Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Dec 20, 2018

Kosovo steps up its struggle for international recognition

- The Kosovo government took the decision to eliminate goods imports from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, on 6 November unilaterally imposing 10% tariffs and increasing them to 100% two weeks later.

- The primary motive behind the move, which breaches Kosovo's obligations under the regional Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) and Stabilization and Association Agreement (SAA) with the EU, is political rather than economic.

- The tariffs represent an attempt by the Kosovo government to puts its political grievances on the international agenda, including greater recognition for its statehood. This latest escalation increases the scope for broader miscalculation by either of the sides.

The immediate trigger for imposing the tariffs was Kosovo's third unsuccessful bid to join Interpol, for which the government blames on lobbying by Serbian officials. To remove the tariffs, the Kosovo government demands full recognition of Kosovo's independent statehood by Serbia and Bosnia, which is highly unlikely. In fact, Kosovo is seeking to convert an implicit recognition, granted by virtue of being in a regional free trade area with both, into an explicit one. The tariffs are a breach of Kosovo's obligations under both the Stabilization and Association Agreement (SAA) with the EU and CEFTA. Nevertheless, by obstructing its membership in international organizations, the Kosovo government regards Serbia to be in breach of its obligations under the Berlin process, a diplomatic initiative by several EU member states aimed at pulling Western Balkans closer into the EU orbit, as well as other agreements. Moreover, Kosovo has for years complained about alleged unfair trade practices by Serbia, such as dumping and non-tariff barriers, which it regards as not sufficiently covered by CEFTA.

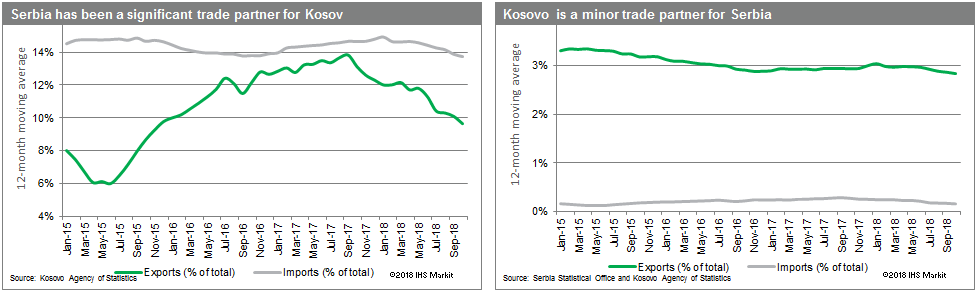

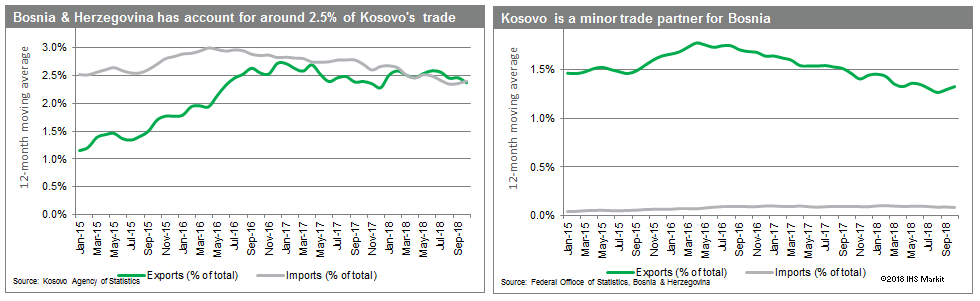

For Kosovo, import substitution is not a credible strategy, given the economy's weak production profile and Serbia's status as the region's industrial base. Indeed, based on bilateral trade data, it is clear that Kosovo is far more dependent on trade with Serbia, which has accounted for 10% of its exports and 14% of imports in first ten months of 2018, even if the relative weight of exports and imports has dipped slightly compared to 2017. For Serbia, exports to Kosovo hover around 3% of total, while imports are a negligible 0.2%. This suggests that the brunt of the economic costs from the tariffs will be borne by Kosovo in the form of higher prices or shortages. The costs could be greater if Serbia and Bosnia impose retaliatory tariffs, which the governments so far ruled out, or increase regulatory barriers on imports from Kosovo.

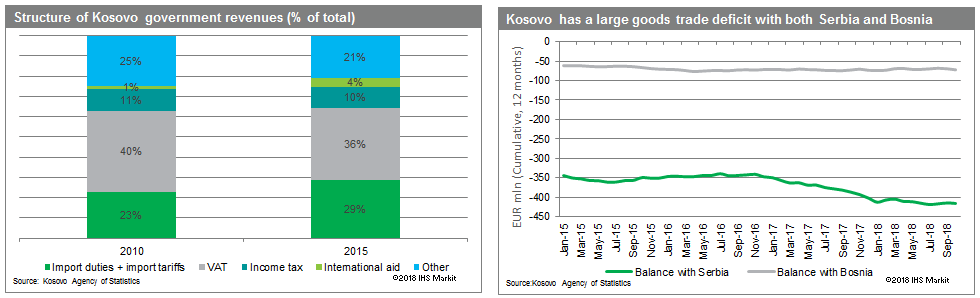

The initial tariff, set at 10%, may have provided a boost for Kosovo government's state budget, especially given its growing reliance on import duties and tariffs over time, while curbing significant trade deficits. However, the 100% tariff will eliminate formal imports from Serbia and Bosnia as exporters will be priced out of the Kosovo market. The largest beneficiaries will likely be other CEFTA members, Albania and Macedonia in particular, due to their geographical proximity and direct competition with Serbian and Bosnian exporters across a range of industries. Another likely side-effect will be the growth in the shadow economy, potentially exasperating Kosovo's problems with combatting organized crime, including smuggling. CEFTA governments aligning themselves to either of the sides could have severe consequences for regional trade and integration.

Ultimately, it remains to be seen whether Kosovo government's tariffs will backfire. Serbia imposed a ban on imports from Kosovo that lasted three years when Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008 and has been sabotaging Kosovo's prospects in various ways. The EU foreign policy chief, Frederica Mogherini, key EU governments, and Washington have all condemned the measure and called on Kosovo to revoke the tariffs. While the recent flare-up in tensions is a major setback for the EU-led efforts to normalize relations, the Serb and Bosnian governments may have won sympathy for not reciprocating with their own tariffs, thus avoiding further escalating the situation.

There is no apparent way out of the current impasse, as both sides are digging in their heels. Due to its precarious position at home and strong rhetoric, Kosovo's government is not likely to back off without what it perceives as significant concessions. It rejected a proposed solution by the EU to replace UNMIK (United Nations Mission in Kosovo) by Kosovo as the signatory to CEFTA. Serbia and Bosnia have refused to negotiate until the tariffs are withdrawn, and even then are unlikely to seriously address Kosovo's grievances. Moreover, in December 2018, the Kosovo parliament voted to establish its own armed forces as a symbol of independent statehood, prompting Serbia to call an emergency UN Security Council meeting. With all this is happening in the context of planning for a controversial land-swap between Kosovo and Serbia, what started out as a politically-charged trade dispute may have increased scope for broader miscalculation.

This blog was written by Daniel Kral, an economics analyst at IHS Markit

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fkosovo-steps-up-its-struggle-for-international-recognition.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fkosovo-steps-up-its-struggle-for-international-recognition.html&text=Kosovo+steps+up+its+struggle+for+international+recognition+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fkosovo-steps-up-its-struggle-for-international-recognition.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Kosovo steps up its struggle for international recognition | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fkosovo-steps-up-its-struggle-for-international-recognition.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Kosovo+steps+up+its+struggle+for+international+recognition+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fkosovo-steps-up-its-struggle-for-international-recognition.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}