Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Jun 13, 2022

By Fotios Katsoulas and Rahul Kapoor

European importers have been avoiding crude oil shipped from Russia, as a response to the invasion of Ukraine. This has driven a rather remarkable switch in the direction of Russian crude oil flows towards Asia, mostly India and China. Assuming the Continent will fully avoid Russian seaborne flows at some point, this would affect average monthly flows of 55 million barrels (around 1.8 million b/d), or up to 85 million barrels (2.8 million b/d), if barrels of Kazakhstan are included.

With India already having increased the volumes it absorbs from Russia to more than 900,000 b/d (from just 30,000 b/d last year), it becomes rather probable for the country to be able to import 30 million barrels of Russian crude oil on a monthly basis (or around 1 million b/d). Meanwhile, China could increase its imports from Russia (primarily referring to additions in shipments from Russia's European ports) by 15 million barrels on a monthly basis versus last year's activity, equivalent to additions of half a million b/d.

This scenario would increase global demand for crude oil tankers by 3.5% (1.8% related to India and 1.7% driven by additional flows to China).

A more optimistic scenario, where India increases its flows from Russia to 45 million barrels per month, or 1.5 million b/d, and China to 25 million barrels per month or 830,000 b/d, would cause global demand for crude oil tankers to expand by 5.6% (2.8% related to India and 2.8% to China).

Meanwhile, European importers are expected to gradually avoid supplies of refined products shipped from Russia, which could drive a growth near 4.2% for clean tanker shipping demand.

According to S&P Global Commodities at Sea, Russia was typically shipping around 30 million barrels of refined products to Europe on a monthly basis, based on last year's activity. From these volumes, around 20 million barrels each month referred to gasoil/diesel, equal to up to 700,000 b/d.

The average journey from Russia to Europe lasts 8 days, while those to West Africa and Latin America last 25 days and 30 days respectively, on average.

Assuming 60% of these volumes will be shipped to West Africa and 40% to Latin America, then this would drive an increase in demand for clean tanker shipping by around 2.2% and 2% each, or 4.2% in total versus last year's levels.

MRs have been primarily used for clean flows from Russia to Europe, typically requiring 106 MR voyages each month, with 3 for LR1s and 3 for LR2s.

The switch would provide a boost to flows on LR1s and LR2s instead.

There is no doubt that the change of direction in Russian oil flows, for both crude oil and refined products, will have a significant impact on the demand for tanker shipping.

The insurance ban adds pressure against Russian shipments

Meanwhile, the tension between the West and Russia, after the invasion of Ukraine, extends into other parameters shaping the operations of the shipping industry.

A major issue to consider has been the recent news on the potential insurance ban, by both the UK and the European Union, on any tankers carrying Russian oil around the world, which could sharply affect the global shipping industry fundamentals.

This ban, which would come into effect half a year after the oil ban, could cause severe pressure against Russian oil exports from the Black Sea and the Baltic, potentially driving a decline in exports, down up to a million b/d.

Without insurance, buyers would not ship the oil, unless governments establish mechanisms to cover insurance domestically, as it happened before with Iranian cargoes.

The alternative observed so far, with Russia shipping mostly to China and India, would have to rely on tonnage controlled or owned domestically.

This justifies the recent decision by Unipec to charter more than 10 tankers so far, to transport more Russian oil to China.

The switch of Russian oil shipped to China and India instead of Europe is estimated to require around 30 Aframaxes (including those employed for lightering), 50 Suezmaxes and most importantly more than 40 VLCCs.

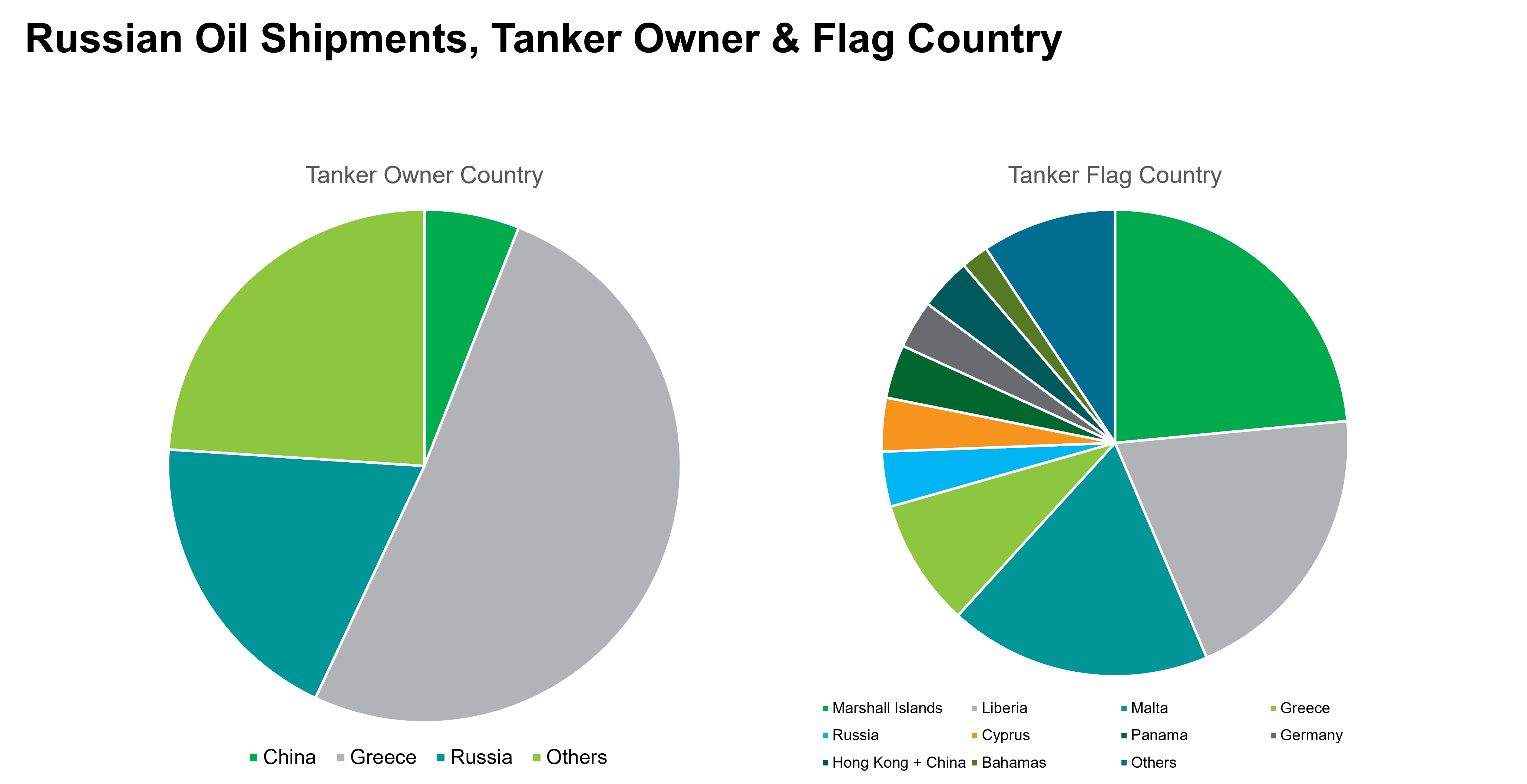

Securing suitable tonnage might prove a difficult task, after the insurance ban. Any of the ships carrying crude oil from Russia would be avoided in most other international oil routes. European shipowners control more than a third of the available tonnage, with Greeks having dominated the transport of Russian cargoes so far.

President Putin recently referred to plans to establish a fully independent and integrated supply chain from production to end customer, including insurance, which would enable Russia to maintain or even expand its exports to Asia.

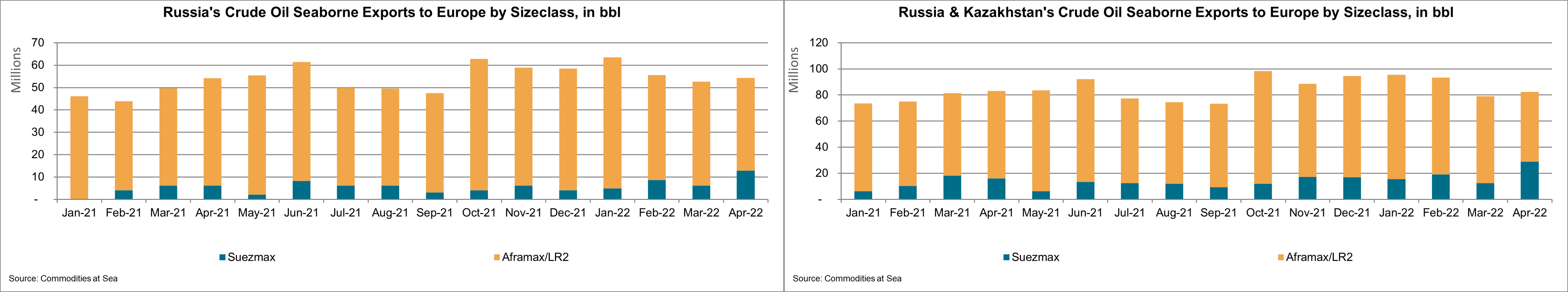

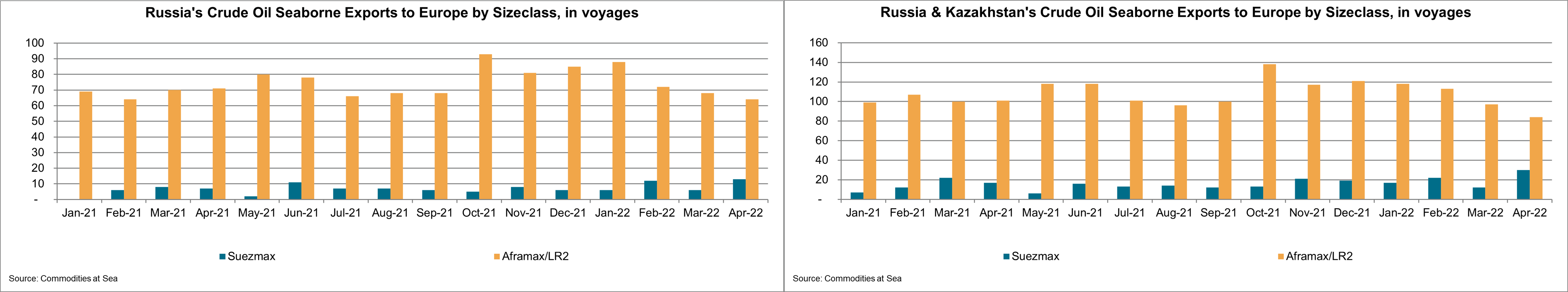

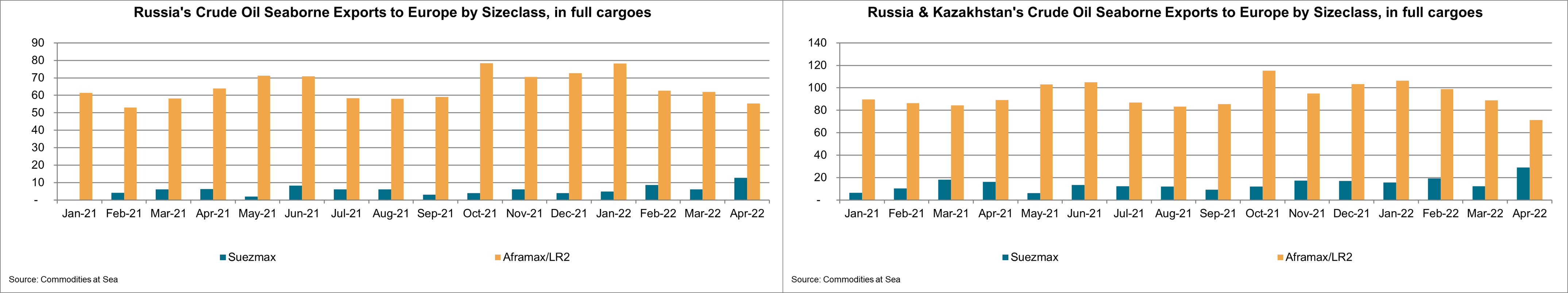

Russia has been one of the major crude oil suppliers to most European importers, with an average of 53 million barrels shipped to the continent each month in 2021, with activity increased to around 57 million barrels per month, up 7.5% versus last year's average. Most of these volumes were loaded in the Baltic or the Black Sea, with 84% of all these barrels carried on Aframaxes. The rest has been typically carried on Suezmaxes, with only small insignificant volumes loaded on Panamaxes or MRs. Flows including barrels of Kazakhstan shipped from Russian ports to Europe reach 84 million barrels per month.

Russian crude oil shipments to Europe have a rather significant source of demand for crude oil tankers, typically requiring 75 Aframax voyages and around 7 Suezmax voyages on a monthly basis (or 110 and 15 respectively, if barrels of Kazakhstan are included). As some of these voyages refer to cargoes smaller than the typical capacity targeted to be employed by each sizeclass, the average requirement for full cargoes has been estimated around 65 per month for Aframaxes and around 6 for Suezmaxes, or 93 and 14 respectively if barrels of Kazakhstan are included.

Source: Commodities At Sea

An Aframax carrying Russian crude oil to European destinations has been estimated to need 7 days to complete her voyage, for loadings between Jan-21 and Apr-22. However, the average duration is pushed to 8.5 days, if barrels of Kazakhstan are included. This is primarily driven by the slightly longer average haul to be covered for ships carrying CPC Blend.

Source: Commodities At Sea

A Suezmax employed within the same regional trade routes (Russia to Continent) spent an average of 9 days to complete her voyage, or 12 days if barrels of Kazakhstan are included. All metrics provided have taken into account all international shipments from Russia to the Continent, loaded between Jan-21 and Apr-22.

Crude oil shipments from Russia to the continent have generated 8% of the global demand for Aframaxes carrying crude oil in 2021 (excluding domestic movements) and 9.6% in the period from Jan-22 till Apr-22. If barrels of Kazakhstan are included, the market share is pushed to 14.7% for 2021 and 15.7% for this year so far.

Source: Commodities At Sea

The same routes have been responsible for around 1% of the global demand for Suezmaxes, which is pushed to 2.7% for 2021 and 3.6% for 2022 so far, if barrels of Kazakhstan are included.

The big question has been what the impact for the shipping demand would be if Europe proceeds with its plans to ban Russian crude oil imports, as a response to the invasion of Ukraine.

Russia has so far managed to maintain its seaborne exports, or even to report on-month gains, according to Commodities at Sea, primarily shipping more crude oil from the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea. However, it becomes clear that several European importers have been reducing their exposure to Russian barrels, since early March.

There have never been any VLCCs loading directly from any of Russia's biggest crude oil exporting ports in the Baltic and the Black Sea (Novorossiysk, Primorsk and Ust-Luga), with local port restrictions allowing ships up to Suezmaxes to call at their berths, according to Market Intelligence Network.

Any Russian barrels carried to Asia on VLCCs have been typically loaded their cargoes from other ships (Ship-to-Ship), usually within European waters, such as near the Danish or Dutch coasts.

China and India have been expected to dominate as the destinations for the additional volumes shipped to from Russia's European ports to Asia.

Russian shipments heading for China have approached 1 million b/d, while exports to India have jumped to historical highs, currently exceeding 750,000 b/d. India only absorbed around 30,000 b/d of Russian crude last year.

In parallel to the change in destination of Russian crude oil shipments, the shipping market has been experiencing several other transitions, such as the impact on the employment of the Russian tanker fleet, primarily controlled by state-owned shipping company Sovcomflot, which has been suffering severe pressure, since the employment of its Fleet has been falling sharply since sanctions were introduced.

Nearly 80% of the SCF fleet has remained ballast so far this month, as the sanctioned shipowner faces obstacles in getting vessels deployed.

In early May, 69 of the company's 89 tankers were ballast, with 14 vessels idle in the Far East, 11 in the Mediterranean, and 9 in the Black Sea.

Since the start of the invasion of Ukraine the SCF fleet employment has declined 21%, from nearly 1.4 billion tonne days during week beginning February 20 to 1.1billion tone days for the week beginning April 24.

European sanctions required banks and other financial institutions to cut ties with sanctioned Russian entities by mid-May. Additionally, the International Group of P&I Clubs has rescinded coverage for the sanctioned fleet, further complicating SCF's operations.

In addition, SCF was unable to make the interest payment due against its second tranche of Eurobonds, although it said it has $600 million in cash and is petitioning the Office of Financial Sanctions for a license to facilitate payment.

Reports indicate SCF has begun to liquidate members of its fleet in order to meet financial obligations to western financiers.

Focusing on the ships having recently lifted Russian crude oil, the majority refers to ships controlled by Greek shipowners (51%), Russians (19%) and Chinese (6%).

International relations become clearly crucial, taking into consideration the recent incident of two laden Greek tankers seized by Iranian forces near the Iranian coast.

This is believed to have been made in response to action taken by the Greek authorities in April, after the transfer of an Iranian oil cargo on board of an Iranian-flagged ship, previously controlled by Russian interests, to the US.

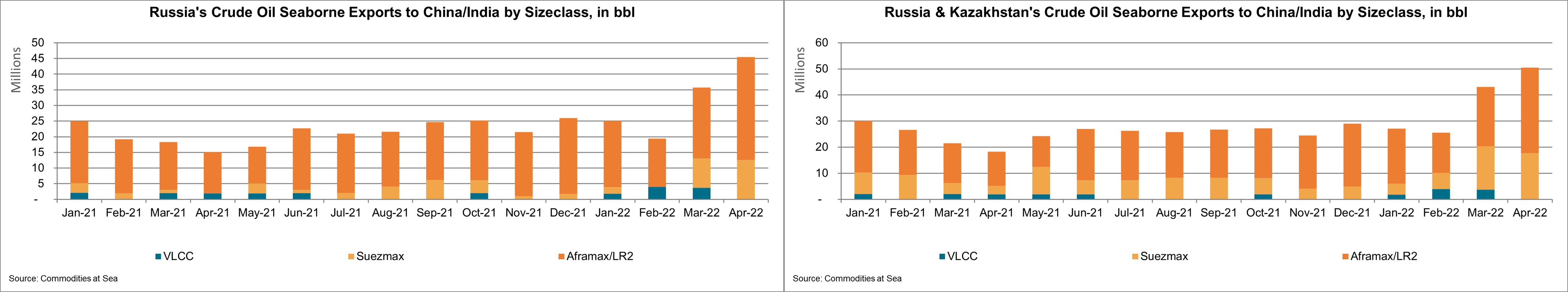

Average monthly shipments of purely Russian crude oil grades to China and India stood near 21 million barrels in 2021, but have already exceeded 31 million barrels this year, with April's activity at 45 million. Aframaxes carried 85% of these flows in 2021, but with their market share having fallen to 75% so far this year. Suezmaxes have recently gained in these routes, with their share pushed to 27% in the last couple of months, from just 11% in 2021. As more Russian crude oil from the Baltic and the Black Sea will be shipped to India and China in coming months, Suezmaxes are expected to be even more preferrable against Suezmaxes, while more VLCCs would probably consider lifting cargoes in these routes as well, especially if combined between cargoes from US Gulf to Europe and then Middle East Gulf to the Far East.

Source: Commodities At Sea

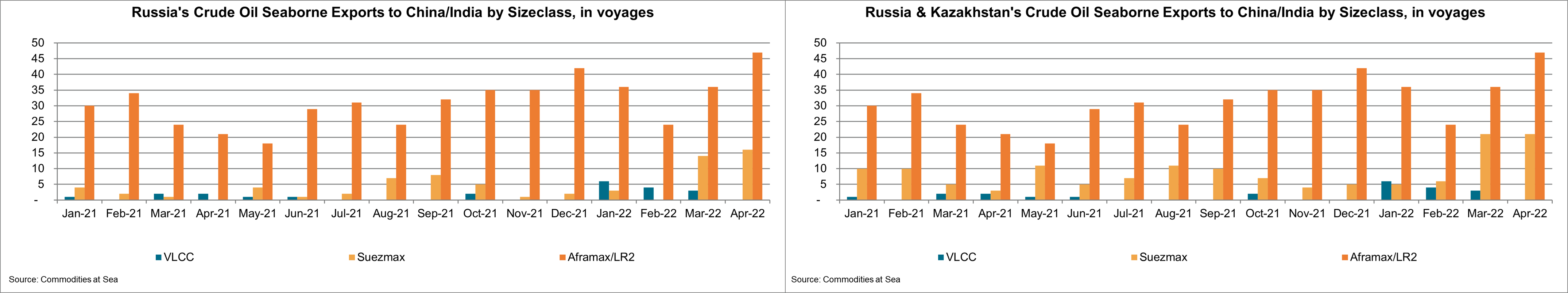

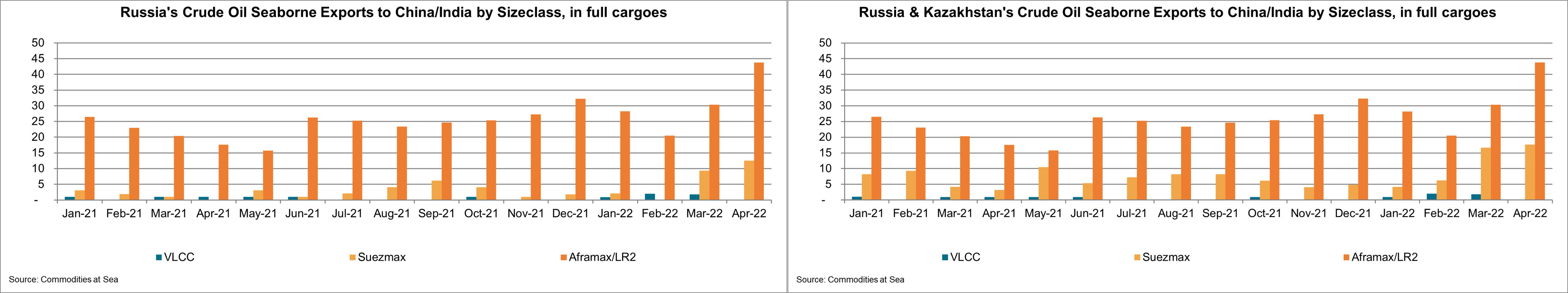

In terms of demand, flows from Russia to China and India have been typically requiring 30 voyages in 2021, a number pushed to 47 in April, with 19 of them referring to flows from Russia's European ports to the two Asian countries. A similar trend has been observed for Suezmaxes in recent months. It's worth highlighting that ships of both sizeclasses employed in flows from Russian Baltic and Black Sea to India and China have been utilizing most of their capacity.

Source: Commodities At Sea

A typical journey from the Baltic to India would require around 22 days, while a shipment from the Black Sea to India should complete within 30 days on average. The duration of voyages from the same origins to China would require around 37 and 45 days respectively.

Source: Commodities At Sea

Aframaxes carrying Russian crude oil to China and India were responsible for around 5% of the total demand of this sizeclass in 2021, a number pushed to 14% in April. Flows from Russia's European ports typically had no contribution to total demand, but their share reached 10% last month.

This clearly explains the potential benefit for the shipping demand if India and China prove to be a good alternative for Russian exports, expected to be further avoided across Europe in coming months.

Our assumptions on the longer distance to be covered by crude oil tankers refer to 20 days more for flows from the Baltic to India, instead of Europe, and 12 days more for voyages from the Black Sea.

Moreover, the voyage from the Baltic to China instead of Europe lasts 35 more days, while the one from the Black Sea to China instead of Europe requires 27 more days.

Assuming that two thirds of the additional flows to Asia will be loaded in the Baltic and the other third in the Black Sea, the additional voyage is 17.33 days more for ships heading for India and 32.33 more days for those moving to China.

For more insight subscribe to our complimentary commodity analytics newsletter

Posted 13 June 2022 by Fotios Katsoulas, Associate Director, Lead Analyst Tanker Shipping & Alternative Fuels, S&P Global Commodity Insights and

Rahul Kapoor, Vice President & Global Head of Shipping Analytics & Research, S&P Global Commodity Insights

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

How can our products help you?