Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Jul 09, 2021

Australia-China Trade Tensions: The Great Escape?

China-Australia trade tensions have escalated significantly in 2020-21, with Australian exports of goods having been impacted by an increasing array of trade policy actions by China. China applied trade measures during 2020 to a large number of major Australian exports, including coal, wine, seafood and barley. Meanwhile key Australian services exports to China, notably international education and tourism, have also been disrupted as a result of Australia's hard border closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

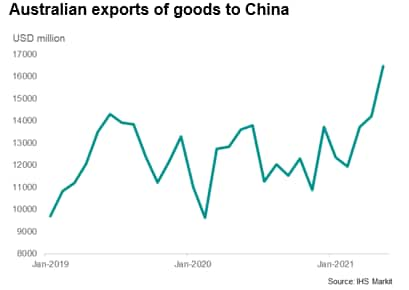

Australia's vulnerability to disruptions in bilateral trade with China has increased substantially since 2000, as China has rapidly become the largest export market for Australia. These developments have resulted in mounting concerns about the economic implications to the Australian economy from a protracted disruption of Australian exports to China. Yet, despite China's trade measures, Australian exports of goods worldwide rose by 11% year-on-year (y/y) in May 2021. Notably, Australian merchandise exports to China in May 2021 were up 16% y/y, despite the escalation in bilateral trade frictions.

The escalation of trade tensions between China and Australia

Mainland China has become by far the largest export market for Australia, accounting for a third of Australia's total goods and services exports in 2019, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The importance of mainland China as an export market for Australia has increased dramatically over the past two decades, with Australian exports to mainland China having grown from just AUD 8.8 billion in the 2000-01 financial year to AUD 153 billion in the 2018-19 financial year.

Consequently, Australia has become increasingly vulnerable to trade sanctions by China on its exports. Due to escalating frictions on a wide range of issues, bilateral trade tensions have increased significantly during 2020-21. As former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd rather colourfully said recently, "Australia has been on the rough end of the pineapple in the relationship with China".

With key Australian exports of services such as international education and tourism to mainland China already having come to a halt due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the hard border closures, the focus of China's trade policy actions has been on Australian exports of goods.

Even during 2019, there had been some temporary disruptions of Australian coal shipments to certain Chinese ports, with long delays in permission to unload Australian coal cargoes at Chinese ports. These disruptions became much more severe during the second half of 2020.

In May 2020, the Chinese government also imposed punitive tariffs on Australian exports of barley to China, amounting to a combined 80.5% tariff on Australian barley. China's General Administration of Customs said barley shipments from Australia would be halted after they stated that pests were found on multiple occasions.

There has been a more intense escalation in trade measures by China in relation to Australian products since early November 2020. These measures, which include unofficial guidelines to Chinese importers as well as other non-tariff measures such as customs procedures, have created considerable concern amongst Australian exporters of a wide range of products. The scope of the Chinese policy measures included beef, lobster and wine, three product categories for which China is Australia's largest end market.

Australia's economic performance

The Australian economy has rebounded strongly during the first half of 2021, helped by broad containment of domestic COVID-19 cases, despite intermittent lockdowns in various Australian cities. This has allowed an upturn in domestic economic activity. As Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Governor Philip Lowe stated on 6th July 2021 in his speech on the RBA's Monetary Policy Decision:

"The Australian economy is on a positive path. Output is now above its pre-pandemic level and more Australians have a job than they did before the pandemic. The unemployment rate has returned to its pre-pandemic level, underemployment has declined and job vacancies are at a high level. So we are in a much better position than we thought we would be in."

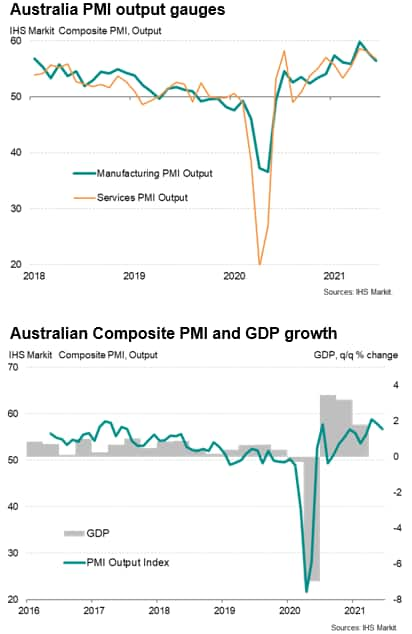

Survey data confirm this upbeat assessment. The seasonally adjusted IHS Markit Manufacturing Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) recorded a buoyant 58.6 in June after May's record of 60.4. Despite the slowing of growth momentum, the manufacturing sector expanded at a strong pace compared to historical levels. Manufacturing output and new orders both rose for the twelfth successive month in June as market confidence remained solid in line with the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, although the extended lockdown in Victoria, which carried into June, affected operating conditions at some firms.

Australia's service sector also continued to expand at a strong pace in June, albeit affected by the latter part of the lockdown in Melbourne. The seasonally adjusted Services PMI Business Activity Index eased to 56.8 in June from 58.0 in May, signalling a continued rise in activity, though at a somewhat softer pace.

Australian exports in H1 2021

Recent official economic data have likewise shown encouraging strength. In May 2021, Australian merchandise exports were up 34% y/y, helped by base year effects as well as the strong growth in iron ore exports. Metal ore exports were up 63% y/y in May 2021, amounting to an increase in export value of AUD 7.4 billion compared to the same month a year earlier.

Exports of cereals also showed a substantial increase, rising by 180% y/y in May 2021, or up AUD 887 million in export value compared to May 2020.

The Australian manufacturing sector has also been boosted by improving export orders, which have shown a gradual upturn since the second half of 2020.

Despite the sharp escalation in bilateral trade frictions, Australian exports of goods to China actually recorded an increase of 16% y/y in May 2021. This was heavily driven by exports of iron ore, which rose by 20% y/y in value terms.

This reflects the strong rebound in Chinese industrial output since the first quarter of 2020, as well as supply side disruptions to iron ore production in other key producers, notably Brazil.

China is also a key market for Australian coal exports, and this has also been heavily disrupted by China's trade measures. During the second half of 2020, Australian coal shipments to China faced severe disruptions, with many shipments delayed at Chinese ports.

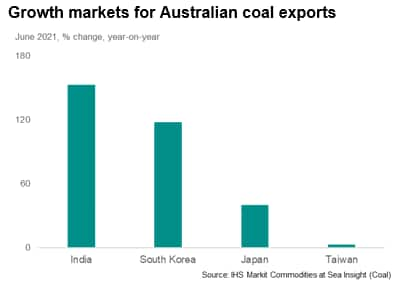

The situation for coal exports to China deteriorated further during the first half of 2021. According to IHS Markit's Commodities at Sea Insight (Coal) report of 7th July 2021, there were no Australian coal shipments to mainland China in June 2021, compared with 11.9 million tonnes shipped in 2020. However, despite the collapse in Australian coal exports to China, Australian coal exports worldwide in June 2021 were at 32.9 million tonnes, down just 2.4% y/y.

Although Australian coal exports to mainland China were at a standstill in June 2021, the collapse in Chinese import demand has been largely offset by substantial increases in Australian coal exports to Japan, India, South Korea and Taiwan. Australian coal exports have also been buoyed by strong global traded thermal coal prices, with Newcastle thermal coal export prices having reached almost a thirteen-year high.

Australian export outlook

Over the past decade, many Australian export industries had become increasingly vulnerable to potential disruptions of market access to China due to rising concentration risk to that single market. This had become well recognized as a key risk by Australian policymakers and industry leaders in recent years although little concrete policy action was taken by companies to reduce their vulnerability to such trade concentration risk.

While Australia is unlikely to embark on any kind of tit-for-tat retaliatory trade measures, particularly given the very asymmetric bilateral trade relationship with China, the policy implications for Australia are that most Australian export industries with significant exports to mainland China will be urgently and rather belatedly looking at diversification strategies to reduce their vulnerability to future Chinese trade policy measures. It seems clear that any hopes of a return to "business as usual" have become a rapidly receding mirage.

However, the Australian government has lodged a formal complaint at the World Trade Organization in June 2021 in regard to China's anti-dumping duties applied to Australian wine. Australia had also lodged a complaint at the WTO in 2020 in relation to China's anti-dumping duties on Australian barley, and the WTO has agreed in May 2021 to establish a dispute resolution panel on this matter.

In the near-term, the overall negative shock to Australian exports from a macroeconomic perspective has been mitigated by the strong growth in iron ore export values as well as diversification of coal exports to other key markets in Asia. Indeed, Australian exports of goods actually showed a strong positive growth rate in May 2021 compared to the same month a year ago.

However, the process of trade diversification for the wider cross-section of industries with high exposure to China is likely to be gradual, over a protracted period of time, as different industries look to diversify into a wider range of export markets.

Moreover, market expectations are for some future easing over the medium-term of the very high current levels of world iron ore prices, as recovering Brazilian production and potential new sources of iron ore supply dampen current high world price levels. However, for now, Australian iron ore exporters are making hay while the sun shines.

Australia's membership of the CPTPP and RCEP regional free trade agreements is likely to help this process of export market diversification over the next five to ten years. The RCEP trade deal, which was signed in November 2020, includes the ten ASEAN member nations as well as Japan and South Korea. The CPTPP free trade agreement, which has already been implemented, includes Japan, Canada and Mexico. The UK has also applied for accession to CPTPP, with South Korea have also signalled potential interest, which would further deepen the importance of CPTPP as a key multilateral trade deal.

Furthermore, Australia also has a growing network of free trade agreements with key trade partners. One important recent FTA is the bilateral free trade agreement with Indonesia, the Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, which is expected to significantly improve market access for Australian exports to this nation, which is one of the world's largest emerging markets.

Despite the tremendous challenges of significantly diversifying its export markets, Australia will benefit from its proximity to many large consumer markets across the Asia-Pacific region. India is already the world's sixth largest economy, with its consumer market forecast to grow strongly over the next decade. The ASEAN region has also become a very large consumer market with a total regional GDP of USD 3 trillion, around double the size of Australia's domestic consumer market, with a population of over 600 million. Consequently, ASEAN and India are likely to be high priorities for Australia's export diversification strategy over the decade ahead.

Rajiv Biswas, Asia Pacific Chief Economist, IHS Markit

Rajiv.biswas@ihsmarkit.com

© 2021, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faustraliachina-trade-tensions-the-great-escape-July21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faustraliachina-trade-tensions-the-great-escape-July21.html&text=Australia-China+Trade+Tensions%3a+The+Great+Escape%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faustraliachina-trade-tensions-the-great-escape-July21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Australia-China Trade Tensions: The Great Escape? | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faustraliachina-trade-tensions-the-great-escape-July21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Australia-China+Trade+Tensions%3a+The+Great+Escape%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faustraliachina-trade-tensions-the-great-escape-July21.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}