Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Nov 12, 2021

By Rajiv Biswas

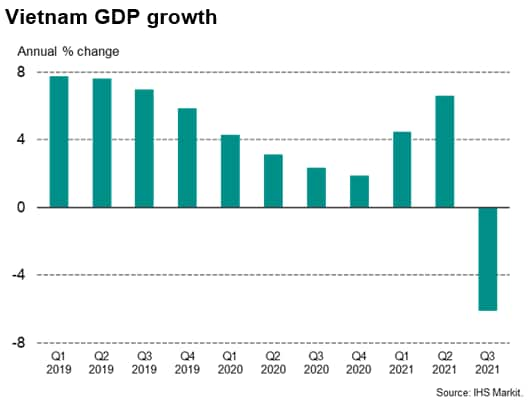

In 2020, Vietnam was one of the most resilient economies in the Asia-Pacific region to the shockwaves from the global COVID-19 pandemic, with very low numbers of COVID-19 cases throughout most of 2020. Economic growth was strong in the first half of 2021, with GDP in the second quarter of 2021 rising by 6.6% year-on-year. However, a severe COVID-19 Delta wave engulfed the nation in mid-2021, resulting in a sharp contraction in GDP growth in Q3 2021.

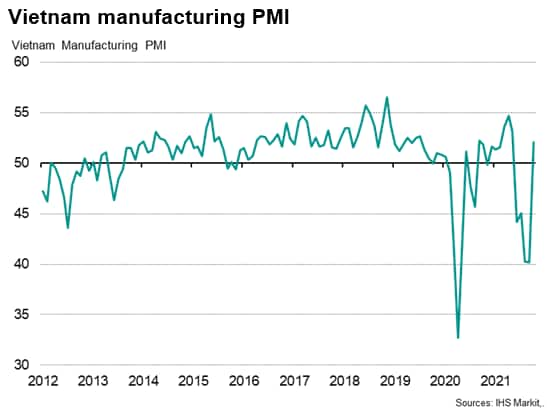

Latest economic data for Q4 2021 are showing signs of recovering economic momentum. The IHS Markit Vietnam Manufacturing PMI for October 2021 showed a strong rebound in the manufacturing sector. However, the economic recovery still faces headwinds due to a renewed upturn in daily new COVID-19 cases as well as continuing supply chain disruptions.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Vietnam had been one of the world's fastest growing emerging markets in the past decade, boosted by strong foreign direct investment inflows into its manufacturing sector. The pace of economic growth slightly exceeded 7% in both 2018 and 2019. Rapid growth of manufacturing exports and large new inflows of foreign direct investment have been important growth drivers for Vietnam, notably driven by rapid expansion in the textiles and electronics sectors. Total electronic and electrical manufacturing exports accounted for 33% of total merchandise exports in 2019, with textiles, clothing and footwear accounting for a further 19.4%.

Total foreign direct investment inflows reached USD 20.4 billion in 2019, up 6.7% year-on-year, driven by strong investment by multinationals in establishing new manufacturing production facilities in Vietnam. Samsung has been a key investor, with total foreign direct investment into Vietnam of around USD 17 billion in the decade to 2018. Vietnam has become the biggest foreign production hub for Samsung Electronics, which booked USD 66 billion of sales in 2019 out of its Vietnamese operations, which was equivalent to around 25% of Vietnam's GDP. Around 50% of Samsung's smartphones and tablets are produced in Vietnam and exported globally. Samsung Vietnam has also built its largest R&D centre in Southeast Asia near Hanoi.

However, economic growth momentum moderated significantly in 2020, due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. For calendar 2020, the Vietnamese economy still recorded positive growth of 2.9% y/y, compared with a 7.1% GDP growth rate in calendar 2019. Despite the moderation in growth momentum, Vietnam was one of the very few industrial economies in the Asia-Pacific region that achieved economic expansion in 2020, as the world economy slumped into a recession. Disbursed FDI remained resilient in 2020 despite the pandemic, at around USD 20 billion, down only 2% on 2019. However, FDI commitments fell more sharply, by 25% y/y, to USD 28.5 billion.

With the domestic pandemic having remained contained, economic growth momentum strengthened in the first half of 2021. GDP growth in the second quarter of 2021 rose by 6.6% y/y, improving on the 4.65% y/y growth recorded in the first quarter of 2021. A key driver of economic growth momentum was the rapid growth of exports, which rose be 28.4% y/y in the first half of 2021. The strong performance of industrial exports also boosted the industrial sector, with industrial production up 9.3% y/y in the first half of 2021. FDI inflows in the first half of 2021 remained resilient, at USD 9.2 billion, up 6.8% y/y.

However, with the highly transmissible Delta strain of COVID-19 having spread rapidly throughout Southeast Asia in mid-2021, a severe new Covid Delta wave hit Vietnam in Q3 2021. As a result of the rising pandemic wave, the government authorities put in place strict lockdown restrictions for many provinces. Ho Chi Minh City, a key commercial hub, faced very severe restrictive measures for a wide range of activities, including on public transport and public gatherings, as well as non-essential business activities.

Consequently, Vietnam's GDP contracted by 6.17% y/y in Q3 2021, with consumer spending, construction activity and manufacturing production hit severely by the lockdown measures.

This led to a sharp decline in business conditions for manufacturers during June and July. The IHS Markit Vietnam Manufacturing Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) plummeted from 53.1 in May to 44.1 in June, showing the most severe deterioration in business conditions for over a year and ending a six-month period of growth. Although the July PMI reading edged up to 45.1, this remained well below the 50.0 mark signaling neutral business conditions, indicating continuing contraction in the manufacturing sector. By September, the headline PMI had fallen further, to 40.2.

However, as daily new COVID-19 cases started to decline during the second half of September and early October, easing lockdown restrictions allowed the reopening of many factories, resulting in a sharp rebound in the IHS Markit Vietnam Manufacturing PMI to 52.1 in October.

During Q3 2021, severe disruption to supply chains were noted by firms in the PMI survey results, with the extent of delivery delays reaching the highest level since the survey began more than a decade ago. Companies linked longer lead times to difficulties with transportation both domestically and internationally due to the pandemic, as well as raw material shortages. Manufacturers were also faced with surging input costs. The rate of input price inflation accelerated to the fastest since April 2011. Input costs increased at the fastest pace since April 2011 and at one of the sharpest rates in the survey's history. Higher freight charges were widely reported, adding to the inflationary pressures caused by raw material shortages. Higher costs for raw materials such as iron and steel, products imported from China and freight charges were all reported by firms.

Shortages of labour also contributed to rising backlogs of work, as migrant workers returned to their home provinces and towns during the protracted lockdowns and widespread factory closures.

Issues around staffing levels remained despite the wider return to growth. Employment continued to fall markedly in October, with a number of firms indicating that some of their staff members had returned to their hometowns during the latest wave of the pandemic and had yet to come back to their place of work.

The impact of factory closures related to the pandemic has become increasingly widespread during July and August. Over 100 seafood processing factories were closed in southern Vietnam during periods in August, while over one-third of textiles and garments factories in Vietnam are also reported to have been temporarily closed in August and September due to the pandemic.

Samsung Electronics has reported that in Vietnam, which is a key electronics manufacturing hub for the firm, there were production disruptions in certain places due to lockdowns that affected operations. However, the firm managed to mitigate the disruptions by shifting production to other parts of their global manufacturing supply chain.

Toyota announced an estimated 40% drop in global auto production in September due to the impact of global semiconductors shortages as well as disruption to supply chains in Southeast Asian manufacturing hubs, including Vietnam. Toyota temporarily halted several auto assembly lines in Japan for periods during July and August due to disruptions to supply of auto parts from Vietnam.

The COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown measures and temporary company closures were all mentioned by firms participating in the survey as factors leading to sharp reductions in both output and new orders during Q3 2021.

In August, total merchandise exports fell by 2.3% month-on-month (m/m), as the impact of factory closures due to the escalating pandemic began to impact more significantly upon manufacturing production. The decline in August exports was heavily impacted by a 15% m/m decline in exports of textiles and garments and a 40% m/m decline in exports of footwear, due to widespread factory closures. Exports of wood products fell by 39% m/m, while exports of fisheries products fell by 30% m/m.

Nevertheless, due to the strength of Vietnamese exports during the first half of 2021, total Vietnamese merchandise exports for the first eight months of 2021 were still up by 21.8% y/y, according to Vietnam Customs data. Exports to the US were buoyant, rising by 31.8% y/y, while exports to China also rose strongly, by 22.3% y/y. Exports to the EU rose by 14% y/y during the same period.

Although Vietnam's merchandise exports have been very resilient in 2020 and in the first eight months of 2021, exports of tourism services have collapsed since March 2020 due to the impact of international travel bans, including Vietnam's own ban on international travel. Prior to the pandemic, the tourism economy had been growing strongly in recent years, with international tourist visits to Vietnam in 2019 having reached 18 million trips, up 16% y/y. The protracted disruption of international tourism has hit Vietnam's service sector exports badly in 2020-21. The impact on the overall tourism economy had been mitigated by the significant contribution of domestic tourism to the overall industry, while the domestic pandemic remained contained. However, with the severe Covid Delta wave resulting in intensifying lockdown restrictions since mid-2021, domestic tourism activity has also been badly hit.

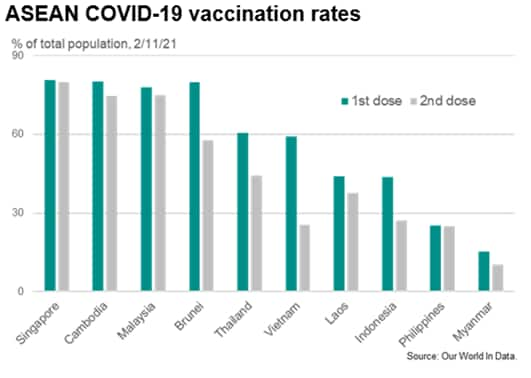

The Vietnam's COVID-19 vaccine rollout program lagged significantly behind the rate of vaccination progress in many OECD nations as well as in most other APAC emerging markets during the first half of 2021. Even by late August 2021, the first dose vaccination rate for Vietnam had only reached 15% of the total population, compared with 80% in Singapore, 56% in Malaysia and 50% in Japan. The fully vaccinated share of the Vietnamese population was still extremely low by late August 2021, at only 3%.

However, the pace of vaccination rollout has risen very rapidly in September and October, with the first dose vaccination rate rising to 63% by 8th November, while the fully vaccinated share of the population has risen to 31%.

Nevertheless, with the fully vaccinated share of the total population still at around only one-third, Vietnam still remains vulnerable to escalating new COVID-19 transmission, which could result in renewed lockdown measures.

The economic impact of the pandemic is expected to recede during 2022 as vaccination rollout becomes more widespread across the population of Vietnam. An additional new favorable factor is the development of tablets by Pfizer and Merck to treat those patients who become COVID-19 positive and are vulnerable to severe illness. The combination of increasing vaccination rollout and having supplies of these new tablets are expected to help to contain the pandemic during 2022.

Over the medium-term outlook for the next five years, a number of key drivers are expected to continue to make Vietnam one of the fastest growing emerging markets in the Asian region.

Firstly, Vietnam will continue to benefit from its relatively lower manufacturing wage costs relative to coastal Chinese provinces, where manufacturing wages have been rising rapidly over the past decade.

Secondly, Vietnam has a relatively large, well-educated labor force compared to many other regional competitors in Southeast Asia, making it an attractive hub for manufacturing production by multinationals.

Third, rapid growth in capital expenditure is expected, reflecting continued strong foreign direct investment by foreign multinationals as well as domestic infrastructure spending. For example, the Vietnamese government has estimated that USD 133 billion of new power infrastructure spending is required by 2030, including USD 96 billion for power plants and USD 37 billion to expand the power grid.

Fourth, Vietnam is benefiting from the fallout of the US-China trade war, as higher US tariffs on a wide range of Chinese exports have driven manufacturers to switch production of manufacturing exports away from China towards alternative manufacturing hubs in Asia.

Fifth, many multinationals have been diversifying their manufacturing supply chains during the past decade to reduce vulnerability to supply disruptions and geopolitical events. This trend has been further reinforced by the COVID-19 pandemic, as protracted supply disruptions from China during February and March 2020 created turmoil in global supply chains for many industries, including autos and electronics.

For example, the Japanese government has introduced a subsidy program in 2020 for Japanese companies to help reduce supply chain vulnerability by relocating production out of China either back to Japan or to certain other designated nations. The Japanese government has allocated an estimated 220 billion yen for the supply chain reshoring program in Japan's supplementary budget for the 2020 fiscal year, equivalent to around USD 2.1 billion. An additional 23.5 billion yen were allocated for supply chain diversification to other selected countries, which includes ASEAN, India and Bangladesh. Vietnam has been one of the preferred destinations for Japanese firms choosing to shift their production to the ASEAN region in the first round of subsidy allocations announced by the Japanese government.

Vietnam is also set to benefit from its growing network of free trade agreements. As a member of the ASEAN grouping of nations, Vietnam already has benefited considerably from the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA), which has substantially removed tariffs on trade between ASEAN member countries since 2010. ASEAN also has a network of free trade agreements with other major Asia-Pacific economies, most notably the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area which entered into force in 2010. This network of free trade agreements has helped to strengthen Vietnam's competitiveness as a low-cost manufacturing export hub.

The EVFTA is a key new free trade agreement that will boost Vietnam's exports and foreign direct investment inflows. The EVFTA is an important boost to Vietnam's export sector, with 99% of bilateral tariffs scheduled to be eliminated over the next seven years, as well as significant reduction of non-tariff trade barriers. For Vietnam, 71% of duties were removed when the EVFTA took effect on 1st August 2020. Vietnam's exports to the EU rose by 14% y/y in the first eight months of 2021. The scope of the EVFTA is wide-ranging, including trade in services, government procurement and investment flows. An EU-Vietnam Investment Protection Agreement has also been signed which will help to strengthen EU foreign direct investment into Vietnam when it is implemented.

Vietnam will also benefit from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) free trade agreement, which will be implemented from 1st January 2022. The fifteen RCEP countries are the ASEAN ten nations, plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. Vietnam has already ratified the RCEP agreement and will therefore benefit immediately from the date of RCEP implementation. The RCEP agreement covers a wide range of areas, including trade in goods and services, investment, e-commerce, intellectual property and government procurement.

The U.S. deficit for trade in goods with Vietnam reached USD 55.8 billion in 2019, with the deficit widening by 41.2% compared to 2018. This was slightly mitigated by the USD 1.2 billion surplus in favor of the US for trade in services, but still left the overall bilateral trade deficit at USD 54.5 billion in 2019.

In 2020, the US trade deficit with Vietnam for trade in goods further widened, reaching USD 69.7 billion.

Reflecting the persistent large bilateral trade surplus that Vietnam has with the US, the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) announced on 2nd October 2020 that the US government has launched an official investigation into acts, policies, and practices by Vietnam that may contribute to the undervaluation of its currency and the resultant harm caused to US commerce, under section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act.

As part of its investigation on currency undervaluation, USTR consults with the US Department of the Treasury as to issues of currency valuation and exchange rate policy. The US Treasury has informed the US Department of Commerce that Vietnam's currency was undervalued by 4.7% in 2019, partly due to intervention by the Vietnamese government. In December 2020, the US Treasury named Vietnam as a "currency manipulator".

USTR has also launched an investigation into Vietnam's acts, policies, and practices related to the import and use of timber that is assessed to be illegally harvested or traded.

However, in its April 2021 semiannual Report on Macroeconomic and Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States, the US Treasury determined that with reference to the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, there was insufficient evidence to make a finding that Vietnam manipulates its exchange rate for either of the purposes referenced in the 1988 Act, and dropped its labelling of Vietnam as a "currency manipulator".

Nevertheless, consistent with the 1988 Act, the US Treasury considers that its continued enhanced engagements with Vietnam, as well as a more thorough assessment of developments in the global economy as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, will enable the US Treasury to better determine whether Vietnam intervened in currency markets to prevent effective balance of payments adjustment or gain an unfair competitive advantage in trade.

US government concerns about currency manipulation have been further addressed following a bilateral agreement in July 2021 between the US and Vietnam whereby Vietnam has committed to refrain from competitive devaluation of the dong. The agreement was announced in a joint statement by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and State Bank of Vietnam Governor Nguyen Thi Hong.

Due to the impact of the latest COVID-19 Delta wave, the pace of Vietnam's economic growth is expected to moderate to 2.3% in 2021, compared with the 2.9% growth rate recorded in 2020. A strong recovery in GDP growth momentum is forecast for 2022, at a pace of 6.3% y/y, as increasing vaccine rollout helps to gradually contain the pandemic and allows a gradual reopening of international tourism.

However, a key uncertainty in the near-term outlook is the extent and duration of the current wave of new COVID-19 cases that is hitting the nation. If daily new COVID-19 cases rise sharply again, this would pose a significant further risk to the near-term outlook for domestic demand. There would also be the added risk of renewed protracted disruption to manufacturing output if widespread COVID-19 clusters are again detected in major manufacturing facilities or logistics supply chains, as occurred in July and August 2021. Furthermore, unless Vietnam can significantly ramp up its fully vaccinated rate in coming months, it remains vulnerable to new Covid outbreaks.

Despite these near-term risks, over the medium-term economic outlook, a large number of positive growth drivers are creating favorable tailwinds and will continue to underpin the rapid growth of Vietnam's economy. This is expected to drive strong growth in Vietnam's total GDP as well as per capita GDP.

Vietnam's total GDP is forecast to increase from USD 270 billion in 2020 to USD 433 billion by 2025, rising to USD 687 billion by 2030. This translates to very rapid growth in Vietnam's per capita GDP, from USD 2,785 per year in 2020 to USD 4,280 per year by 2025 and USD 6,600 by 2030, resulting in substantial expansion in the size of Vietnam's domestic consumer market.

Vietnam's role as a low-cost manufacturing hub is also expected to continue to grow strongly, helped by the further expansion of existing major industry sectors, notably textiles and electronics, as well as the development of new industry sectors such as autos and petrochemicals.

For many multinationals worldwide, significant supply chain vulnerabilities have been exposed by the protracted disruption of industrial production in China as well as some other major global manufacturing hubs during the COVID-19 lockdowns. This will drive the further reshaping of manufacturing supply chains over the medium term, as firms try to reduce their vulnerability to such extreme supply chain disruptions. With US-China trade and technology tensions still remaining high, this is likely to be a further driver for reconfiguring of supply chains. A key beneficiary of the shift in global manufacturing supply chains will be the ASEAN region, with Vietnam expected to be one of the main winners.

Rajiv Biswas, Asia Pacific Chief Economist, IHS Markit

Rajiv.biswas@ihsmarkit.com

© 2021, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location