Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jan 18, 2019

Policies of expropriation and prescribed assets in South Africa

- South Africa's long-term growth prospects could trail down to around 0.5%-1.0%.

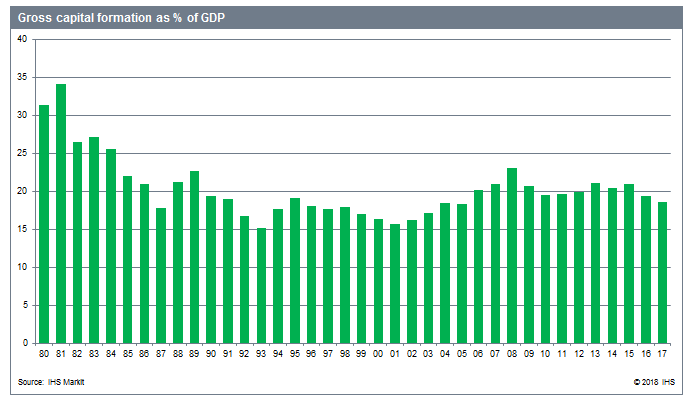

- Proposed policies by the African National Congress (ANC), which include expropriation of land without compensation and prescribed assets for pension funds, could jeopardize future capital accumulation and productivity growth.

- Legal action by opposition parties and civil society could delay policy implementation

History shows that most nations that adopted it embarked on the expropriation of land without compensation with a strong belief that it would be done within a better and less disruptive framework compared to other instances. The unintended consequences in most cases were misjudged: policy implementation mostly started off with limited expropriation without compensation but was later expanded to include a broader spectrum of businesses that were considered 'saboteurs' or 'wreckers' of the policy, especially if expropriation did not result in the intended outcomes. In severe cases, 'enemies of the people', which often supposedly included opposition political parties or ethnic minorities, were blamed for policy failure and were targeted under the expropriation without compensation policy, while large-scale famine and full-scale slaughter of livestock also occurred (examples are China in 1958-62, Ukraine in 1928-33, Kazakhstan in 1931-33, Venezuela in 2001-18, and Zimbabwe 2000-18). Corruption escalated and, in instances such as Venezuela and Zimbabwe, resulted in a 'mafia' state, and a breakdown of supply chains. We find it highly unlikely that the first round of expropriation of land without compensation in South Africa will be massively economic disruptive, but the long-term consequences could prove more problematic. The draft of the revised expropriation bill released in December 2018 outlines the procedures for expropriation with and without compensation. The draft document specifies procedures for bonded entities and goes further to list five kinds of property that could be expropriated without compensation. These comprise abandoned buildings (of which many abandoned office blocks are available in South African city centers, such as in Johannesburg and Pretoria), state-owned land (such as that owned by Eskom and Transnet), property in which the state has already invested more than its current market value (allowing for the expropriation of failed government land reform projects), land held for speculative reasons, and farms with labor tenants, where the draft bill makes provision for partial expropriation.

Although the short-term consequences of the expropriation law could be limited, managing expectations of the general population, slow implementation of the proposed policies, or any radical shift towards populism by the ruling African National Congress (ANC) party in the wake of a possible loss of party support could result in more disruptive economic consequences in the long term. More aggressive farmland expropriation could be pursued to pacify the electorate, followed by the possible specific targeting of companies and other properties, ultimately lowering the country's long-term GDP growth potential to 0.5-1.0%. Only under the unlikely long-term assumption of total farmland nationalization would IHS Markit consider South Africa's expropriation path to develop in a similar way to that of Venezuela or Zimbabwe.

The planned amendment of the South African constitution to allow the expropriation of land without compensation will, however, most likely be strongly contested by opposition political parties and civil society groups in the South African economy, which could result in long drawn-out court cases in the next three to five years. Policy uncertainty will, therefore, prevail during this period, limiting the contribution of fixed investment spending towards overall GDP growth.

The ANC development policy scope could in the future also be broadened to target South Africa's savings pool. Assigning prescribed asset allocation for pension funds towards infrastructure, housing, and employment creation has been proposed by the ANC in its 2019 election manifesto, which allows for the forced redistribution and channeling of savings towards the financing of state development projects. However, financing of state-driven large-scale projects, such as Eskom's 4,764-MW Medupi and 4,800-MW Kusile coal-fired power stations, has already been partly financed through South Africa's mature capital markets, ensuring private-sector capital mobilization towards bankable projects in the economy. Forcing asset allocation towards less-feasible state-driven projects will result in capital misallocation and lower returns on investment in a contentious business environment marred by 'red tape'. The Medupi and Kusile projects have been marred by project delays and massive cost overruns, contributing to the current dire situation of the state-owned entity, which increasingly finds it difficult to service its ballooning debt obligations. Finding "bankable" state-driven projects could prove challenging and costly, while tricky policy compliance will overrule project feasibility. All this bodes less optimistically for South Africa's long-term potential growth as productivity drops.

In the near term, South Africa's GDP growth is expected to average 1.4% in 2019, but the risks of even more benign growth over the longer term have increased.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolicies-of-expropriation-and-prescribed-assets-in-south-africa.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolicies-of-expropriation-and-prescribed-assets-in-south-africa.html&text=Policies+of+expropriation+and+prescribed+assets+in+South+Africa+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolicies-of-expropriation-and-prescribed-assets-in-south-africa.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Policies of expropriation and prescribed assets in South Africa | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolicies-of-expropriation-and-prescribed-assets-in-south-africa.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Policies+of+expropriation+and+prescribed+assets+in+South+Africa+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpolicies-of-expropriation-and-prescribed-assets-in-south-africa.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}