Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jun 29, 2018

Sahel terrorism risk assessment

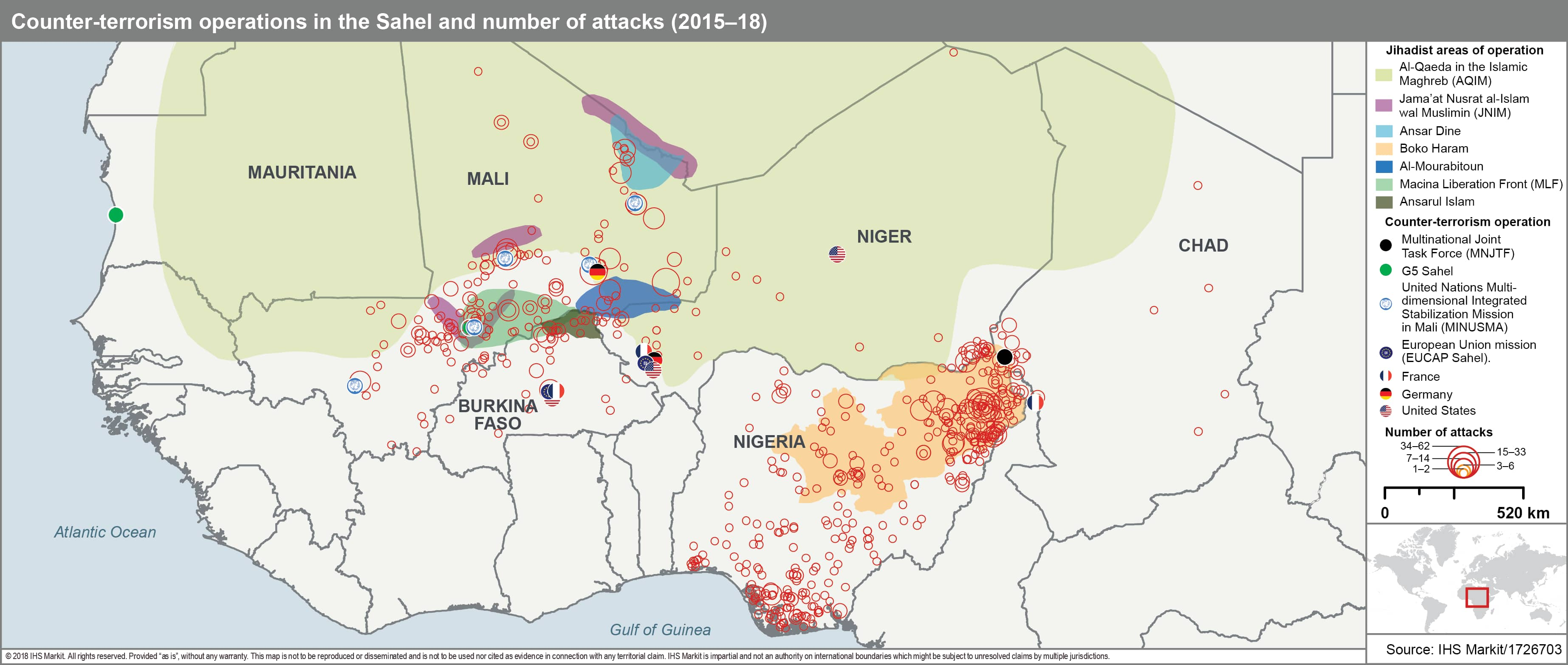

Our data analysis has identified key patterns in jihadist terrorism in the Sahel regional countries of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Nigeria since 2015.

- IHS Markit's intelligence event database demonstrates a steep rise in jihadist terrorism from 2015 to 2017, with the overall number of attacks and fatalities in Sahel countries increasing by 80.2% and 62.5% respectively.

- The increase in attacks is accounted for by the merger of local jihadist groups, representing different ethnic groups, under the banner of Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), as well as the territorial demise of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq since mid-2017.

- JNIM is likely to increasingly shift its target set across the Sahel, focusing less on soft targets such as hotels and similar venues frequented by expatriates, and more on national and international government and security forces.

Our data shows an overall rise in the rate of jihadist attacks across the six Sahel countries of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Nigeria since 2015. The number of attacks was 163 in January 2015, which rose to 781 in May 2018.

Al-Qaeda in Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has successfully expanded its presence in the Sahel region. This was predominantly facilitated by the merging of jihadist groups' activities in the Sahel and encouraged by the territorial demise of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria as of mid-2017, which has led Islamist militants to seek new destinations to relocate to. The political instability in Libya provided the necessary conditions for the transit of both jihadists and arms into the Sahel, facilitated by the country's poorly guarded desert border. Moreover, AQIM has taken advantage of existing trafficking routes in desert and forest areas across the region.

Counter-terrorism operations encouraging pooling of

jihadists under JNIM

IHS Jane's Terrorism and Insurgency Centre (JTIC) notes that, from

2015 to 2017, the overall number of attacks and fatalities in these

Sahel areas increased by 80.2% and 62.5%, respectively. The

increased frequency of attacks in the Sahel region indicates that

several jihadist groups are co-operating. This is most probably due

to the protests for a peace accord in Mali that jihadists intend to

prevent and to the stepping up of counter-terrorism operations in

Sahel, such as the French military Operation 'Barkhane', and the

joint force of the group of five Sahel countries (G5 Sahel; Burkina

Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger).

In March 2017, four smaller jihadist groups operating in the Sahel, representing different ethnic groups, merged into one entity, Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), to combat counter-terrorism forces. JNIM, which pledged allegiance to AQIM, gathers members from different ethnic groups, providing AQIM with unprecedented geographical and social reach within the Sahel. This has allowed it to expand its support networks, including social support for recruitment, financial support, and the use of criminal networks. For instance, in 2012, Ansar Dine's leader, Iyad Ag Ghali, who is now heading the JNIM coalition, co-operated with the Malian Tuareg separatist group, Mouvement national pour la libération de l'Azawad (MNLA), to take control of the Malian northern region. The MNLA and Ansar Dine, however, split due to the divergence in motivations and beliefs. While Ansar Dine aimed to establish an Islamic state in the Sahel countries, the MNLA had a secular separatist goal. Ansar Dine has drawn from ethnic conflicts in Mali since 2012 by ensuring Songhay and Fula groups' opposition to Tuareg rule, leading to the MNLA's loss of control of the city of Gao in favor to Ansar Dine.

Our data shows that, since 2017, AQIM has maintained a constant level of attacks and that attacks by AQIM are immediately followed by larger and more frequent attacks by JNIM. The resemblance in attack type and close timeline suggest that AQIM is directing JNIM. Similarly, attacks by JNIM are followed by the Islamic State's attacks. However, this suggests that the Islamic State is most likely seeking to reinforce its presence in the Sahel but has more difficulty in doing this than JNIM, mainly because of the latter's advantage in having established a wider local network of affiliates. To be able to maintain this local network, AQIM is likely increasingly drawing on local grievances emphasizing the government's preferential treatment of foreign companies at the expense of the local population.

Changing priorities

AQIM made several statements in 2017 and 2018 mainly through its

media agency, Al-Andalus, threatening countries engaged in

counter-terrorism operations, but also threatened Western

companies, particularly French, working in North Africa and Sahel

countries that they were now "legitimate targets for the

Mujahedeen". AQIM accused international companies active in the

Sahel of stealing the local wealth and maintaining the status quo,

contributing to the spreading of "poverty and unemployment".

In accordance with AQIM's threats, IHS Markit's intelligence events demonstrate a clear shift in target set for jihadist attacks across the Sahel, focusing less on soft targets such as hotels and similar venues frequented by expatriates, and more on national and international government assets and security forces. These are predominately French counter-terrorism Operation Barkhane and United Nations bases.

Outlook and implications

JNIM is likely to continue focusing its attacks on government and

security forces -national and international - in and around Sahel

urban areas in the six-month outlook, with the objective of testing

the response and identifying new vulnerabilities. These are likely

to include both simpler guerrilla tactics preferred by AQIM's local

affiliates, such as shooting ambushes and roadside improvised

explosive devices (IEDs) targeting security forces' convoys, as

well as more complex attacks targeting government and military

bases, potentially through infiltration, not only in capitals, but

also less well-defended cities. The G5 Sahel headquarters in

Mauritania and operational outposts are likely to present

particularly attractive targets, given reports of financial

constraints giving rise to insufficient manpower and resources.

Mali is likely to remain JNIM's organizational base mainly due to the continued absence of state control in the country's north, which hinders progress on implementing a peace agreement between the government, ethnic factions, and armed groups.

Meanwhile, the proximity of military bases to airports entails elevated shoot-down risks for military and UN civilian aircraft, as was the case in a 14 April 2018 attack in Timbuktu. Similarly, there is a high risk of collateral, if not targeted, damage to parked aircraft.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsahel-terrorism-risk-assessment.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsahel-terrorism-risk-assessment.html&text=Sahel+terrorism+risk+assessment+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsahel-terrorism-risk-assessment.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Sahel terrorism risk assessment | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsahel-terrorism-risk-assessment.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Sahel+terrorism+risk+assessment+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsahel-terrorism-risk-assessment.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}