land Bank chairman Arthur Moloto indicated that it has ZAR16.2 billion exposure to long-term loans and loans secured by mortgages. Moloto added that, if this loan book portfolio were included in the government's EWC plan, it would leave the institution with "a call to immediately repay loans amounting to ZAR9 billion", an obligation that would be challenging for an institution with cash resources of ZAR2.5 billion. Should the bank fail to honour such initial obligations, it would lead to its other creditors demanding repayment of around ZAR41 billion. We expect that the bank would be rescued by the government. In any case, Land Bank is not in immediate jeopardy: it reported a capital-adequacy ratio of 17.3% for the year ended March 2018 versus 17.7% in March 2017, while its non-performing loans (NPLs) ratio fell to 6.7% from 7.1% over the same period.

Outlook and implications

While the ANC is very unlikely to embark on wholesale EWC, the proposed changes in constitutional legislation are likely to cause policy uncertainty over the one-year outlook. They have already placed the rand under pressure, with the resulting increase in inflation - and likely policy moves to tighten monetary policy - increasing downside risks for the economy, which faces the risk of entering formal recession. We also expect reduced credit growth as banks will be reluctant to extend new credit, especially to the agricultural sector, while policy uncertainty remains. Banking-sector impairment is also likely to increase, albeit from a low base. IHS Markit assesses that a Moody's downgrade may be avoided in 2019 if the government meets its spending targets, downsizes the public sector, and state-owned enterprises' financial position improves. This would avoid the worst-case scenario of large-scale portfolio outflows, further currency weakness, significant increases in interest rates, and a clear move into recession.

South Africa is highly unlikely to follow Zimbabwe's precedent with land grabs, which included extended international default. Instead, the government is only likely to consider implementing some ANC conference resolutions after the 2019 elections. This will allow it to limit the EFF's electoral gains, while attempting to progress slowly with any actual expropriations. Ahead of the polls, the ANC is mostly likely to make token gestures as progress towards broader land reform, such as the announcement of negotiated deals with land owners or specific plans for state-owned land resources where demand is most acute. However, post-elections, if the EFF makes large-scale gains preventing an ANC outright majority, this would be a significantly adverse risk indicator, as the need for coalition arrangements would limit Ramaphosa's scope to temper EWC implementation.

In the one-year outlook, continued EWC rhetoric and possible changes in investors' sentiment towards emerging markets could place the rand under pressure. The resulting increase in inflation, likely policy moves to tighten monetary policy, and continued policy uncertainty until mid-2019 heighten risks of South Africa entering formal recession. Uncertainty around the extent of EWC will reduce credit growth, while banking-sector impairment is likely to increase, albeit from a low base. IHS Markit assesses that a Moody's downgrade in mid-2019 would most likely trigger the worst-case scenario of large-scale portfolio outflows, further currency weakness, significant increases in interest rates, and a clear move into recession by the third quarter of 2019. IHS Markit's base case is that this scenario will likely be avoided, if the government revises its spending targets, downsizes the public sector, and state-owned enterprises' financial position improves. The government has already made commitments to fiscal consolidation, and these are likely to be reinforced in the Mid-Term Budget Statement in late October.

This report was written by IHS Markit economists Thea Fourie, Joyce Silungwe , and Langelihle Malimela

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsouth-africa-expropriation-risk.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsouth-africa-expropriation-risk.html&text=South+Africa+expropriation+risk+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsouth-africa-expropriation-risk.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=South Africa expropriation risk | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsouth-africa-expropriation-risk.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=South+Africa+expropriation+risk+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsouth-africa-expropriation-risk.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}