Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Dec 17, 2018

Demographics in Baltics make long-term consumer spending prospects bleaker

- Short-to-medium-term prospects for consumption growth remain favourable because of rising wages, record high household deposits, room for higher household borrowing and strong fiscal position.

- Substantial demographic change will be affecting some sectors' growth in particular, as well as total purchasing power and productivity growth. The three countries risk falling into a middle-income trap if reforms in health, education and public sector administration are not successfully implemented.

- Long-term growth prospects will largely be determined how government will be able to address labour market challenges with improvements in population health, educational outcomes and effectiveness of public spending.

Baltic countries can provide a positive surprise in near future

Real disposable income has risen faster than the in EU on average since the crisis, especially in Lithuania and Latvia, while high vacancy rates and a lack of qualified labour force are further pushing up wage growth. Rising wages in private and public sector together with rising social transfer will be the main drivers of consumption growth in near-medium term.

Moreover, rising deposit and cash holding suggest that households can withstand short-term fluctuations in their incomes relatively well. Responsible fiscal policy in recent past means that governments would not be forced to turn to procyclical fiscal policy by raising taxes and decreasing spending during a moderate downturn. This will preserve disposable income in the medium term because it is less likely that social benefits, public-sector wages, and spending on investments will be drastically reduced.

Finally, low indebtedness levels of the Baltic states, especially in Latvia and Lithuania measured as a share of disposable income, suggest that household consumption in the medium term could be supported by higher borrowing.

Demographic trends are working against Baltic countries

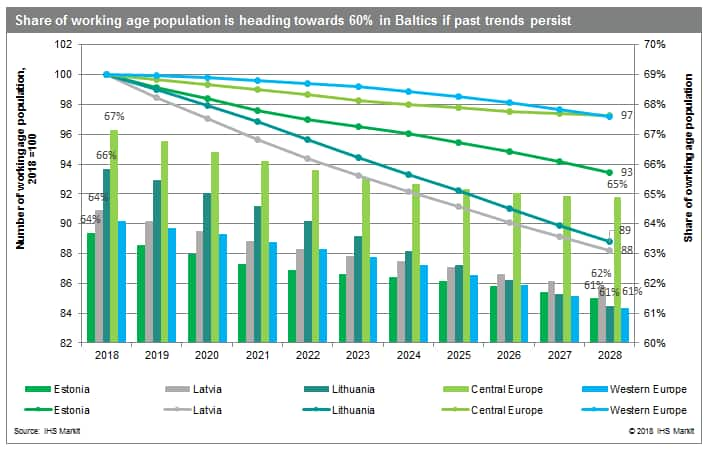

The working-age population in Latvia and Lithuania has been decreasing faster than in anywhere else in the European Union. If these trends continue, Lithuania and Latvia will lose another 10% of their population during the next 10 years and it will shrink, but to a lesser extent in Estonia as well (see the chart below). The working-age population will shrink faster than the total population.

Lack of a qualified labour force to fill new vacancies will likely result in decreasing employment meaning that wages and social benefits will have to grow faster than in the past to sustain the same growth in purchasing power.

The relative number of dependents will rise, straining the incomes of social groups dependent on budgetary transfers and public sector workers. A changing economy and skills mismatch have resulted in higher structural unemployment rates, especially in Latvia and to a lesser extent in Estonia. This means that governments will need additional resources to support this part of the population. Low life expectancy rates and the EU's lowest healthy life expectancy rates for males suggest that a large share of the population might be less productive, unable to work full time or inactive, and dependent on social transfers because of poor health.

Urbanisation and changing age structure will affect consumption patterns

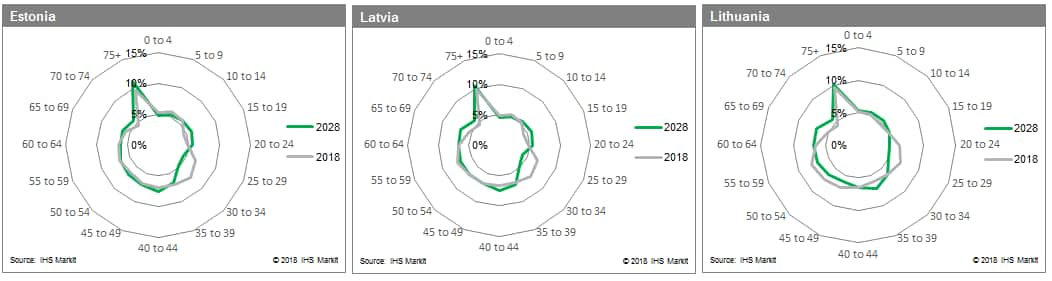

A shrinking share of 20-34-year-olds in the Baltic countries might have a negative effect on demand for housing, and related goods and services. However, a rising proportion of the 35-44-year-old population might mean that consumer markets will benefit from customers with higher purchasing power, as people with more work experience tend to earn higher wages.

However, purchasing power will remain lower in less populated more remote regions, with limited niches for businesses to expand their activities.

Time for unpopular, but necessary, reforms

Emigration might become less of a problem in the future as economic conditions improve. However, decreased share of working age population is working against productivity growth and might limit public budget revenues.

Lower wage levels and geographical location will still enable the countries to attract some foreign investment, but strong recent wage growth suggests that this comparative advantage will further decline in importance. The tax system is favourable to foreign investors, but investments in higher-value-added sectors will require a highly skilled and productive labour force.

Unless reforms in education and the healthcare system are implemented to raise the total-factor productivity of the remaining labour force, there is a high risk of the three countries finding themselves falling into a middle-income trap.

If the Baltic countries want to sustain their favourable taxation environment, they will have to find ways to perform all other functions with fewer resources. Careful evaluation of the value of those functions and e-solutions on the one side and more effective tax administration through a lower shadow economy and review of ineffective tax exemptions on the other side are necessary, but often politically unpopular, measures.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdemographics-baltics-longterm-consumer-spending.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdemographics-baltics-longterm-consumer-spending.html&text=Demographics+in+Baltics+make+long-term+consumer+spending+prospects+bleaker+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdemographics-baltics-longterm-consumer-spending.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Demographics in Baltics make long-term consumer spending prospects bleaker | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdemographics-baltics-longterm-consumer-spending.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Demographics+in+Baltics+make+long-term+consumer+spending+prospects+bleaker+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdemographics-baltics-longterm-consumer-spending.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}