Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jul 12, 2018

E-commerce retail sales tax

On 21 June, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in the case of South Dakota v. Wayfair that state legislatures could require out-of-state retailers to remit sales taxes from online purchases made by state residents. This reverses the 26-year precedent that exempted retailers from collecting sales taxes on purchases if the seller did not have a physical presence in the state. Up to this point, online retailers were not required to charge consumers a sales tax on remote (out-of-state) sales, unless that retailer had a physical presence in the state in which the buyer was located. This precedent-which was upheld in a 1992 Supreme Court ruling in Quill v. North Dakota-has caused state and local governments to argue that they were unfairly losing out on sales tax revenues. Similarly, brick-and-mortar retailers have argued they are at a disadvantage and that their online competition is receiving an unfair tax break. The commerce clause in the US Constitution leaves the door open for Congress to change the "physical presence" requirement, but no federal mandate on taxation of remote sales has been written into law. After numerous lawsuits, years of lobbying, and work-arounds by state legislatures, the question was put before the Supreme Court, which gave states the go-ahead to tax online sales the same as traditional retail sales.

It is a common misconception that all internet sales were not being taxed prior to the Supreme Court case. In fact, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimates that 80% of the potential revenue from requiring all internet retailers to levy taxes was already being collected as of 2017. One reason for this is that the "physical presence" requirement means that large online retailers with as little as a few customer service representatives or a single warehouse in a state still must collect a sales tax for orders from that state. Given how widespread the distribution networks have become, the largest online retailers have a presence in most of the states that collect sales taxes, and thus are already complying as if they were brick-and-mortar retailers.

Caveats come into play when dealing with taxation on third-party sales on marketplaces such as eBay, Amazon Marketplace, or Etsy. Because marketplaces are simply a forum for third-party sellers to leverage larger companies' established marketing and distribution operations, it is a gray area as to whether the onus should be on the marketplace owner or the third party to collect taxes on these purchases. The GAO estimates that, at most, one-third of these marketplace transactions currently includes sales taxes. Given that these types of sales are estimated to account for over $200 billion of Amazon's worldwide transactions, the potential benefits to state governments are nontrivial. As such, a growing number of states have mobilized over the past decade by legislating various "Amazon Laws," the colloquial term for state-level laws that seek to broaden the "physical presence" requirement. For example, several states have passed legislation that requires e-marketplaces to collect taxes on behalf of third-party sellers who are using marketplace services such as click-through marketing or order fulfilment to ship out of state. The "Amazon Laws" have had varying degrees of success in terms of compliance and legality, so state governments have been waiting for greater clarity on a federal level. In response to this Supreme Court ruling, many states will accelerate efforts to mimic the South Dakota law that was upheld. These types of laws have broad bipartisan support, so legislation will likely be enacted in most states relatively quickly.

While this ruling is a win for state and local governments, the marginal price increases resulting from higher sales taxes on some orders will not be a major deterrent for online shopping. In the early stages of the e-commerce revolution, large online retailers attracted consumers partially because they could offer lower prices, aided in part by not paying sales taxes. But that tax avoidance advantage has gradually eroded in the last decade, and the largest retailers are already paying near to their share of taxes. A more significant (and perhaps, dominant) reason why consumers increasingly prefer online retail is the convenience factor. Amazon and other companies have introduced technology that allows consumers quick access to nearly all of their household items within days, or even hours, after investing only a few minutes into online shopping. That convenience advantage is not going away and may even have room to grow.

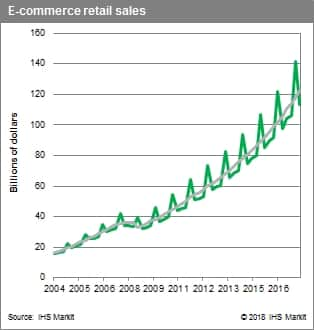

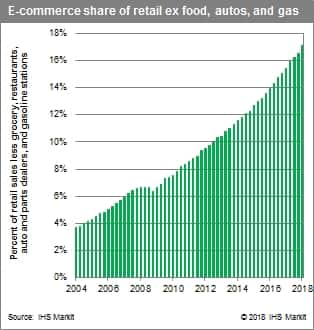

E-commerce retail sales have grown from a $20 billion industry in 2005 to more than $120 billion currently, and that is likely a low estimate since it does not account for brick-and-mortar sales that have adopted mixed-channel sales strategies in recent years. In terms of market share, e-commerce has gained on overall retail sales. Excluding segments with marginal online options such as food services, groceries, auto dealers, and gasoline stations, the market penetration of e-commerce has gone from 4% in 2005 to over 17% this year, and the rate of change has increased in recent years even as the industry has matured. The line between brick-and-mortar and online shopping will continue to blur as more retailers incorporate some form of online presence in their operations.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecommerce-retail-sales-tax.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecommerce-retail-sales-tax.html&text=E-commerce+retail+sales+tax+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecommerce-retail-sales-tax.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=E-commerce retail sales tax | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecommerce-retail-sales-tax.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=E-commerce+retail+sales+tax+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecommerce-retail-sales-tax.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}