Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — May 12, 2020

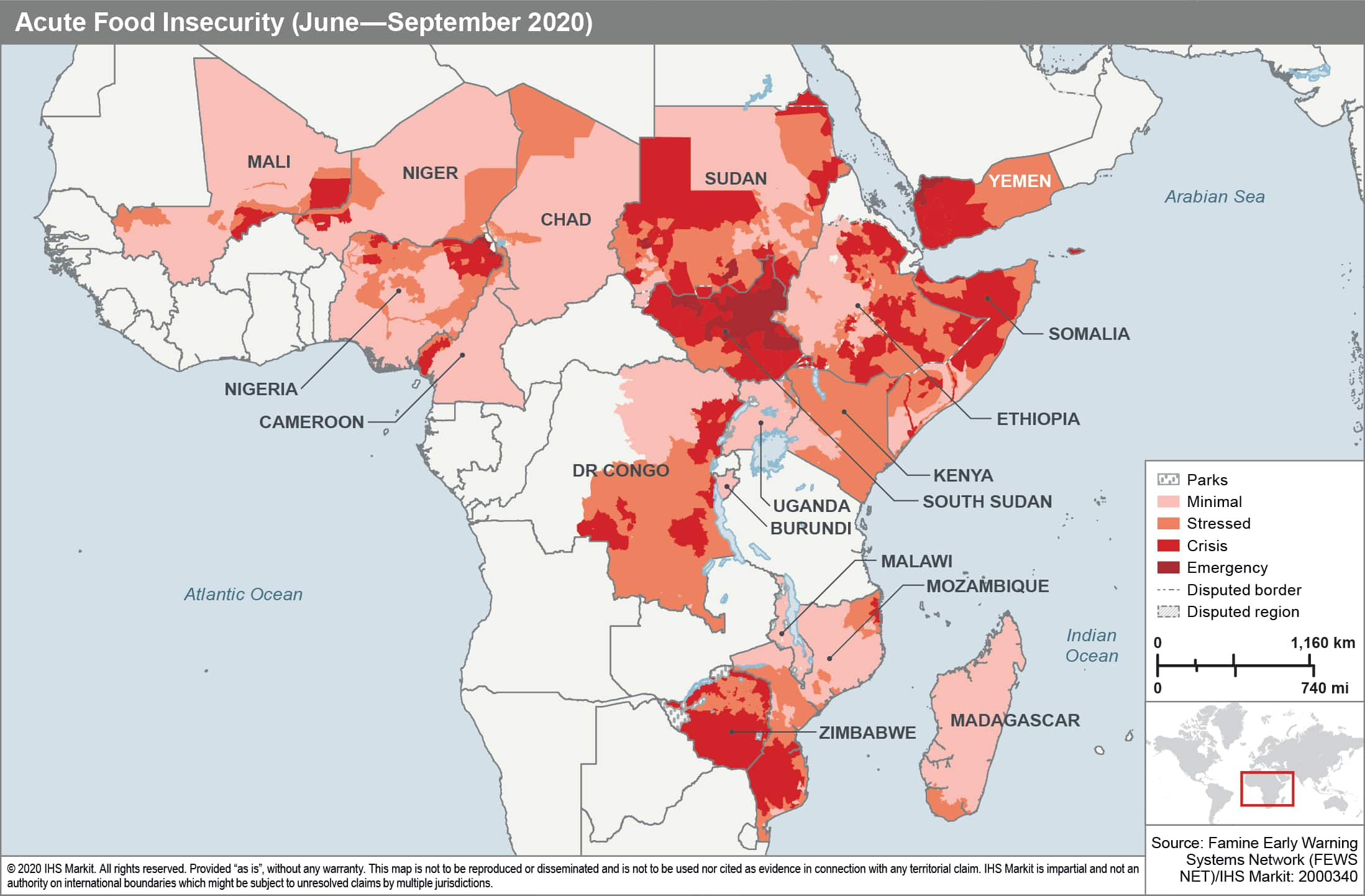

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), about 73 million people in the region were already facing a food crisis in 2019. The map below shows projected food insecurity severity in selected African countries based on the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC). Areas at highest risk of an acute food insecurity emergency are conflict-ridden regions in South Sudan and regions with a high share of internally displaced people in northeastern Nigeria. The deteriorating security situation in bordering areas of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso as well as in DRC increases the risk of food insecurity crisis in those areas. The Horn of Africa suffers from a desert locust infestation, which is expected to continue to destroy a large part of the region's food supply. Zimbabwe is at high risk of a food insecurity crisis due to a poor macroeconomic outlook and due to consecutive years of poor rainfall and drought that affected large parts of southern Africa.

Most of these regions rely heavily on humanitarian assistance to prevent food insecurity emergencies or famines. The COVID-19 pandemic will have detrimental effects on the delivery of humanitarian aid. Budgets of donor countries and organizations will shrink while the global economic recession prevails and resources will be diverted to health services and fighting the disease. In addition, movement restrictions and border closures hamper the mobility of supplies and staff.

Conflicts

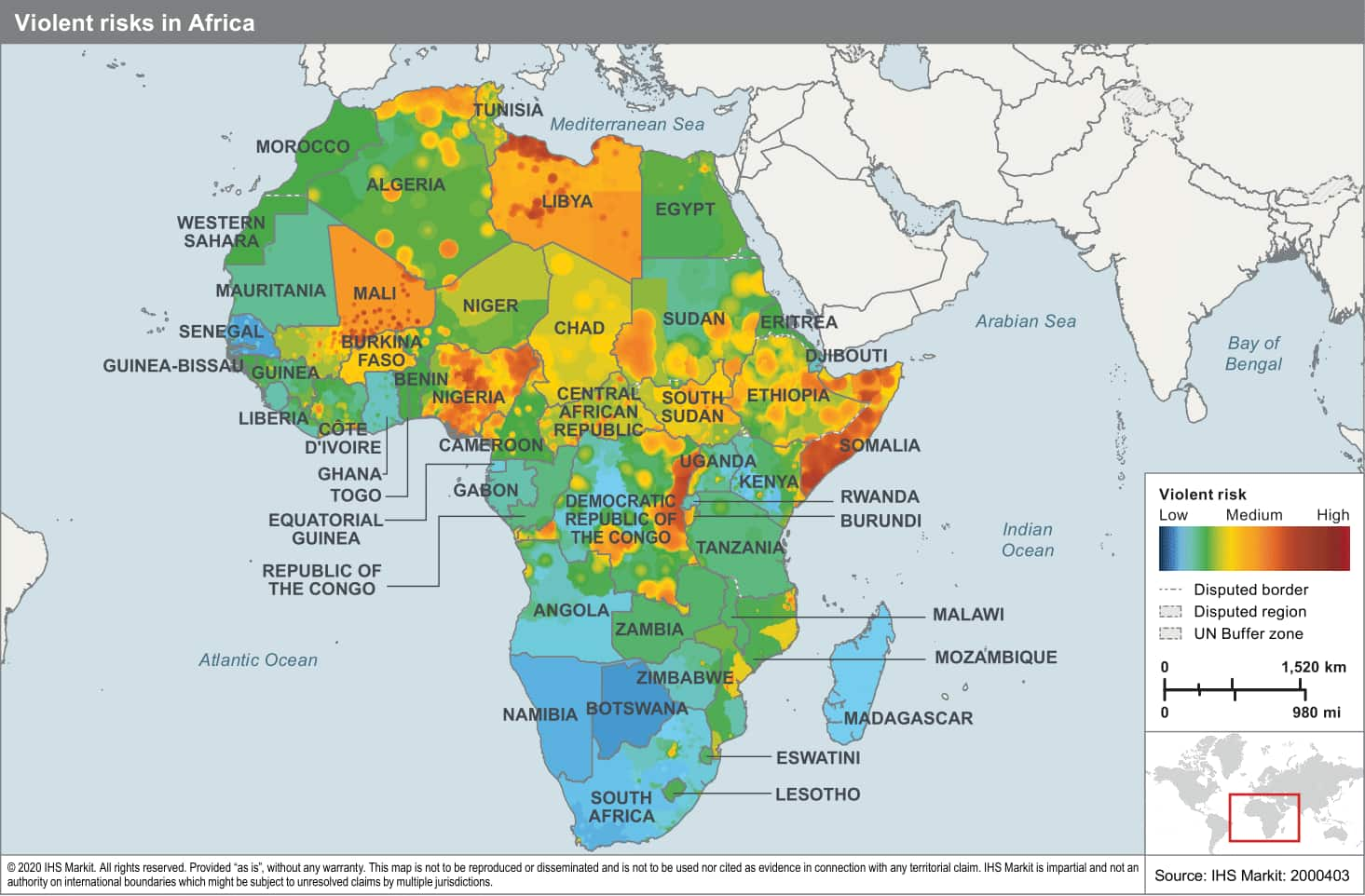

One of the main drivers of food insecurity in Africa is conflict. The UN estimates that 18 million people in Africa are displaced out of which 12.5 million are internally displaced persons. By losing access to their land, people are unable to produce crops for consumption. Displacements also destroy incomes and associated purchasing power so that families rely on humanitarian aid for staple food. However, dangers of war and terrorism prevent aid organizations from accessing those most in need. The security map below shows regions affected by conflict. Islamist militants pose a threat in north-east Nigeria (Boko Haram), Mali/Burkina Faso/Niger (Islamic State affiliates), northern Mozambique (Islamic State affiliates) and Somalia (Al-Shabab). Ethnic conflict in DRC, South Sudan and Ethiopia causes security risks in those countries.

Locusts

Another driver of food insecurity in 2020 is the ongoing desert locust infestation in East Africa. The locusts are causing large-scale crop damage as 1 km2 swarms can eat the same amount of food as 3500 people in one day. This has pushed around 20 million people in Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan into acute food insecurity according to the FAO. Areas particularly affected are southern, eastern, and central Ethiopia; northern and central Somalia; northern and central Kenya; northeastern Uganda; southeastern South Sudan. Crop destruction will likely escalate while favorable climatic conditions allow locusts to continue to breed and spread. Furthermore, movement restrictions due to COVID19 cause delays in pesticide freight shipments and hinder locust control operations.

COVID-19

The COVID19 pandemic will likely promote food insecurity through three main channels: declines in household incomes, food price inflation and supply disruptions. Most urban populations in Sub-Saharan Africa earn income in the informal economy and the service sector and have extremely low savings. These populations are particularly at risk of losing their income sources due to the closures of markets and movement restrictions. The COVID19 lockdowns will also lead to a decline in seasonal labour. Moreover, remittance payments are projected to drop by about 20% due to the slowdown in global economic activity. This all results in a significant reduction in people's purchasing power.

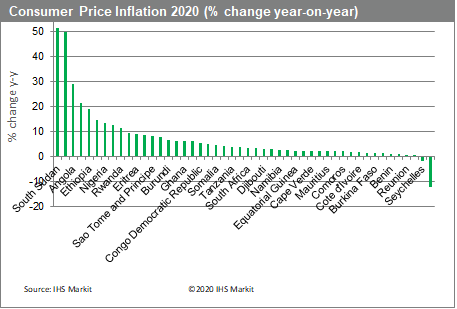

Despite lower core inflationary pressures stemming from low oil prices, food price inflationary pressures will be elevated pushing annual headline inflation up as less farmland under cultivation, protectionist policies and restricted access to markets will result in good price increases. IHS Markit predicts consumer price inflation in almost all of Sub-Saharan Africa. Consumer prices in large economies such as Angola, Ethiopia and Nigeria are expected to increase by more than 10% y-y in 2020. Depreciating currencies in countries such as South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Kenya will also contribute to food price increases for the local population. Finally, supply chain disruptions will limit access to food especially in remote areas and may contribute to price increases. If access to seeds and agricultural inputs remains disrupted due to movement restrictions, sufficient food availability in the second half of the year is at risk.

Posted 12 May 2020 by Marie Lechler, Director, Trade and Supply Chain Product Management, S&P Global