Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jun 18, 2018

Banking sector developments in Bangladesh

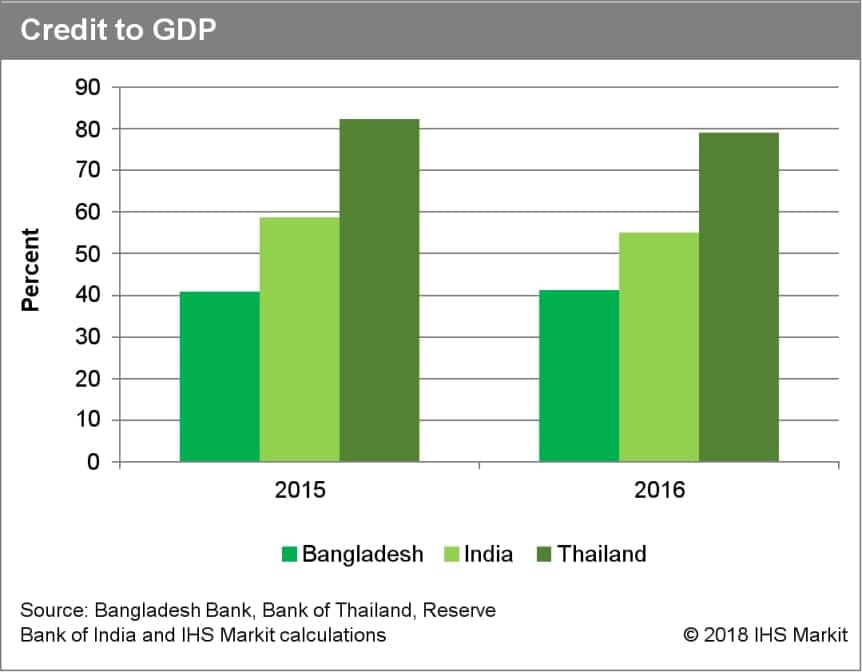

Although Bangladesh has adopted many internationally recognized frameworks, such as Basel III capital requirements, its banking sector remains underdeveloped and is characterized by poor asset quality and low capital buffers. Compared with neighboring India and Thailand, Bangladesh's banking sector is very small relative to its economy. As of the third quarter of 2017, banking sector assets were equivalent to only 62.6% of GDP, compared with 86.8% in India and 117.8% in Thailand. At the same time, banking services usage, as measured by credit to GDP, is low, at around only 40%. However, Bangladesh's banking sector is growing at a very rapid rate. Bangladesh is still managing the fallout of a late-2010 stock market crash that brought into light regulatory, supervisory, structural, and operational weaknesses within the country's banking sector.

Fast credit growth, state-directed lending, and loan

restructuring raise credit risk

The low-credit-depth of Bangladesh's banking sector

suggests that the three-year average credit growth of 14.8% in 2016

does not suggest a high-credit-risk environment by itself. However,

we judge credit risk in the sector to be elevated owing to

loan-restructuring practices, historically weak

credit-risk-management practices, concentrated loan books, exposure

to single large borrowers, and government-directed pressure on

state-owned banks' lending decisions. Furthermore, the sector is

plagued by long and difficult legal processes to recover loans,

especially with "habitual defaulters" - a term referred to by IMF's

preliminary statement for its 2018 Article IV report.

We see credit risks as being concentrated in several sectors. For the "ready-made garment" industry, we are concerned because most of the garments are exported (around 80% of exports from the country are garment-related). These loans are susceptible to currency fluctuation although the recent depreciation of the taka against the US dollar should provide some support. The other concern is its susceptibility to global trends, as seen in 2017. The credit risk of this industry depends on global economic trends and the industry's own competitiveness because of the low barrier to entry for manufacturing ready-made clothes. This industry's share of total NPLs was 10.4% in 2016, similar to its share of total loans. However, when restructured loans are included, this rises to more than 35%, suggesting one-third of total loans extended to this industry are of poor quality. However, in the near term, Bangladesh's cheap labor still provides support for the industry.

High NPL ratio with even-higher stressed loans

ratio

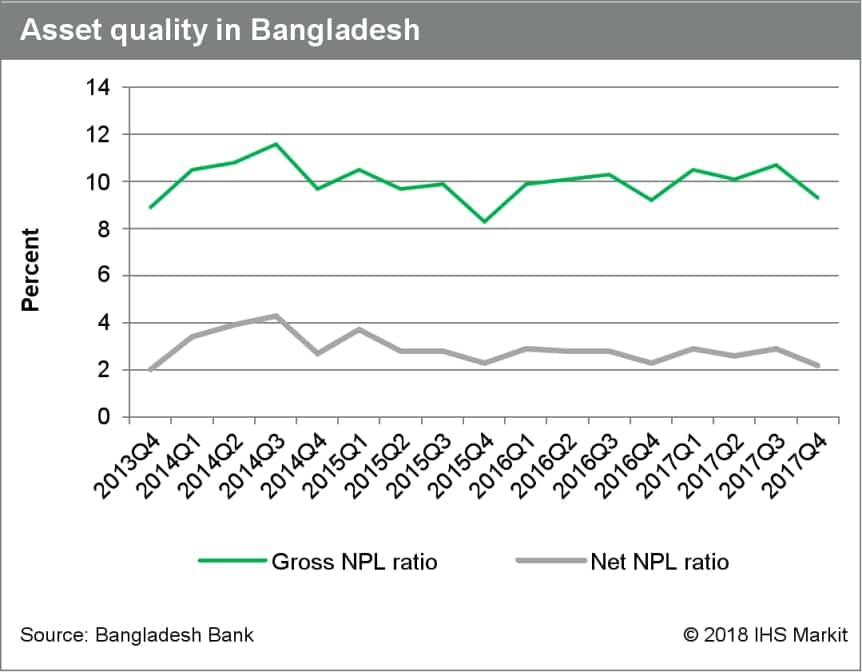

Our concerns for asset quality are exacerbated by low bad-loan

provisioning. Based on data from BB, the NPL ratio has been around

10% since at least 2013; it was last reported at 10.7% in the third

quarter of 2017. Considering the double-digit credit growth

recorded in the same period, this suggests the stock of NPLs has

risen considerably. BB also reported a net NPL ratio of 2.9% at the

same time, suggesting the bad-loan provisioning ratio is only at

72.9%. We judge that the restructuring (rescheduling) of loans and

large loan concentration are likely to put pressure on

asset-quality indicators in the near term, considering restructured

loans accounted for 10.5% of total loans in 2016 (latest).

Loan restructuring remains an issue despite the regulatory forbearance was designed to expire in June 2014. To take account of this issue, we rely on the stressed advances ratio released by BB to understand better the actual impairment levels in Bangladesh. The latest ratio released by BB in its 2016 Financial Stability Report showed the stressed advances ratio as 17.2%. By our rough calculations, we estimate the NPL ratio to be closer to 20% (10.7% NPL ratio plus 10.5% restructured loans). However, there have been some development and recognition of the NPL issues. In late 2016, BB asked banks to classify their loans more stringently and also came up with plans to reduce NPLs for those lenders reporting NPL ratios above 5%. However, banks have not made material change to loan recovery law as suggested by the IMF in 2017 and 2018 to help alleviate asset-quality issues.

High capital pressure from low provisioning and

below-regulatory-minimum capital ratios

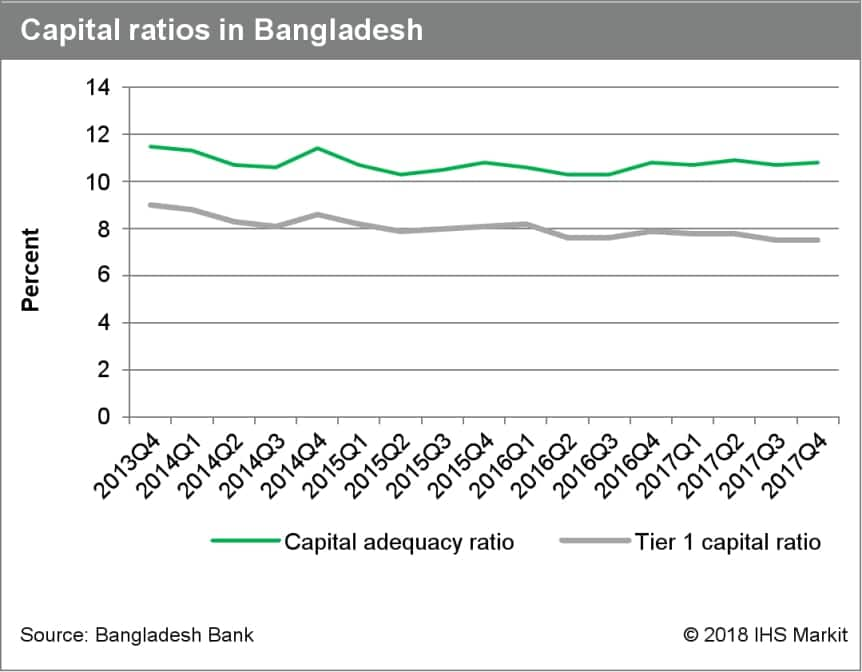

BB reported a capital adequacy ratio (CAR) of 10.7% and a

Tier 1 capital ratio of 7.5% for the banking sector. The CAR is

below the requirement of 11.25% (including capital conservation

buffer) in 2017, suggests as a sector, it is undercapitalized (BB

reported that at least seven banks, accounting for 17.8% of total

sector assets, were noncompliant with the regulatory minimum in

2017). The latest data reported by the IMF provided insights into

which banks these are most likely to be: state-owned banks fell

significantly off the mark, with the CAR at 5.9% in 2016, while

private-sector banks' CAR was on average above required levels at

12.4%. This is further exacerbated by the low bad-loan provisioning

of close to 70% using headline NPL ratio, or only around 20%

provisioning for our conservative estimated of NPL ratio being

20%.

Further inspection shows that two state-owned banks recorded negative CARs in 2016, implying effective insolvency. Basic Bank, received a government capital injection at the end of 2016. We believe additional capital injections into other state-owned banks are likely in the near term. Although BB's transition to a Basel III capital framework is encouraging from a regulatory standpoint, we believe the transition is likely to necessitate capital injections on the part of the government, particularly to state-owned banks that have historically been relying on repeated capital injections from the government. The capital positions of banks are increasingly precarious, as from 2018 banks will be required to maintain a higher CAR (including the capital conservation buffer) and Tier 1 ratio of 11.875% and 6%, respectively. Capital pressure is unlikely to dissipate in the near-term because of continued credit growth and credit-risk increase.

Implicit guarantee on deposits could keep structural

liquidity position moderate

The government has an implicit guarantee for deposits

placed in state-owned banks, in addition to the deposit guarantee

scheme that protects BDT100,000 (USD1,177.4) of deposits (including

interest). This helps explain the discrepancies in the structural

liquidity position (loan-to-deposit ratio: LDR) of state-owned

banks compared with privately owned banks, with state-owned banks

attracting far more deposits because of the implicit guarantee.

Overall, the sector exhibited an LDR of 74.8% when last reported by

BB in the third quarter of 2017, lower than the 78.7% we calculated

for 2016. The major development in this area regards the drop of

1.5 percentage points in the LDR maximum to 83.5% from June 2018,

which is likely to curb credit growth slightly in privately owned

banks or encourage better interest rates on deposits to increase

deposits. However, inter-bank liability of only 4.5% suggests

contagion risk is low at present.

Wide performance difference between state-owned and

privately-owned banks

The central bank reported that there were 57 commercial

banks (identified as scheduled banks locally) at the end of 2017.

The top five banks accounted for 30.8% of total sector assets.

Among the 57 banks are 6 state-owned banks, 9 foreign banks, 32

local privately-owned banks, 8 Islamic banks, and 2 specialized

banks. In terms of proportion of outstanding lending, local private

banks accounted for around 50%, state-owned banks for around 20%,

foreign banks for less than 5%, specialized banks for around 3%,

and Islamic banks for close to 2%.

There is large performance disparity between privately- and state-owned banks, with the latter often exhibiting worryingly high impairment ratios and low (even negative in some banks) capital ratios. Based on state-owned banks' very high levels of impairment and lower-than-required levels of capital, it is likely that they will continue to require government support in the coming years. The private sector, on the other hand, although still plagued by the lack of strong governance due to BB's lack of supervisory power, fares better.

The four state-owned banks - Sonali, Janata, Agrani, and Rupali - have worse asset quality, lower capital adequacy ratios, and lower profitability (in terms of return on average assets, or ROA) than their large, privately owned peers. Two in particular, Agrani Bank and Rupali Bank, have very weak performance with notably negative ROA ratios and very high NPL ratios (above 20%). The combined effects of the very low NPL coverage ratio and low capital adequacy ratios mean that these banks are subject to further downward pressure on their capital. On the other end of the spectrum is Islami Bank, a privately owned Islamic bank that has much stronger performance, with a low NPL ratio and a very high NPL coverage ratio (close to 200%).

Outlook and implications

As noted, the concentration of loans and state-approved

restructuring of loans are the most worrying trends for credit

risks. These have helped feed NPLs, however the most concerning

issue across the banking sector is the undercapitalization of

state-owned banks, owing much to state-directed lending. The low

provisioning and likely much higher NPL ratio, coupled with the

fact that as a sector banks are undercapitalized, suggest some

banks are likely to fail in the near term. We judge the government

is likely to injection capital to stop a collapse in confidence in

the sector because despite the implicit guarantee, cash withdrawal

could further undermine liquidity buffers. Going forward, we judge

that the sector is likely to be better managed and regulated. We

believe the most important improvements would come from better

credit-risk management, removal of state-directed lending

decisions, and reversal of regulatory forbearance on loan

restructuring to allow for a more transparent view of the sector's

health, but none of these have been mooted as policies so far.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanking-sector-developments-in-bangladesh.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanking-sector-developments-in-bangladesh.html&text=Banking+sector+developments+in+Bangladesh+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanking-sector-developments-in-bangladesh.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Banking sector developments in Bangladesh | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanking-sector-developments-in-bangladesh.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Banking+sector+developments+in+Bangladesh+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanking-sector-developments-in-bangladesh.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}