Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Feb 07, 2018

Islamic State foreign fighters

On 31 January, the UK newspaper The Guardian exclusively reported that Interpol had circulated a list of 50 Tunisian suspected Islamic State foreign fighters who had arrived recently in Italy, some of whom may be intending to travel on to other European countries.

- Islamist militants intent on engaging in terrorist activity are likely to seek to enter Europe without being detected via late-night boat landings in remote areas, or by taking convoluted routes, and changing their identity on the way.

- Networks including foreign fighters are likely to attempt sophisticated, multi-site attacks against shopping malls, transport hubs such as main train stations or airports, or major events taking place at large arenas, stadiums, or concert halls. The likelihood of VBIEDs being successfully deployed would also increase.

- Heightened short-term risk of impromptu low-capability attacks on Italian soil following Interpol’s identification of suspects.

Suspected Islamic State fighters are thought to have arrived on small vessels, on a beach near Agrigento in Sicily. The Interpol list of suspects was originally sent to Italy’s interior ministry, after which it was distributed to European national counterterrorism-terrorism (CT) agencies. Patrolling the entirety of Sicily’s southern coast has proved problematic, with late-night migrant arrivals on beaches near Agrigento particularly prevalent and hard to prevent. This is the most likely route taken by the suspected militants travelling via North Africa.

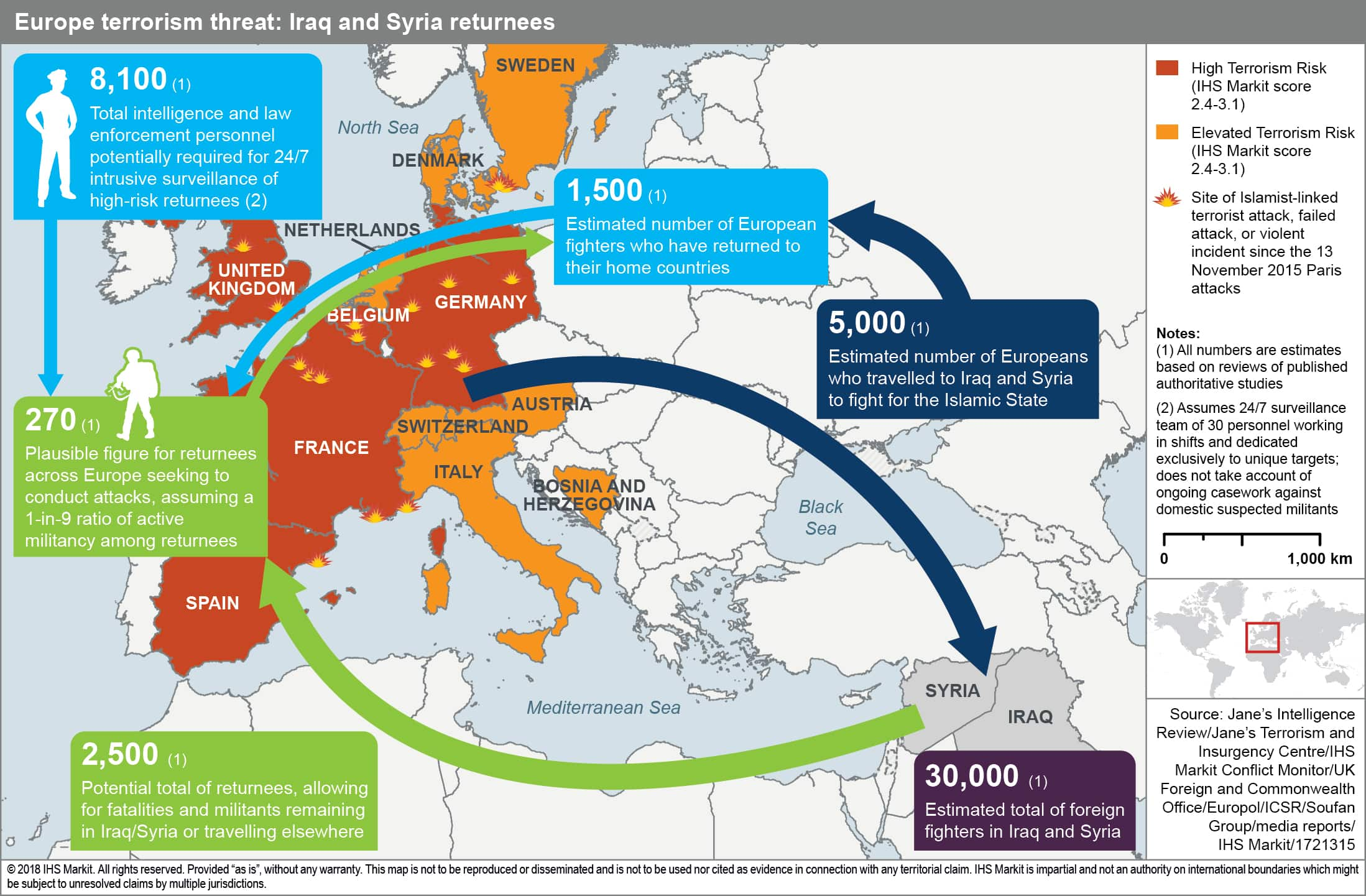

Post-caliphate terrorism threats

The collapse of the Islamic State governance project in Iraq and Syria means that a large number of European and non-European foreign fighters are likely to enter Europe’s southern borders, potentially undetected. More than 5,000 European nationals have travelled to fight for Islamist groups in Syria and Iraq, of whom only approximately 30% are so far known to have returned. Islamist militants intent on engaging in terrorist activity are likely to seek to return without being detected via late-night landings in remote areas, or by taking convoluted routes, and changing their identity on the way. Another potential method involves masquerading as refugees, although the improvement of screening procedures at the European Union’s external borders since 2016, following the refugee crisis, reduces the likelihood that militants would attempt to arrive using this tactic because of the complexity of deceiving authorities with cover stories. Once inside the Schengen passport-free area, crossing borders in continental Europe would be a simple affair. Crossing the UK border undetected, on the other hand, would likely prove extremely difficult, minimising the likely impact on the United Kingdom from returnees seeking to go unnoticed.

Outlook and implications

Islamic State fighters returning with the express purpose of carrying out attacks would likely seek to embed themselves in existing Islamist militant networks across Europe. These are likely to be individuals primed for European attacks, with specific skillsets developed either through battleground experience or by receiving training geared towards the preparation of operations abroad. These militants would substantially increase the capability of European cells, injecting a high level of planning and operational expertise. They would also likely be capable of transferring knowledge on matters such as security awareness, or the construction of reliable improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Networks including foreign fighters would therefore likely be intent on staging sophisticated, multi-site attacks such as those witnessed in Paris in November 2015 and Brussels in March 2016. Both of those attacks involved militants who had received training abroad. France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany are at highest risk of attacks, owing to their active role in fighting the Islamic State and because of the presence of large Muslim communities in which militants have a better chance of blending. However, the preponderance of Islamist networks in these countries would be the main driver behind their prioritisation. Top targets would include shopping malls, transport hubs such as main train stations or airports, or major events taking place at large arenas, stadiums, or concert halls. Reports of counter-terrorism raids uncovering large quantities of stable explosives, assembled with a high level of skill, would be a potential indicator of returnees planning attacks on a larger scale than those seen in recent years, potentially involving vehicle-borne IEDs (VBIEDs), in combination with other forms of weaponry, such as military-grade firearms. Italy is less at risk than the aforementioned countries because of the lower prevalence of Islamist networks in which returnees could embed themselves. Nevertheless, there is a heightened short-term risk of the 50 estimated Tunisian nationals carrying out impromptu low-capability attacks on Italian soil following their identification by Interpol that could scupper their plans of travelling across borders.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-foreign-fighters.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-foreign-fighters.html&text=Islamic+State+foreign+fighters","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-foreign-fighters.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Islamic State foreign fighters&body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-foreign-fighters.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Islamic+State+foreign+fighters http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fislamic-state-foreign-fighters.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}