Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jan 02, 2020

Political risks and capital flows in 2020

It is common to assume that the composition, direction, and volume of capital flows to emerging markets are determined by global 'push' factors. Since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-2009, quantitative easing and low interest rates in the advanced economies have pushed investors hungry for yield into emerging market bonds, equities, and local currency markets. Yet, political risk is increasingly important, as demonstrated by the on-going trade war between the US and China. During 2020, it is even more likely that domestic 'pull' factors will be the focus of attention, in terms of the country-level composition of inflows and their sensitivity to changing political risks. Notable trends include sudden and onerous changes in government policy following elections, growing political control over central bank policy, and the knock-on effects of government's failing to reform public finances during periods of stronger economic growth. The importance of these factors was highlighted in a recent study by the Bank for International Settlements. This concluded that counter-cyclical flows in capital are driven primarily by factors within emerging markets, and therefore it is no longer possible to generalize assumptions about the business cycle properties of capital flows and their relationship with global push factors.

Our country risk team discusses three markets to watch during 2020, where capital flows; primarily direct foreign investment (FDI), portfolio inflows, and bank lending, will be particularly sensitive to political risk.

Slowing growth and India's exit from major regional trade negotiations is reducing FDI inflows, indicating that the successful advancement of President Modi's liberalization agenda will be vital for facilitating inward investment. Deepa Jumar, Senior Analyst

Q: Will the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) still advance now that India has withdrawn?

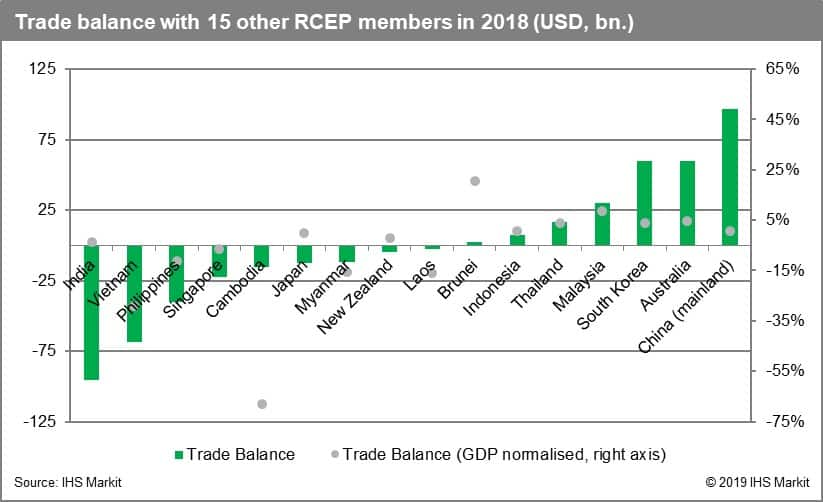

First, we need to understand why 16 Asian countries decided to embark on a free trade agreement. The RCEP has been in the works for a few years but the momentum increased as the trade war between the US and China escalated, as Asian countries began to focus more on trade within the region. There is enough evidence to show now that Asia is trading more within the region. In fact it's the second largest trading bloc in the world after the European Union. If India were to join, RCEP would represent around 30% of global GDP, making it the largest trading bloc in the world. With India having already left in November, the other RCEP members have stated that they will sign the agreement by February 2020. However, India remains the key attraction for RCEP members, so a delay is likely as RCEP members would continue to face the same trade-related issues with India like high tariffs and preference for domestic industries. So RCEP may not go ahead, but the momentum now is intra-regional trade within Asia.

Q: Is there anything we can look out for to indicate that India will join RCEP?

A few interesting indicators have appeared over the last few weeks. First was that Japan's Prime Minister Abe Shinzo is trying to renegotiate India's entry. He may travel to India in the coming months to reposition RCEP in a way that is favorable to India. We've also see media reports in China suggesting that it's important to renegotiate with India and keep them committed to the agreement. But the big question here is why India does not want to join RCEP. And there are two key reasons. First that India is weak domestically and stands to lose the most from RCEP, particularly as it has a much larger trade deficit than China. Given RCEP now focuses on free trade in goods, India would want to utilize its comparative advantage of free trade in services. Otherwise, the India market is vulnerable to Chinese dumping. So there are two indicators to look out for. First, if RCEP includes India's demand for an automatic safety mechanism in the form of taxes on Chinese imports. And second, if RCEP broadens its mandate to services, such as by improving the provision of visas for professionals, then this would increase the likelihood of India joining RCEP.

Q: How will India navigate its slowing economy in 2020?

This is the key policy risk in 2020. IHS Markit has already downgraded India's 2019/20 GDP growth outlook to 5.8%. The next year looks a little mixed. The government is saying that the slowdown is cyclical, but there is evidence that direct foreign investment inflows are slowing down. The government has responded by reducing the corporate tax rate. However, most important will be pushing ahead with a partial liberalization drive and expediting land and labor reforms to make the business environment more attractive for foreign investment. Key sectors for liberalization are construction, manufacturing, and electronics.

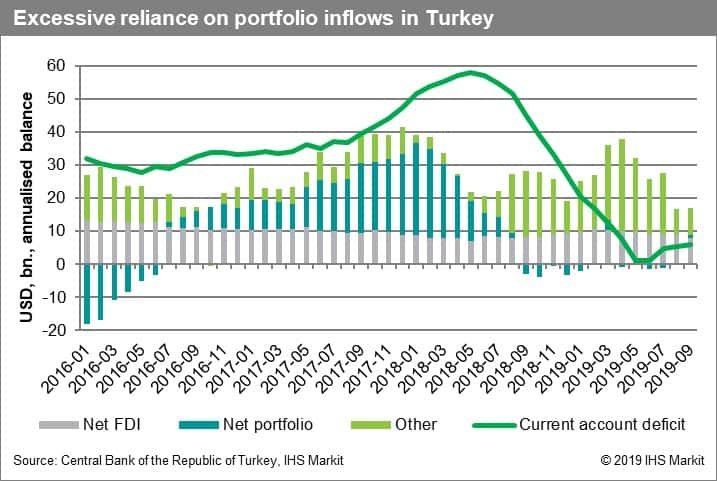

Turkey's continued excessive reliance on more liquid portfolio inflows increases the country's sensitivity to the prospect of US sanctions and political control over monetary policy. Ege Seckin, Senior Analyst

Turkey has a chronic current account deficit that is financed primarily by portfolio inflows as opposed to more stable channels like FDI. Around 2013, Turkey's political risk premium increased significantly because of a range of issues from government stability, terrorism, and Turkey's proximity to the Syrian war. Now I should note that the current account deficit turned into a surplus in 2019, but this was largely the result of an economic recession that suppressed domestic import demand and is therefore a temporary trend.

Two key indicators to watch for the direction of capital flows in Turkey are Credit Default Swaps (CDS) and the value of the Lira, the local currency. Both of these indicators have fluctuated in Turkey in recent years, because of political risk and macroeconomic factors.

Q: What are the key domestic risks to watch in 2020 and what will be the impact on portfolio inflows?

The Turkish economy is starting to grow again in Q4 2019. This has also meant that the current account is going back into deficit and is likely to widen as we head into early 2020. Even though net portfolio inflows are struggling to remain inward, FDI is also struggling, suggesting a more systemic risk averse sentiment among investors towards Turkey. For instance, Turkey is already USD3.4 billion down on net FDI inflows in 2019 compared with 2018, and we think this trend is very likely to continue into 2020.

Turkey hasn't taken any bold steps to rectify structural economic issues, and we are seeing the repeat of previous mistakes that led to the Lira currency crisis in 2018. For instance, currency swap markets were shut down earlier in the year to prevent a run on the Lira in the lead up to the local elections. Also, we understand that the authorities instruct private banks on what deposit interest rates they ought to use. All these unconventional measures are intended to protect the Lira without implementing interest rate hikes. So, political control over monetary policy will be a key risk in 2020, particularly the government's aversion to increasing interest rates.

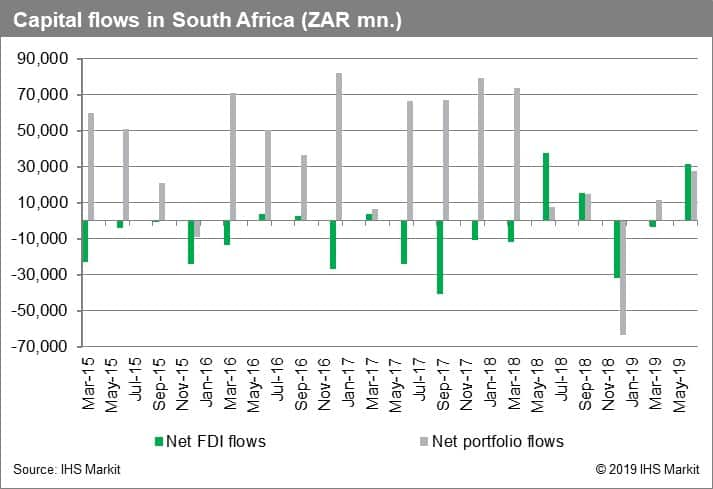

Investor uncertainty around the ruling African National Congress (ANC) party's radical economic agenda and the concentration of portfolio inflows within indebted state-owned entities increases South Africa's vulnerability to capital flight. Langelihle Malimela, Senior Analyst

Q: Economic data released earlier this month indicated that the South African economy had further contracted by 0.6% in the last three months. Are the ANC's radical economic policies still likely to advance and what will be the impacts on capital flows during 2020?

South Africa's local currency the Rand operates on a free-floating exchange rate, so is very sensitive to domestic as well as global political movements. So, the US-China trade war has also affected capital flows to South Africa for much of 2018 and 2019. The expectation in 2018 that Moody's would downgrade South Africa's rating had a significant impact on encouraging portfolio outflows, and fixed investment was also poor for a long time - especially under the leadership of former president Jacob Zuma. There has been a turnaround under Cyril Ramaphosa. But this is largely not greenfield investment but capital goods transferred within large multinationals from parent companies abroad. The government has a plan to raise USD100 billion in foreign investment up until 2023 and has held investor conferences supporting this that have been pretty well received.

However, the prospect of a ratings downgrade is largely dependent on domestic political factors. Especially the ruling Africa National Congress (ANC) policy mandate for 2020, especially concerning several radical economic policies that will be put to the ANC's General Council in July 2020. That meeting will act as a mid-term policy review for the party, and key policies will include the nationalization of the Reserve Bank (the central bank) and the expropriation of land without compensation. These will come back to prominence as Ramphosa's opponents use these policies to test whether there is support for a vote of 'no-confidence' against the President. Now such a vote would be very unlikely to succeed, but Ramaphosa will need to make some accommodation, causing increased policy uncertainty that will have an impact on portfolio inflows.

Listen to the full version of our webinar on Political Risk and Capital Flows in 2020.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolitical-risks-and-capital-flows-in-2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolitical-risks-and-capital-flows-in-2020.html&text=Political+risks+and+capital+flows+in+2020+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolitical-risks-and-capital-flows-in-2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Political risks and capital flows in 2020 | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolitical-risks-and-capital-flows-in-2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Political+risks+and+capital+flows+in+2020+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolitical-risks-and-capital-flows-in-2020.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}