S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

10 Mar, 2025

By Nushin Huq

| A rendering of Applied Digital's Source: Applied Digital Corp. |

As artificial intelligence drives the need for more electricity, owners and operators of smaller, leased datacenter facilities are under pressure to find new ways to manage the financial risks that come with huge capital investments.

The scale of generation needed to fulfill future demand from artificial intelligence, bitcoin mining or cloud services is still difficult to pin down, and utilities do not want to be left with stranded assets. As a result, datacenters operators are increasingly being required to pay for new facilities and sometimes even their power supply upfront, a particular challenge for smaller companies.

"They are extremely large power users and could potentially place residual costs on traditional customers if they only have short-term agreements without adequate protections," Darcy Neigum, vice president of energy supply at MDU Resources Group Inc. subsidiary Montana-Dakota Utilities Co., told Platts, a part of S&P Global Commodities Insight. "Many datacenter loads are also very price sensitive and are shopping around between utilities to try and find the best rate and potentially overinflating the number of actual data loads expected to hook up to the grid."

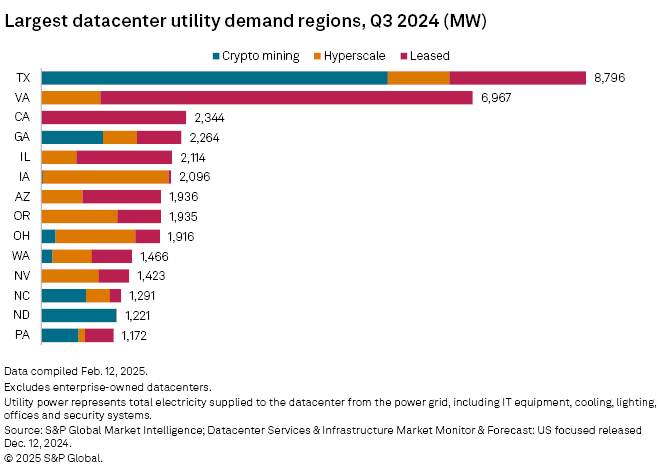

Applied Digital Corp., with a datacenter in Ellendale, North Dakota, is an MDU customer and has a multiyear power supply contract with the utility. That datacenter currently requires 180 MW — more than one-fourth of MDU's generation portfolio — and has the Midcontinent ISO's approval to increase its total demand to 530 MW. Construction is underway to expand the facility by the end of 2025. The company first focused on bitcoin mining before transitioning into artificial intelligence in 2022. AI added a new market and gave Applied Digital more flexibility in siting its facility; it did not need to be in a traditional load center.

Regulators are scrutinizing utility deals with datacenters to make sure that other ratepayers are not left with that liability, Etienne Snyman, Applied Digital's vice president for power, told Platts. Hyperscalers such as Amazon.com Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Google LLC have huge balance sheets that allow them to more easily manage those risks, Snyman added.

"There are challenges that the non-hyperscaler companies have to work through, which is finance securities or credit," Snyman said. "The solution to manage that is to work with the tenants on providing that security or credit through either guarantees or letters of credit or the likes, which for the hyperscalers, given their credit ratings and market caps, is certainly easier."

Applied Digital was not able to disclose specifics on how it was able to work with potential tenants to address financing challenges. On Feb. 12, the company announced it closed a $375 million financing deal with Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank Ltd., a portion of which it will use to develop the Ellendale campus. That followed a January announcement that Macquarie Asset Management Pty Ltd. would invest $5 billion in Applied Digital's datacenter pipeline, including $900 million to build out the Ellendale facility to 400 MW.

Applied Digital's expanded datacenter will take advantage of congestion within the MISO footprint caused by wind generation. The company was able to select a location with abundant land and available power supply, and no new generation was needed for the project. Existing wind farms were incurring significant curtailments to manage grid congestion, Snyman said, and as the datacenter adds load, it can absorb that wind energy output.

"And when you're starting with a clean slate like that, you don't necessarily have to follow the rules of the previous developments," Snyman said. "You can look at, where does it make the most sense to generate that amount of electricity, and look at energy-rich locations where they are blessed with natural resources that could be solar, wind or natural gas."

DC BLOX Inc., a retail colocation datacenter company, also builds hyperscale-ready sites, which is similar to colocation retail but with the intention to lease to a single hyperscaler. The company has two hyperscale-ready facilities in the suburbs of Atlanta. DC Blox worked with Southern Co. subsidiary Georgia Power Co. and GreyStone Power Corp., an electric cooperative serving eight counties west of Atlanta, as well as Duke Energy Corp. in South Carolina. The company focuses on the US Southeast due to changing dynamics of power procurement.

"We saw the transition coming down in the Southeast, particularly in the Atlanta area. We're following the leaders now; they are telling us where they want to go," Bill Thomson, vice president of marketing and project management at DC Blox, told Platts. DC Blox is developing a facility east of Atlanta with up to 120 MW of capacity. In fall 2024, it announced three "edge node" sites, two in Alabama and one in South Carolina, each starting at 5 MW.

Southern Co. spokesperson John Kraft said that between 2022 and 2025, approximately 80% of the company's estimated increase in power need is from new datacenter commitments.

In January, Georgia regulators amended existing rules for large-load customers, defined as those using more than 100 MW, that include minimum billing requirements and longer contract term lengths. Those changes will not affect DC Blox because the company already had agreements with Georgia Power and GreyStone Power in place, Thomson said.

"The new rules and regulations approved by the [Georgia Public Service Commission] are part of the constructive regulatory environment in Georgia, which further protects customers and helps ensure that growth benefits all customers as we plan and meet the needs of new large-load customers coming to our state," Kraft said.

The biggest challenge companies like DC Blox face is the changing upfront requirements, Thomson said. Regulators are concerned about stranded capacity in the future and are alleviating that risk with more upfront payments. Those costs led the company to pause its plan in South Carolina.

"I would say competition for power is significant," Thomson said. "It's causing upfront investment risk to increase. That, at least for an independent provider like us, it's impacting our ability to deliver."

In addition to upfront equipment costs, such as substations and transmission lines, utilities are also asking for guaranteed power use by a certain date.

"We have to start paying these utilities a certain amount of usage and rates on a given date," Thomson said. "That's too much risk for our financiers to take on."

The process can put companies in a bind, Thomson said. Hyperscale customers will not come to the table unless they have guaranteed power by a certain date. Power companies want signed contracts.

"We have to make the upfront infrastructure commitments or power usage commitments before having a contract," Thomas said. "There's this dynamic going on, the utilities are trying to protect themselves."

Like Snyman, Thomson said that ultimately, investors are looking at tenants' credit, which is not a problem for hyperscaler tenants but may be impossible for small AI startups.

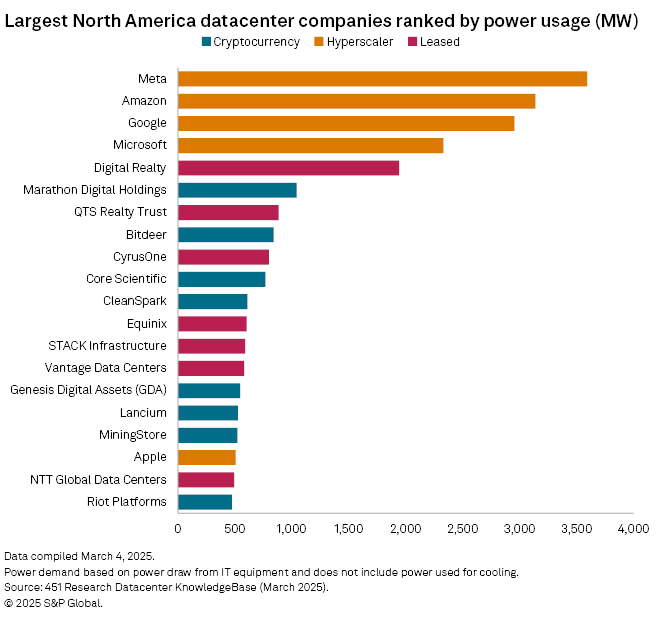

"If you are a datacenter provider who's planning on having 280 MW, you have to essentially reserve that and start paying for it and pay for the infrastructure to get it there," said Kelly Morgan, research director at S&P Global Market Intelligence 451 Research. "That is doable and probably almost normal for Microsoft or an Amazon building out a big campus. For most of the smaller providers, that is pretty much undoable."

The largest datacenter companies can also get creative, Morgan said. They can build a datacenter, lease it out to a hyperscaler with a long-term contract, sell that datacenter to an investor such as a property fund, and then reinvest that money for the next project. For datacenter companies that do not have one hyperscale tenant with a long-term contract but multiple tenants with contracts of varying lengths, that will be much more difficult.

"It may just end up dividing even more the scale players from the other players, which has already made a big difference," Morgan said.