Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Dec 28, 2020

China’s bond defaults

Between October and December 2020, three companies were involved in high-profile, unexpected bond defaults in mainland China: Yongcheng Coal and Electricity, a state-owned energy company that defaulted on a CNY1-billion (USD152.7 million) bond; Tsinghua Unigroup, a computer chip maker majority-owned by Tsinghua University, which defaulted on a CNY1.3-billion bond and a USD450-million bond after failing to roll over its debt; and the owner of Brilliance Auto, state-owned Huachen Automotive Group, which failed to pay a CNY1-billion bond and later entered bankruptcy restructuring.

Mainland China has a history of bond defaults but bank restructuring has indicated wider financial stress.

The recent high-profile defaults by the three SOEs have totaled about CNY6.3 billion so far. This is a small proportion of total corporate bond issuance so far in 2020 (as of the end of November, this is equivalent to 1.7% of CNY363.5 billion), according to IHS Markit's calculations using China Bond data. Moreover, the latest failures are not particularly large when compared with SOEs' previous defaults. In the second half of 2018, five SOEs filed for bankruptcy with total liabilities of CNY9.9 billion, the largest default of which was CNY5.8 billion. The recent events are important considering their impact on the prior perception of implicit guarantees for SOEs, and because they involve enterprises active in areas perceived as strategically key, including computer chips and the automotive sector, rather than involving highly indebted conglomerates or real estate companies. Apart from bond defaults, bank failures also increase investor concerns, with Baoshang Bank, a local bank based in Inner Mongolia, becoming the first commercial lender in mainland China to file for bankruptcy in two decades. Local media reported that in 2020 alone, as of August, there had been more than 20 mergers and reorganizations involving small and medium-sized regional banks seeking to consolidate capital. A move to tighter regulatory scrutiny and efforts to encourage increased investor focus on risk were also flagged by the recent high-profile withdrawal of Ant Group's initial public offering (IPO) in Shanghai and Hong Kong on regulatory grounds after achieving a global record for potential share issuance with massive oversubscription, and also by the withdrawal of a planned blockchain-based bond for China Construction Bank's Malaysian branch.

Mainland China's central government has flagged concerns about the accumulation of debt leading to systematic financial risks, which aims to prepare markets for defaults.

Former finance minister Lou Jiwei highlighted in November that mainland China needs to "investigate an orderly withdrawal from loose monetary policy" because of its debt pressure but fast withdrawal is unlikely to avoid triggering a debt crisis, indicating continued fiscal expansionary policy in 2021 but involving smaller scale adjustments. Vice-Premier Liu He noted that recent increase in default cases was a result of "cyclical, institutional but also behavioral factors", including fraud, false information disclosure, inappropriate transfer of assets, and misappropriation of issue proceeds. Premier Li Keqiang during his meeting with officials from Guangdong, Heilongjiang, Hunan, Yunnan, and Shandong (which, combined, represents around one-quarter of mainland China's economy), had asked the officials to "honestly report the economic situation, plans for the next economic period, and their opinions on mainland China's macroeconomic policies". The PBoC also join this view. PBoC Governor Yi Gang emphasized the issue of insufficient supervision in systemic financial risks and highlighted that local governments and financial institutions have pressured the central government and the PBoC to bear the costs of resolving financial stresses. The article proposed holding financial institutions, local governments, and financial regulatory authorities responsible for future deterioration in financial risks.

Defaults show a delayed response to economic slowdown, while policy measures have delayed corporate failure.

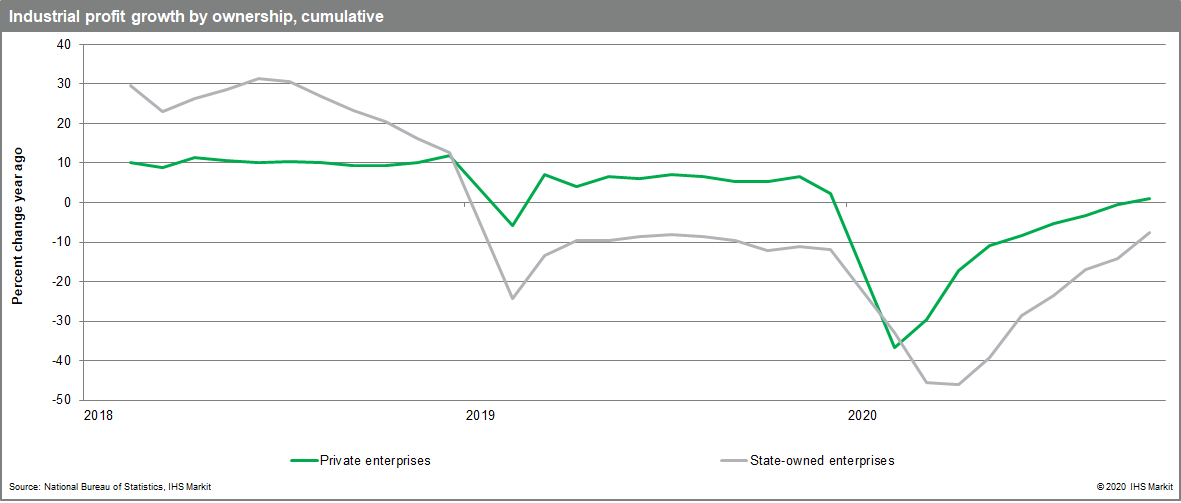

The latest defaults occurred in the third quarter of 2020 after the domestic economy recovered, instead of during the sharp economic recession in the first quarter. They are likely to reflect a lagged reaction to economic slowdown, initially mitigated by policy measures supporting the corporate sector, including easier monetary policy that permitted stressed firms to access external funding at a lower cost. Poor profitability is another factor behind SOEs' defaults. The National Bureau of Statistics has reported that industrial profit growth of SOEs has lagged that of the private sector since the beginning of 2019. The year-to-date industrial profits of the private sector returned to a positive level in October, while that of SOE remained 7.5% down on a year-on-year basis.

Local SOE defaults have wider repercussion for the region.

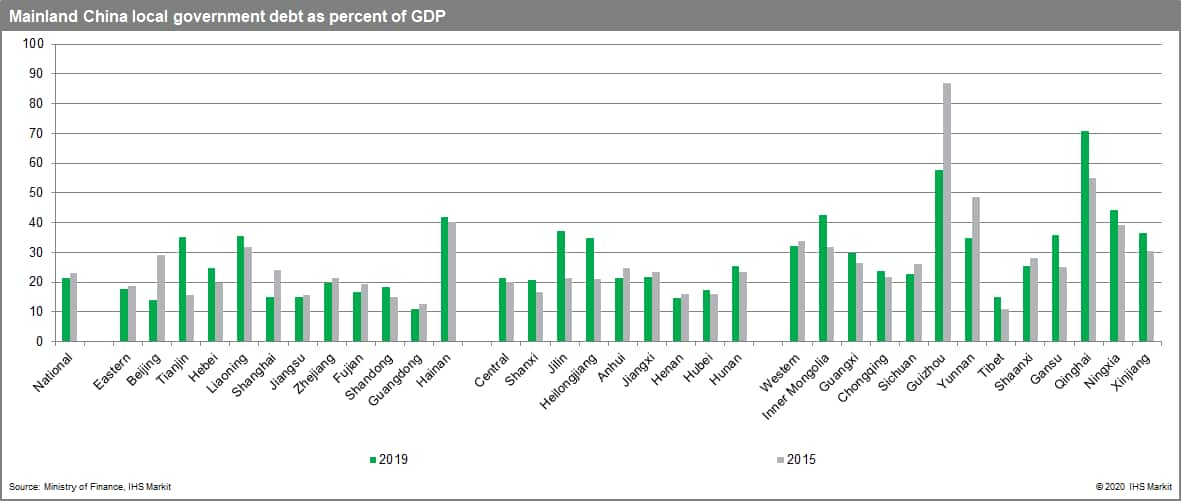

After local SOE Qinghai Yanhu defaulted in 2019, Qinghai province's new total social financing (TSF) declined from CNY128 billion in 2019 to only CNY45 billion through September this year, compared with a 15% increase nationwide during this period. In addition, credit spreads for borrowers in the region rose sharply by 20% after the default, while those on local government financing vehicle bonds rose by over 60%. Moreover, the proportion of loans applying rate above the benchmark loan rate has increased from less than 35% to 60% in Qinghai (guiding the central bank's announced interest rate for commercial bank loans). As a result, the region has become increasingly reliant on government funding, with 80% of its 2020 TSF coming from local authority bonds. The default also impacted on economic growth, prior to the default, Qinghai had been outperforming national level growth. However, after the default in 2019, Qinghai's fixed asset investment dropped significantly, recording a 5.2% year-on-year (y/y) contraction in the first 10 months of 2020, versus 1.8% y/y expansion nationwide. As a result, Qinghai's real GDP growth fell below the national average for most quarters since 2019. All of this didn't improve debt burden, with industrial firms' liability-to-asset ratio in Qinghai rising from 68% at the beginning of 2019 to 73% after the default.

The banking sector's bond investment is a significant portion of banking-sector assets, recent defaults likely pushes some towards lending to MSMEs.

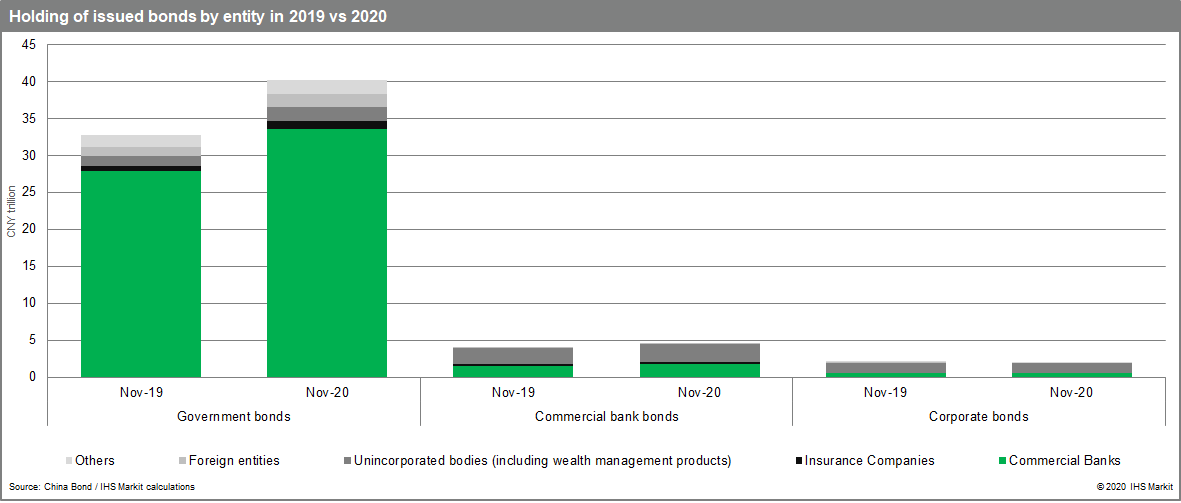

According to IHS Markit's calculations using China Bond and

CBIRC data, banks' investment in bonds accounted for around 19% of

total banking-sector assets in the third quarter of 2020, versus

56% of total banking-sector assets in the form of bank loans. The

latest data show that investment in bonds has risen by 17.1% y/y,

compared with 13.3% in November 2019, and has exceeded the loan

growth rate of around 13% y/y, signaling an increased proportion of

assets being held as bonds. However, most of the growth has

concentrated in government bonds, with investments in corporate

bonds more or less flat between November 2019 and 2020. Although

even before COVID-19, the Chinese authorities have been encouraging

banks to lend more to MSMEs to rebalance the sector's lending away

from housing and traditional corporate lending, the Chinese

authorities have stepped up their efforts to encourage MSME lending

by reducing the loan prime rate and the reserve requirement ratio.

It is likely that some of the funds previously used to purchase

corporate bonds had been diverted to MSME lending, and the recent

bond defaults provide banks with more reason to further increase

lending in this direction. However, despite the fact that lending

to micro and small enterprises has

risen at a faster rate than bond investment in mainland China, at

30% in 2020, lending to MSEs is unlikely to replace bond

investments in the next two years due to outstanding lending to

MSEs stood at over 5% of total assets in the third quarter of 2020,

compared with 19% of total assets for bonds.

Chinese authorities have been working to reduce moral hazard related to investments.

The authorities have previously warned that smaller state-owned banks will be allowed to fail and have demanded that banks do not guarantee the repayment of principal on shadow bank investments for retail customers. The reaction to recent developments - such as approving the bankruptcy of Baoshang Bank - appears consistent with these principles. The domestic reaction - notably the investor "surprise" over SOE failures - highlights that moral hazard and a misconceived perception of implicit state support for SOE debt remain problematic. The worldwide economic impact of COVID-19 provides a useful background to change this view, with the government likely to attribute blame for further state-owned companies' failure on global economic factors; further defaults should give additional encouragement to investors to rethink their strategies.

Wider SOE defaults are likely, with both central and local governments expanding the scope for companies to default without state intervention, affecting both private-sector firms and smaller state-owned companies and financial institutions.

Increasing tolerance for defaults and bankruptcies are consistent with the administration's policy stance under President Xi Jinping's long-term plan to increase the efficiency of state-owned companies, but this is far from new. The 2015 "Guiding Opinions on Deepening the Reform of State-owned Enterprises" highlighted the need for state companies to become "market-driven entities which manage their own profits, losses, and risk-taking behavior". Nevertheless, to avoid major local dislocations or damage to overall economic recovery, the government is, in our view, still highly likely to intervene to support strategically important state-owned companies and prevent defaults that would trigger localized financial stress events. This approach will leave local-level, small-scale state companies with cash flow and financial difficulties less likely to gain local government financial support, particularity for firms not directly controlled by government entities. Additionally, wider defaults in assets previously considered to enjoy state backing is likely to damage investor confidence gradually, in turn making it more difficult for local governments and SOEs to obtain new financing.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fchinas-bond-defaults.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fchinas-bond-defaults.html&text=China%e2%80%99s+bond+defaults+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fchinas-bond-defaults.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=China’s bond defaults | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fchinas-bond-defaults.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=China%e2%80%99s+bond+defaults+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fchinas-bond-defaults.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}