S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Corporations

Financial Institutions

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Corporations

Financial Institutions

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Aug 02, 2022

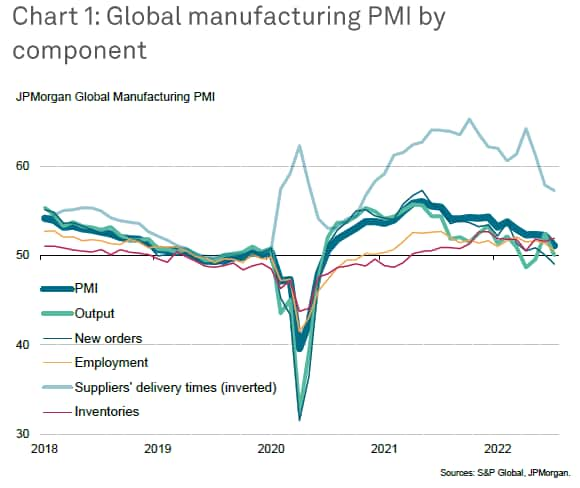

The JPMorgan Manufacturing Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™), compiled by S&P Global, fell from 52.2 in June to a two-year low of 51.1 in July. Output fell in the United States, Eurozone, UK and Japan, while mainland China saw a reduced rate of expansion and the rest of Asia as whole likewise mustered only modest growth. Forward-looking indicators, such as new order inflows and future output expectations, suggest the deterioration of performance will gather momentum in the near-term. Employment growth has also slowed to a near-standstill and looks set to weaken further.

In this analysis we look beyond the headline PMI to provide deeper insights into the current health of manufacturing around the world.

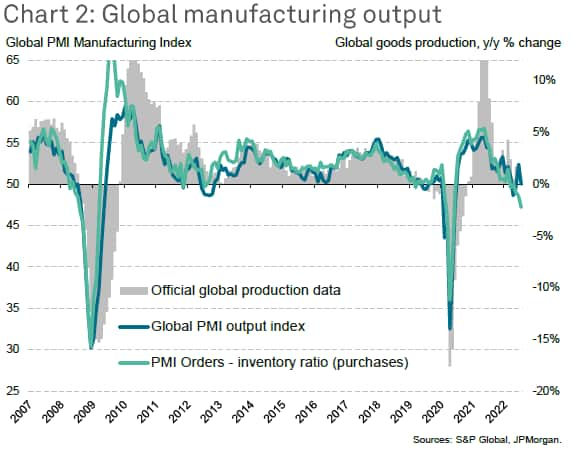

The global manufacturing PMI survey's Output Index, which acts as a reliable advance indicator of actual worldwide output trends several months ahead of comparable official data (see chart 2), signaled stalled production in July. The stagnation signals a faltering of the global production rebound seen in June from two months of contraction in April and May.

Much of this recent volatility can be attributed to business conditions in mainland China, where tightening COVID-19 restrictions severely limited production earlier the year but generated a strong rebound in June amid the subsequent loosening of containment measures. However, July saw some restrictions reimposed which, alongside subdued demand, led to a renewed weakening of production growth in China.

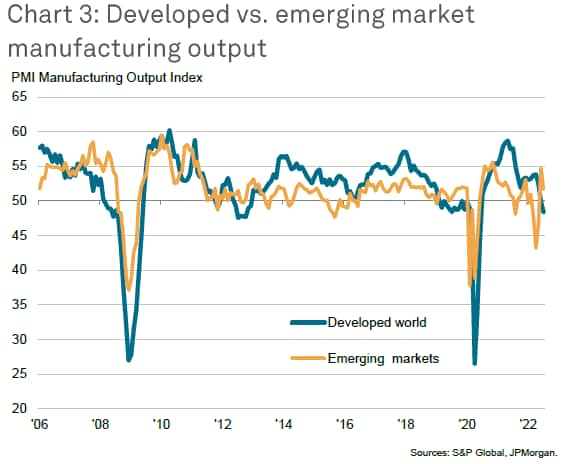

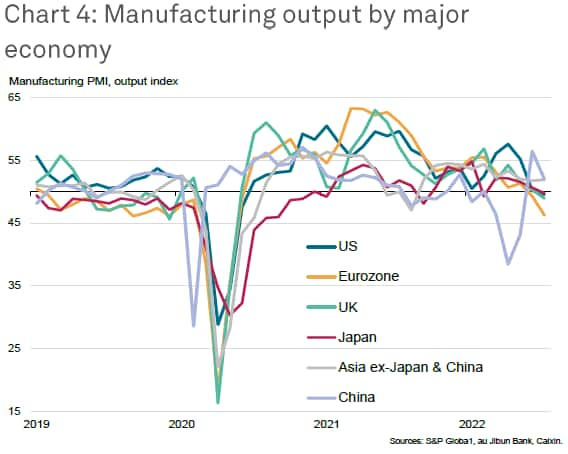

Production trends have meanwhile been deteriorating in the US, Japan and Europe in recent months, such that July saw factory output fall in the US, UK, Eurozone and Japan, causing developed world production to decline for a second month running, and at the fastest rate since June 2020.

While emerging market output rose to signal a further recovery from three months of Omicron-related declines, the rate of expansion slowed thanks to a near-stalling of order book growth.

The eurozone saw the steepest downturn of the major economies, and has now seen two consecutive months of decline, though the most severe falls in output in July were seen in Poland, Taiwan, Turkey, the Czech Republic, Mexico and Russia.

A worrying indication of the health of manufacturing was a decline in global exports for a fifth successive month in July, with the rate of decline accelerating to the second-fastest for two years (chart 5). Although only modest, the decline in exports is nevertheless one of the largest recorded over the past decade, excluding the early days of the pandemic. For the developed world, the decline was the second-steepest recorded since the global financial crisis, barring pandemic lockdown months.

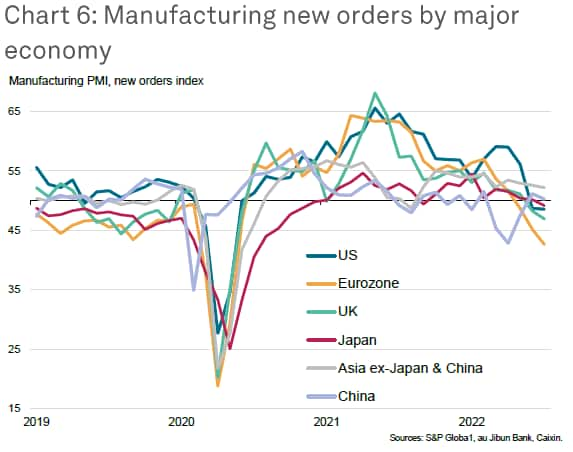

The worsening global trade picture contributed to an overall drop in new orders for manufactured goods for the first time in two years in July.

Of the world's major economies, an especially steep drop in new orders was recorded in the eurozone where, with the exception of pandemic lockdown months, the drop in demand signaled was the steepest since 2012. A steep fall in new orders was also reported in the UK, with declines also seen in the US and Japan. A near stalling of demand was meanwhile registered in mainland China while order book growth in the rest of Asia fell to the lowest since August 2021.

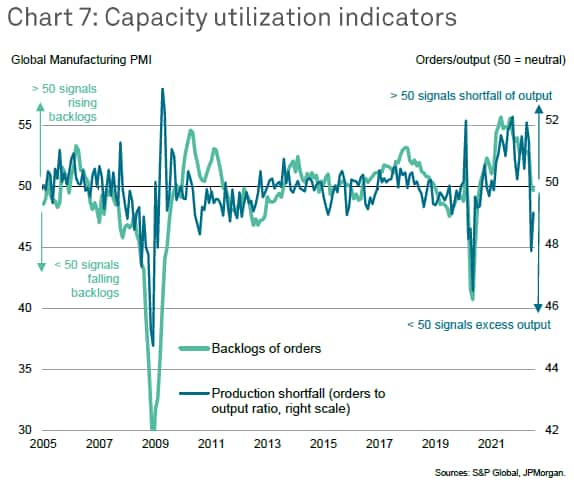

While at present the global production situation is one of stalled output, the deteriorating order book picture poses downside risks to the very near future. In particular, the global divergence of factory output and new orders remains unusually high (see chart 7), which explains why global backlogs of work have started to decline: a lack of new order inflows means output is being supported by firms working through orders placed in prior months. Absent a revival in new orders, this situation tends to result in firms scaling back operating capacity to align with the new weaker demand environment.

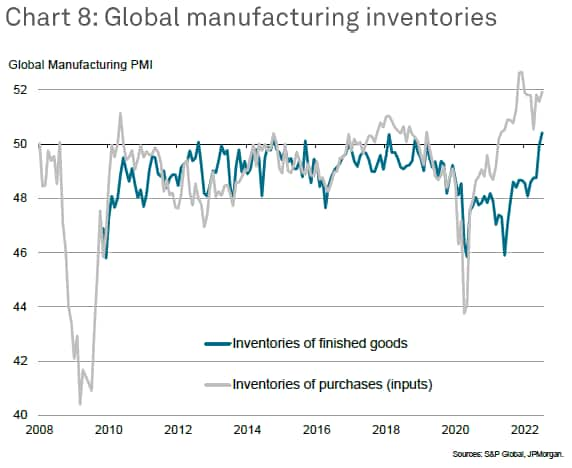

July also saw an increase in stocks of finished goods held by manufacturers of a magnitude not previously seen since comparable inventory data were first available in 2009 (see chart 10). The increase in part reflected a rise in the number of companies reporting higher inventories of unsold stock due to weaker than expected final sales in recent months.

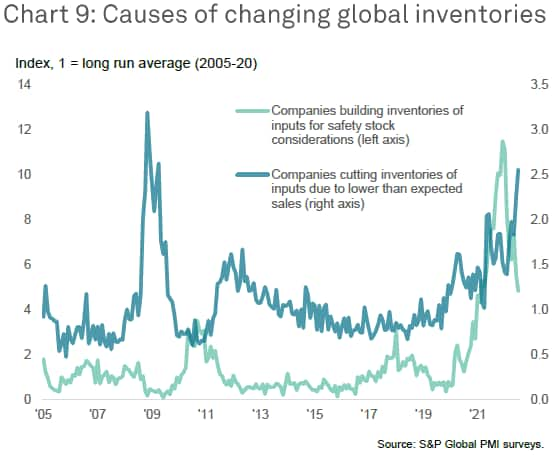

Inventories of raw materials and other inputs also rose at an elevated rate in July. While this was due in part to the further purchasing of inventories for safety stock considerations, the incidence of such precautionary stock building has fallen sharply in recent months (see chart 9), linked in part to fewer incidences of supply chain shortages. At the same time, we are observing a rise in the number of companies that are reporting higher input inventories due to less use in production amid weaker sales growth. Worryingly, the number of companies now cutting inventories due to concerns over slower than expect sales has risen globally to the highest since 2009.

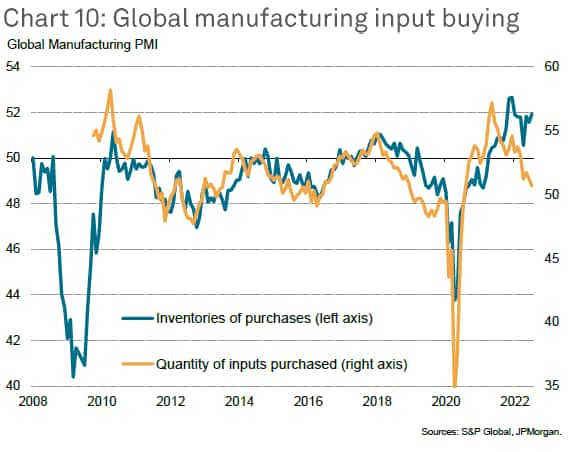

This move to inventory reduction, fueled by fewer concerns over supply shortages and increased worries of slumping sales, in turn led to the smallest increase in input buying by manufacturers globally in the current two-year sequence. The spread between inventory growth and input buying suggests that companies will further cut back on their input buying in coming months.

Similarly, with new orders falling and inventories rising sharply, firms are also likely to cut production in the coming months (as illustrated in chart 1). Barring pandemic lockdown months, the new orders-inventory ratio is at its lowest since the global financial crisis, signaling a potential substantial deterioration in the output trend in coming months.

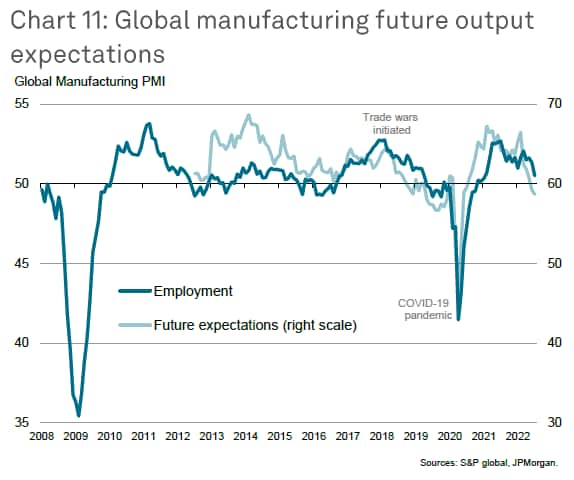

A slide into contraction for global manufacturing output is also signalled by the PMI's future output expectations index, which fell for a fifth consecutive month in July to reach its lowest since May 2020.

Companies' concerns were focused on the demand-destroying impact of the rising cost of living, as well as concerns over the Ukraine war and energy supply. Rising interest rates have also become an increasing cause for concern.

These reduced output expectations also look set to deter staff hiring in coming months (see chart 11), with the rate of manufacturing job creation having already slowed globally in July to the lowest since January 2021, the resulting overall monthly gain being only very modest.

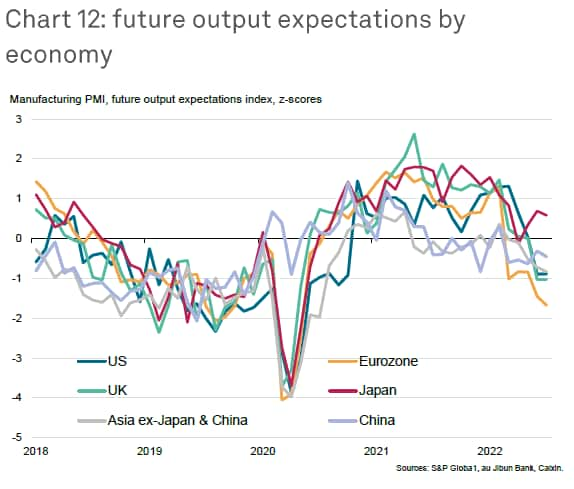

Compared to long-run averages, business confidence was again especially weak in the eurozone in July, reflecting the proximity of the Ukraine war and rising worries over energy supply, but also remained worryingly subdued in US, the UK and in Asia, with the exception of Japan, where the weaker yen has helped support expectations of growth in the coming year.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@spglobal.com

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.