Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

May 21, 2018

Eurozone slowdown: What’s going on

- The deterioration in some economic indicators in the early part of the year has been exaggerated by various transitory factors, including adverse weather.

- There is no fundamental reason for a sudden slump. But a moderation in underlying growth momentum was likely from last year's elevated levels.

- Heightened uncertainty could hold back expenditure, especially investment, while rising oil prices are crimping household real incomes.

Many forecasters were caught on the hop last year by the unexpected vigor of the Eurozone economy. Prior disappointments and political clouds obscured numerous reasons to be cheerful. Growth expectations were belatedly adjusted upwards, only to be followed by a sharper than expected slowdown in the early months of 2018. How concerned should we be?

Disappointing data

The stand-out feature of the data early this year was the deterioration in the industrial sector. Production contracted on a m/m basis in each of the three months to February, the first such run since the tail-end of the Eurozone crisis in 2012. This contributed to real GDP expanding at its slowest rate for six quarters in Q1: the 0.4% q/q rise was well down on 2017's 0.7% q/q average. Still, from such dizzy heights, a growth moderation was inevitable.

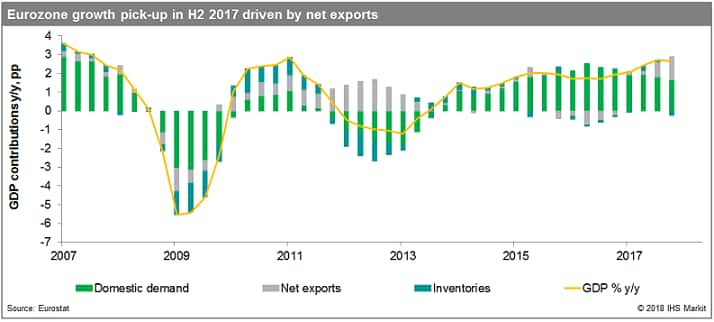

On occasion, the impact of a contraction in the industrial sector can be outweighed by buoyancy in other areas. Not this time. Retail sales declined in Q1 for the first time in nine quarters, as did construction output. Trade data also suggest a reduced contribution to growth from net exports (around ½ a percentage point on average in H2 2017). This is particularly relevant as a pick-up in net trade drove the Eurozone's growth spurt last year (see chart).

Headwinds blowing

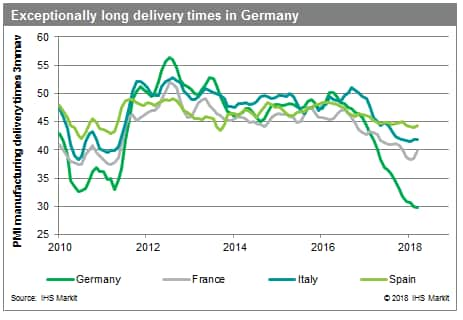

The lagged effects of exchange rate appreciation, global growth and trade passing their peak (evident in our PMI data, both for advanced and emerging economies) and capacity constraints in some parts of the Eurozone are all contributing to a slowdown. On the latter, suppliers' delivery times in our manufacturing PMI for Germany have reached unprecedented lengths.

Noise or signal?

The disruption caused by various transitory factors have led the data in some areas to paint a misleadingly poor picture of Eurozone economic conditions. These include adverse weather, the timing of Easter and country-specific issues like French strike action and an outbreak of flu in Germany. Indeed, industrial output rebounded in March.

We see little fundamental reason why the economy should suddenly fall off a cliff. Policy conditions, both monetary and fiscal, remain supportive. Indeed, the ECB's latest bank lending survey showed a further easing of credit conditions across all types of loan. The cost of credit is also exceptionally low, including in the Eurozone's periphery. As for external demand, momentum should remain supportive, helped by expansionary US fiscal policy.

Rising uncertainty

That said, we are cognizant of downside risks. Protectionism is a prominent source of concern, plus the threat of sanctions following the change of US policy on Iran. While not the most likely outcome, the threat of an all-out trade war could be enough to defer expenditure, especially investment. Post-crises, it took a long time to get the Eurozone investment cycle going and it might be vulnerable to a sudden stop should uncertainty continue to increase.

Recent political developments in Italy, and the impact on sovereign yields and spreads, also merit attention. The inability to form a government is usually the problem, not the other way around. But judging by the content of the proposed policy agenda, a Lega-M5S tie-up would inflame tensions with the EU and other member states.

Higher oil prices are also a growth constraint. Low commodity prices and inflation were a key contributor to the pick-up in household real incomes which underpinned the solid (if unspectacular) growth in Eurozone consumer spending since 2015.

Potential growth in perspective

Eurozone growth rates also need to be put in context. The business cycle is less advanced than the US but the economy cannot grow at a rate far in excess of potential indefinitely. We have some sympathy with the view emanating from the ECB recently that "reverse hysteresis" effects could generate higher potential growth in the Eurozone. However, given numerous structural impediments, it is unlikely to be significantly north of 1½% in real terms, absent an acceleration in supply-side reforms (which the political climate in many countries makes highly unlikely).

The bottom line?

Some recent data paint a misleadingly downbeat picture of economic conditions. But a moderation in growth is already under way and we need to monitor closely the potential impact of heightened uncertainty across a range of areas.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-slowdown-whats-going-on.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-slowdown-whats-going-on.html&text=Eurozone+slowdown%3a+What%e2%80%99s+going+on+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-slowdown-whats-going-on.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Eurozone slowdown: What’s going on | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-slowdown-whats-going-on.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Eurozone+slowdown%3a+What%e2%80%99s+going+on+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-slowdown-whats-going-on.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}