Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Feb 15, 2018

India Naxalite update

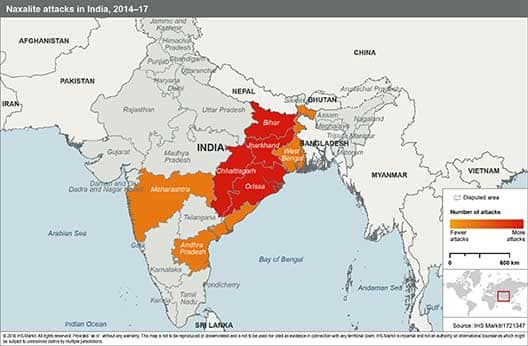

The number of states affected by significant Naxalite activity has been reduced from seven in 2011 to five as of 2017.

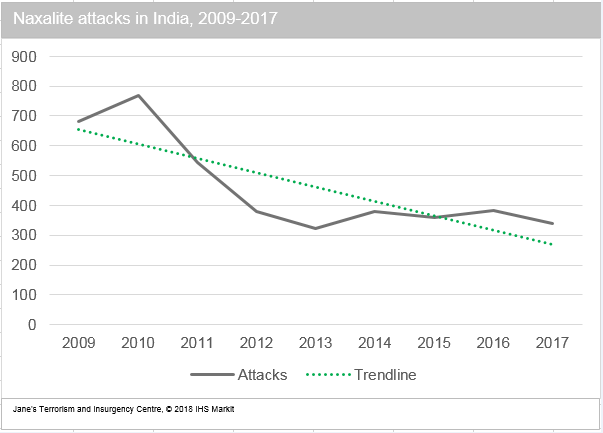

- Attacks by Naxalite militants have significantly reduced in India from about 768 in 2010 to 340 in 2017.

- More than half of attacks were aimed at security forces and government assets, and approximately 18% targeted industrial assets such as mining, construction, and cargo.

- In late 2017, Nambala Keshav Rao (alias Basavraj), the military commander of the foremost Naxalite group – the Communist Party of India (Maoist) – was promoted as the group's leader.

- Rao's promotion implies a branching-out of Naxalite leadership, increasing the likelihood of a prolonged conflict.

Marked fall in activity

According to Jane's Terrorism and Insurgency Centre (JTIC) there were 768 Naxalite (Maoist militants) attacks in 2010, falling to between 340 and 380 from 2014–2017. The area affected by Naxalite activity has also shrunk: according to the Ministry of Home Affairs, in 2011 seven Indian states reported significant Naxalite activity compared with five in 2017 (Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, and Odisha); Naxalite activity has been virtually eliminated from Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal. For the third consecutive year, the majority of attacks were recorded in the thickly forested state of Chhattisgarh, followed by Jharkhand.

Security forces remain at greater risk than industrial assets

JTIC data suggest that more than half of Naxalite attacks across all states between 2014 and 2017 targeted state assets – such as security forces, government offices, road and railway infrastructure, mobile-phone towers, and power stations – compared with 18% against industrial assets, primarily mining- and construction-related materials and cargo. Naxalites usually attack road assets when construction is under way, and target rail assets by uprooting railway tracks with tools like crowbars or shutting down railway stations by holding officials hostage at gunpoint. These attacks are aimed at disrupting the government's development programme.

Attacks against industrial assets involve Naxalites capturing mining or construction assets, or holding employees of private companies hostage. Unlike with state assets, these attacks are not aimed at destroying assets but at leveraging them for financial bargaining with proprietor companies. Naxalites are known to use this source of funding for acquiring arms and to undertake recruitment. The militants usually destroy such cargo in the event that companies refuse to adhere to their extortion demands.

Government is resolute, but Naxalites have adopted new leadership

The reduction in Naxalite activity is mainly attributable to Operation Green Hunt, which was launched in 2009 and is undertaken jointly by the security forces of the central and state governments to eliminate Naxalites. The Ministry of Home Affairs reported that 222 Naxal fighters were killed by security forces in 2016, up from 89 in 2015.

Furthermore, Naxalites have been unable to improve their capabilities. Although groups in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand have access to landmines, their tactics mostly remain ambushes with small-arms and crude improvised explosive devices. They are also known to conduct arson attacks against stationary vehicles, particularly targeting trucks carrying cargo.

In a significant development, an IHS Markit source has confirmed that two changes in Naxalite leadership took place in 2017. Since 2004, the movement was led by Ganapathy, the general secretary of the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-M). Owing to his poor health and intense search operations to arrest him, the movement is now reportedly being led by Nambala Keshav Rao (alias Basavraj), the CPI-M's military commander, as of late 2017. Rao is generally noted as an explosives expert and as the group's main procurer of arms.

Furthermore, Madvi Hidma, a Naxalite battalion leader in Chhattisgarh, was reportedly included in the CPI-M's Central Committee in September 2017; this marked only the second time that a member of a lower-caste tribal community had been included, and was probably intended to address the Naxalites' alleged weakness of being perceived as a pro-lower-caste movement that is generally led by upper-caste Hindus.

Outlook and implications

Despite the changes in leadership, the extensive security presence during the 2018–19 election years is likely to deter significant Naxalite attacks. With state assembly elections scheduled in Chhattisgarh for the fourth quarter of 2018, and a general election scheduled for the first quarter of 2019 (and potentially earlier), state and central governments are highly likely to deploy additional security forces in anticipation of attacks. Approximately 70 central force battalions (about 70,000 personnel) have reportedly been deployed in Chhattisgarh alone.

Following the elections – when the security presence is likely to be reduced – a minimal increase in attacks is likely, but is unlikely to exceed the levels recorded to date. The risk to industry assets remains moderate, with attacks likely to be undertaken for the purpose of extortion. Basavraj's promotion implies a branching-out of Naxalite leadership, rendering the group less likely to observe a further reduction in attacks. The authorities have to date focused on eliminating a single top leader (Ganapathy); however, under new leadership the movement is likely to prove more sustainable. Hidma's promotion increases the likelihood of a stronger recruitment drive among lower-caste tribal communities, focused in Chhattisgarh. Geographically, a resurgence in Naxalite activity in Madhya Pradesh is likely; government intelligence indicates that the Naxalite arms-training camp has probably been shifted from Bastar in Chhattisgarh to Balaghat in Madhya Pradesh.

Currently, joint operations by central and state-level security forces that are under way in affected states are generally hindered by poor co-ordination. The effectiveness of such counter-insurgency efforts is likely to improve if state-led elite forces are established specific to each affected state: for example, elite forces created by officers of the Indian Police Service of Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal have been pivotal in virtually eliminating Naxalite activity.

Conversely, the number of attacks is likely to increase if Naxalites appoint a larger proportion of lower-caste members from tribal communities to positions of leadership in states beyond Chhattisgarh. In addition to stronger recruitment, such a strategy would also be likely to establish a support base among members of tribal communities on grounds of a common identity.

Deepa Kumar, ECR Analyst at IHS Markit

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-naxalite-update.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-naxalite-update.html&text=India+Naxalite+update","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-naxalite-update.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=India Naxalite update&body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-naxalite-update.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=India+Naxalite+update http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-naxalite-update.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}