Brazilian presidential race

The latest opinion polls show outsiders Jair Bolsonaro of PSL (extreme-right) and Marina Silva of Rede (centre-left) leading the race for the October presidential election.

- The Workers Party (PT) and its imprisoned leader former President Lula will affect the electoral landscape once they choose their candidate.

- In the meantime, all parties are trying urgently to forge alliances before the official campaign starts in mid-August.

- With dozens of candidates seeking office and the pro-business centre-right still to agree on a unified candidate, the fractured political landscape increases the chances that an outsider from the right or left will secure office.

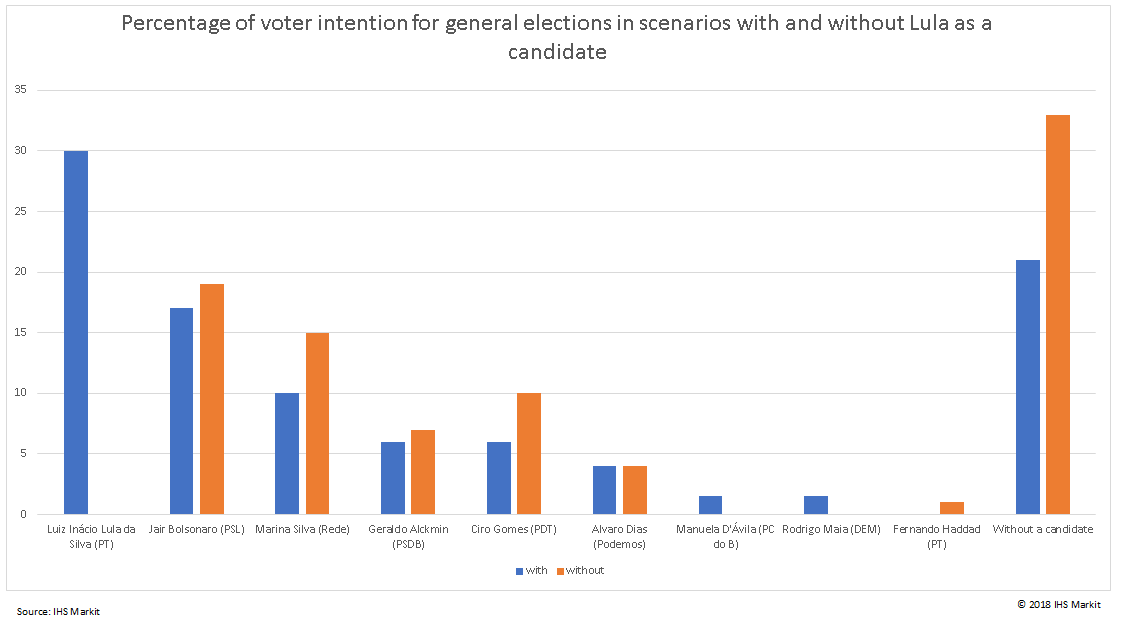

The Brazilian presidential election will take place in less than three months, but its outcome remains highly uncertain. The latest opinion survey by pollsters Ibope and Datafolha, released in late June, show outsiders leading the race. The current voter preference is for extreme right-wing Federal Deputy Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party (PSL, Partido Social Liberal) with some 17-19% of the votes. He is technically level with center-left former environment minister Marina Silva of Rede Sustainability (REDE, Rede Sustentabilidade), who has 13 -15% support. Another outsider from the center-left, former Finance Minister Ciro Gomes, of the Democratic Labor Party (PDT, Partido Democrático Trabalhista), ranks third with 8-10%.

Meanwhile, support for center-right pro-business candidates such as the former Governor of São Paulo, Geraldo Alckmin, of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB, Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira), remains at around 6-7%. Other candidates of the pro-business camp such as the speaker of the Lower House Rodrigo Maia (DEM) and former Finance Minister Henrique Meirelles (MDB) register 1% or less.

The Workers Party (PT) struggling to remain relevant

The Workers Party (PT, Partido dos Trabalhadores), which governed Brazil between 2003 and 2016, is facing a dilemma over who to field while its main leader, former President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, is in prison on corruption charges. Lula's popularity remains high with one-third of voters saying they would vote for him if eligible to stand. On this basis, Lula would defeat any candidate in both rounds of the election. The PT claims that the charges against Lula are politically motivated and are adamant that he is their only candidate. However, Lula's 12-year prison sentence, as ratified by a court of appeal early this year, makes it highly unlikely that the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) would accept the registration of his candidacy. Eventually, the PT will have to choose a different candidate (or remain unrepresented): meanwhile the electoral prospects for the main contenders will remain highly uncertain.

If Lula cannot run, polls indicate that more than 30% of his supporters would back a candidate he indicates. Lula's endorsement would transform the prospects for a left-wing candidate. Of these, Ciro Gomes, who has good rapport with several PT leaders, has some chances of securing Lula's endorsement. Alternatively, the PT could choose its own candidate, potentially the former mayor of São Paulo Fernando Haddad, but his support currently stands at just 2%.

The race to build alliances

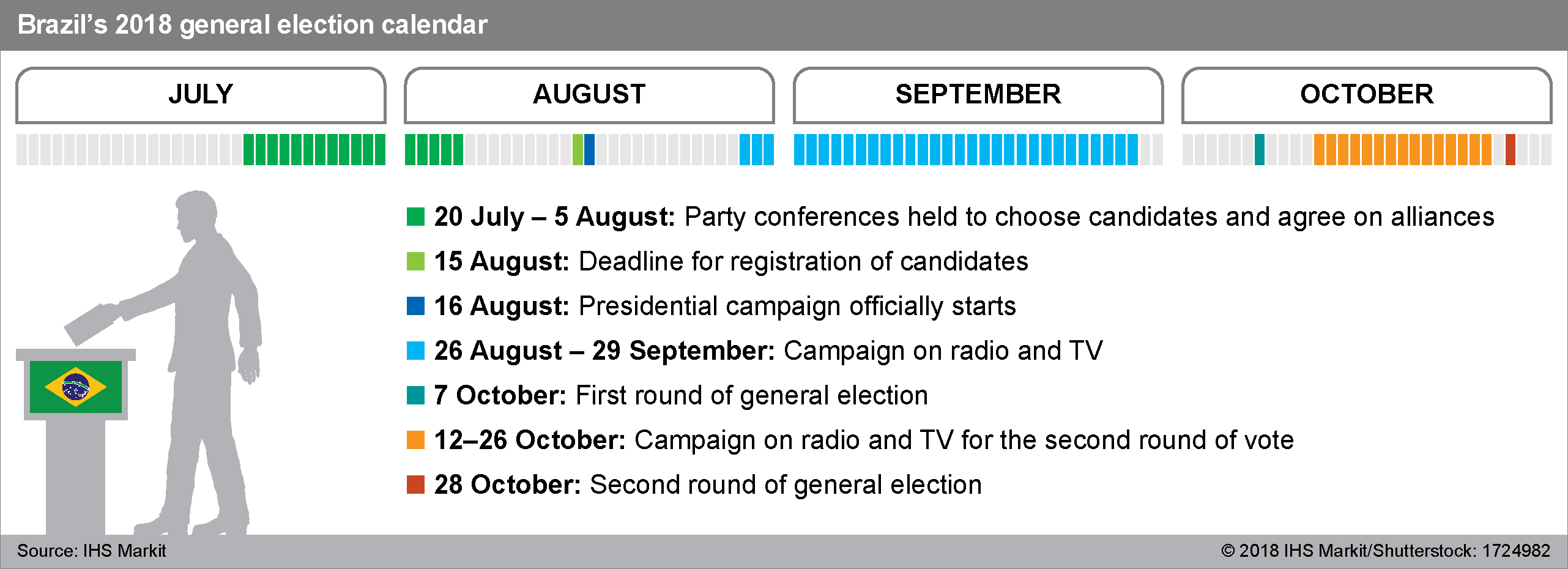

The campaign officially starts in mid-August: until then political parties will focus on forming coalitions. Radio and television slots for competing candidates will be allocated according to political groupings' number of seats in Congress. This allocation is bound to be a decisive factor in the election, particularly because financing from the corporate sector is no longer legal in Brazil. Instead, parties would receive funding from a relatively modest electoral fund, financed by public money.

These new rules encourage candidates to seek coalitions that guarantee funding and greater TV and radio exposure. Such coalitions would make a significant difference for the prospects of outsiders like Jair Bolsonaro and Marina Silva, who lack solid party structures. Bolsonaro has invited Senator Magno Malta of the Party of the Republic (PR, Partido da República) to be his vice-presidential candidate. PR's 37 congress seats would boost Bolsonaro's prospects and would bring increased TV time and funding. Silva is in a weaker position because, unlike Bolsonaro, she has publicly refused any potential alliance with mainstream parties or any party associated with the current Michel Temer government.

The fight to lure the "centrão"

The support of the so-called "centrão" (big center) has become the most coveted prize for any candidate. This is an alliance of mid-sized non-ideological centrist parties, with about 200 seats in the Lower House. Over the last three years it has become a highly influential faction in Brazilian politics. Unified backing from this group for one of the main candidates could prove decisive. Since they are non-ideological and tend to make deals based on bureaucratic quotas in a future government, the group could back almost any candidate. Ciro Gomes, Geraldo Alckmin, Jair Bolsonaro and the pre-candidate of MDB, former Finance Minister Henrique Meirelles, are all negotiating with "centrão" leaders.

Outlook and implications

The high number of candidates, new campaigning rules, the influence of charismatic former president Lula, and the difficulties of all candidates in assembling coalitions make the October 2018 election the most unpredictable since 1989.

Clear indicators of likely political and policy direction only will emerge in early September, once definitive coalitions are established and the key indicator of who PT decides to endorse. This also applies for the center-right, where Geraldo Alckmin, the candidate favored by the markets, is struggling to assemble a coalition with sufficient electoral traction. This delay improves the prospects for "outsider" candidates and risks undermining Alckmin's chances of reaching the second round. This is increasing concerns among international investors, damaging both the country's credit outlook and the real, which has depreciated sharply since January 2018. An outsider victory would make it very difficult to implement austerity measures and the pension reform Brazil needs to restore policy credibility and business confidence.

Key developments likely to affect the political landscape include a possible agreement between PSDB and the MDB around a ticket led by Alckmin, with Meirelles as his vice-president. This would constitute a strong coalition, able to rely on the support of state machinery, committed to economic reforms and with the backing of the business sector. Alternatively, a coalition of Bolsonaro with some of the Centrão parties or an alliance of Ciro Gomes with the PT also would change the campaign dynamics significantly, increasing the chances of an outsider victory.