Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Oct 10, 2017

Islamic State in decline

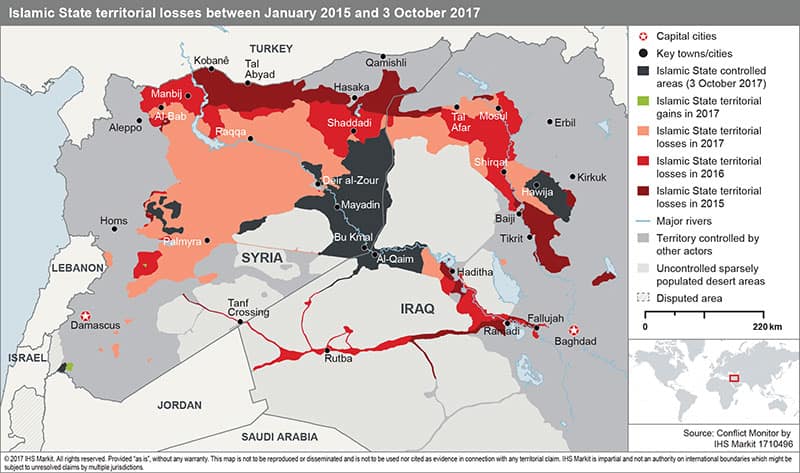

The Islamic State's territorial control in Iraq and Syria will probably come to an end in the coming months, accelerating its transition from a pseudo-state to an underground armed insurgency. According to analysis by IHS Markit’s Conflict Monitor team, territory controlled by the Islamic State has shrunk by 60% between January and October 2017, and the remaining ‘Caliphate’ is just a quarter the size it was in early 2015. The group’s estimated revenues have also dropped by 80% since 2015. It will most likely lose control of the cities of Raqqa and Deir al-Zour in 2017, and what remains of its governance project will cease to exist by mid-2018.

Remnants of the Islamic State will focus its attacks in Iraq on undermining security and central governance and exacerbating social fault-lines with the aim of preparing the ground for future territorial control. It will seek to maintain some semblance of its former governance structure as a shadow state, carrying out summary justice through abductions and executions and portraying itself as exercising power in areas under government control. Loss of territorial control in Iraq is unlikely to significantly diminish its capacity to detonate multiple co-ordinated improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and large-scale vehicle-borne IEDs, and mount complex assaults on urban targets across north Iraq, Kirkuk, and Baghdad provinces.

The Islamic State’s media strategy will continue to promote and exploit sectarian divisions. In Iraq, the group will continue to seek to drive a wedge between the government and Sunni communities, using the capture of Fallujah, Mosul, Ramadi, and Tal Afar by Iraqi armed forces – composed in large part of Shia Muslim Hashd al-Shaabi, or popular mobilisation units (PMUs) – to rally support. Such messaging will resonate within significant segments of the local populations, who have been subjected to well-documented atrocities. This will translate into local support and sympathy for the Islamic State or other Sunni jihadist groups, providing them with safe-houses and areas to organise and stage attacks. It will also remain a rallying point for sympathisers abroad.

The Islamic State will probably shift resources to directly conduct, and indirectly sponsor, assaults in Europe in the 12-month outlook. Within the communities associated with them, there will be individuals who will present long-term challenges of radicalisation and support to a new generation of militant Islamists. The rise of the Islamic State motivated around 5,000 European nationals to join the conflicts in Syria and Iraq. In many cases, spouses and children immigrated to the group’s territories alongside the men. Returning militants are highly likely to seek to join existing militant networks to stage more capable domestic attacks. Their radicalisation attempts will probably support jihadist recruitment for years to come.

With the return of Arab foreign fighters, new jihadist groups are likely to emerge across the MENA region, replenishing the ranks of Islamic State-affiliated groups. Countries at highest risk are those with significant numbers of militants fighting abroad, such as Jordan, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia, and those where the Islamic State is actively attempting to insert itself or re-emerge, such as in Egypt, Libya, Mali, Somalia, and Yemen. Barring an ideological rapprochement, Al-Qaeda will attempt to exploit the Islamic State’s decline in Iraq to its advantage, and attempt to revive its insurgency there by reactivating its old networks and incorporating disaffected Islamic State militants.

Indicators of changing risk environment

Increased risk

- Foreign fighters escape into Idlib province and from there via Turkey to Libya and other safe havens.

- Islamic State-affiliate use of specialised weapons and assault tactics including use of weaponised unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and chemical weapons outside Iraq and Syria, indicating successful and continued skill transfer to other theatres.

- The US Coalition announces a full withdrawal from Syria following the defeat of the Islamic State as a territorial entity.

- Al-Qaeda-associated groups in western Syria accept large numbers of Islamic State defectors into their ranks.

- Al-Qaeda establishes a new official affiliate in Iraq and attracts disaffected Islamic State militants.

- The Islamic State and Al-Qaeda reach a full ideological rapprochement and merge their forces or increasingly conduct joint operations.

- Al-Qaeda veterans in Syria build closer relationships and improve their co-ordination with Idlib-based jihadist groups, indicating a greater potential to secure supply lines to Turkish and potentially, Iraqi territory.

- A coalition loyal to Iran dominates Iraqi security forces and sidelines the US-sponsored elite Counter Terrorism Service, indicating a greater potential to damage the federal government’s communal relations with the Sunni population.

Reduced risk

- Local tribal elements of the Islamic State in Syria turn against foreign fighters.

- The Islamic State’s core leadership in Syria is eradicated before key figures manage to escape to other countries.

- Iraqi tribes reach an accommodation with the Shia-dominated Baghdad government, granting them patronage and employment.

Columb Strack, Senior Middle East Analyst at IHS Markit

Posted 10 October 2017

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-in-decline.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-in-decline.html&text=Islamic+State+in+decline","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-in-decline.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Islamic State in decline&body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-in-decline.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Islamic+State+in+decline http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-in-decline.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}